CLIMATE & ENVIRONMENT

‘Unprecedented killing’: The deadliest season for Yellowstone’s wolves

On the 150th anniversary of America’s first national park, one-third of its wolves are dead

By Joshua Partlow

March 4, 2022 at 6:30 a.m. EST

An animal carcass, lower right, lays sprawled on the ground near Jardine, Mont., on Feb. 7. (Photos by Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

GARDINER, Mont. — Kim Bean saw the black ravens clustered in the leafless cottonwoods and thought: There’s our death.

The carcass had been on the hillside overlooking Yellowstone National Park for some time, but there was still enough flesh to attract scavengers. Bean crouched over it, examining the thin bones on the snowy ground.

“They chopped off the feet,” she said.

The head was also gone, making it harder to identify the animal. But there were clues. The radius and ulna were not fused, ruling out the mule deer or elk that migrate out of the park in winter across the plateau known as Deckard Flats. Bean suspected it was a gray wolf, and she had plenty of reasons to think so.

In less than six months, hunters have shot and trapped 25 of Yellowstone’s wolves — a record for one season — the majority killed in this part of Montana just over the park border. The hunting has eliminated about one-fifth of the park’s wolves, the most serious threat yet to a population that has been observed by tourists and studied by scientists more intensively than any in the world.

Since 1995, when staff released wolves into Yellowstone — where they had been wiped out decades before — this celebrated experiment in wildlife recovery has become a defining feature of America’s first national park, now celebrating its 150th anniversary.

Each step of their comeback has been documented in books, movies and daily reports from the field by a passionate band of wildlife watchers. Bean, who helps lead the nonprofit group Wolves of the Rockies, is one of those enthralled with wolves and their stories. And she has watched in horror as the body count has mounted.

“This is a definite war,” she said.

‘Take wolves out through any means possible’

Elk graze in Gardiner, Mont., a gateway town into Yellowstone National Park, on Feb. 5. Gardiner is the town closest to wildlife management unit 313, where many wolves have been harvested on the park's northern border this year. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Afederal judge’s ruling last month that overturned a Trump administration policy and restored federal protections to gray wolves across much of the United States does not apply to wolves in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming. It is in these Republican-led states where most of the wolf hunting — and the most intense fights over wolf management — is playing out.

The Interior Department is reviewing whether to put the gray wolves of the Northern Rocky Mountains back on the endangered species list. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland recently warned Montana officials that their actions “jeopardize the decades of federal and state partnerships that successfully recovered gray wolves in the northern Rockies.”

The management of Montana’s wolves passed to the state a decade ago. Since that time, it has sharply restricted hunting around Yellowstone — until last year.

Hounds chased a Yellowstone mountain lion into a tree. Then Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte (R) shot it.

The Republican-controlled legislature passed laws mandating a decrease in the state’s wolf numbers and allowing hunters to catch wolves in neck snares, hunt them at night and lure them with bait. Then in August, the state fish and wildlife commission eliminated rules that only one wolf could be killed per year in each of the two hunting districts bordering Yellowstone.

Cam Sholly is the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

The result has been “four to five months of basically gloves-off, take wolves out through any means possible,” Yellowstone Superintendent Cam Sholly said in an interview. “It is highly concerning to us.”

The culling has also divided neighbors and relatives who live at the park’s edge. Dozens of businesses that depend on tourism and wildlife viewing argue that these wolves are worth more alive than dead. Wolf hunters have celebrated their kills on social media, and they defend their actions as legal and just.

And each day at sunrise, both sides were watching. In pickup trucks and on horseback, hunters “glassed” the hillsides with binoculars and scopes, checked their traps and listened for howls. Their opponents were out, too, lingering on gravel pullouts on Forest Service roads, their own spotting scopes watching for hunters watching for wolves.

When Bean found the carcass, she texted a photo of it to Carter Niemeyer, a legendary trapper who had been hired by the U.S. government in the 1990s to catch the Canadian wolves that launched Yellowstone’s wolf recovery. It was hard to tell, he told her, but it looked to him like a trophy animal killed and skinned in the field.

Bean read his response aloud: “The reason I say this is the hide was saved along with the head removed and the feet sawed off. This is how an outfitter rough skins a lion, bear, or wolf before taking to taxidermy.”

She bent down and tugged at some soft white hairs that remained near the animal’s tail. She wanted a DNA sample.

“Okay, listen,” she said, straining. “You gave up your life. You can give up your fur. Come on.”

‘It’s sick, is what it is’

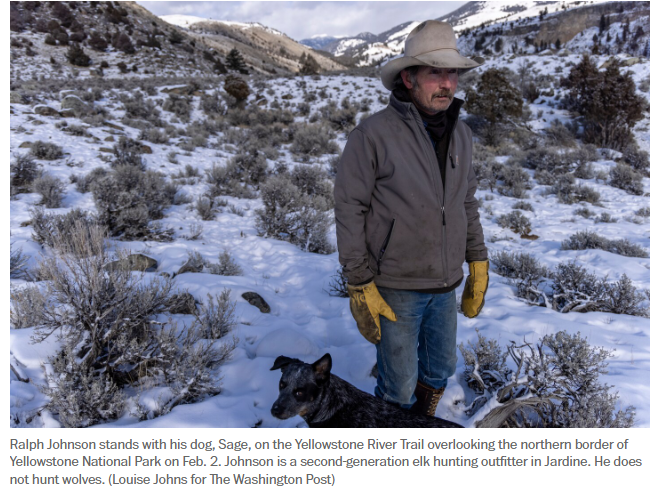

Ralph Johnson stands with his dog, Sage, on the Yellowstone River Trail overlooking the northern border of Yellowstone National Park on Feb. 2. Johnson is a second-generation elk hunting outfitter in Jardine. He does not hunt wolves. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

A cloudy sunrise illuminates Deckard Flats, an area of Forest Service land north of Yellowstone National Park, on Feb. 3. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Nearly every day in winter, Ralph Johnson and his blue heeler, Sage, hike the hills around Deckard Flats. Johnson can look at a trampled patch of ground and distinguish tracks of the coyote from the fox from the cottontail rabbit. He can point out the two ivory teeth in an elk’s skull on the trail — and explain the evidence that a mountain lion brought it down. This place that hunters and wildlife enthusiasts travel the globe to glimpse is, to him, the backyard.

Johnson is a hunting guide. Along with his brother Lloyd, he runs Specimen Creek Outfitters & Adventures, a business started by his father. Winter is normally downtime, staying in shape for long summertime backcountry hunting and horseback riding trips for clients who want to experience a real, if disappearing, Montana. He prefers old-time hunters — Midwesterners who show up in L.L. Bean clothes with wooden-stock rifles — more than the camouflage and assault-weapons crowd. Much of the hunting scene turns him off these days. This winter more than ever.

He has watched hunters regularly gather in groups as large as 20 above Deckard Flats in the late afternoon to scan for wolves, then head out at dawn to shoot them. He has heard them play recordings of howls to lure wolves over the Yellowstone border. Other hunters say dead animals, including elk and horses, are being left out as wolf bait along stretches of park boundary. Johnson hasn’t seen that yet, but it wouldn’t surprise him.

“A person can understand if you want one. One animal of something. Just to respect it, just to have it. But when you start killing like they’re doing, multiple, it’s not even hunting. It’s just killing is all it is. I totally don’t agree with it,” he said. “It’s gross, and it’s sick, is what it is.”

Johnson knows many of the area’s wolf hunters. He doesn’t want to name names or start a feud in the community. But wolf advocates in town say one of them is his brother Warren Johnson, who runs Hell’s A-Roarin’ Outfitters across the creek from Ralph Johnson’s place.

When a reporter approached him in his pickup truck outside his ranch, Warren Johnson didn’t want to talk wolves. “I’ve been into it too many times,” he said. “That’s it.”

Their clients don’t set out to kill wolves, his wife, Susan, responded by email, but “we just let our elk hunters shoot one if the season is open and they have a license!”

“We definitely know they need to be shot to keep their numbers in check,” she said.

She mentioned another local outfitter whose clients shot three wolves this fall from “a pack of 27!!!!!”

“Way too many!”

A home near Emigrant, Mont., is decorated with gray wolf pelts. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Anti-wolf fervor has been around as long as humans have shared land with wolves. But it has flourished in the West in an era of increasing political polarization. Wyoming permits unlimited wolf hunting across 85 percent of its state. Idaho Gov. Brad Little (R) last year signed a bill that allows killing as much as 90 percent of the state’s wolves.

There is a stick-it-to-liberals flavor to this debate. Around Yellowstone, visiting hunters have heard others bragging about wolf kills. On the Facebook page of one local guide, the O Bar Lazy E Outfitters, are several pictures of slain wolves, including one image where two dead wolves flank a Trump-Pence 2020 campaign sign.

“We saved a few elk today,” read the October 2020 caption.

Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte (R) himself killed a Yellowstone wolf last year that was wearing a research collar and had strayed from the park. In December, he killed a mountain lion that was also being tracked by Park Service biologists. In shooting the wolf, the governor violated a state hunting rule because he failed to take a required trapper certification course, and was given a written warning. He later said he “made a mistake.”

Gianforte’s office did not respond to a request for comment about wolves; his spokeswoman defended his lion hunt as legal.

In December, Sholly, the Yellowstone superintendent, wrote to Gianforte asking him to suspend wolf-hunting in the two districts north of the park because of the “extraordinary” number of dead wolves. The past quotas in those areas had not only protected wildlife, he wrote, but also the economic and tourism interests of the state. Yellowstone hosted nearly 5 million people last year, the most in its history. Tourism generates $640 million annually and thousands of jobs; wolf viewing alone accounts for $30 million to $60 million per year, according to peer-reviewed studies.

“Once a wolf exits the park and enters lands in the State of Montana, it may be harvested pursuant to regulations established” by the state fish and wildlife commission, Gianforte replied last month. “These regulations provide strong protections to prevent overharvest.”

To Sholly’s mind, two main arguments against wolves — that they prey on livestock and threaten elk — are not convincing here. A wolf has killed livestock only once in the past three years in the county that encompasses the hunting districts near the park. And elk numbers, locally and across Montana, meet or surpass objectives set by the state.

“If we’re not accomplishing a conservation objective, and we’re hurting the economies, I’m not sure what we’re doing,” Sholly said in an interview.

The commission held an online meeting in late January to address the rising wolf death toll in southwestern Montana. Six of the seven commissioners had been appointed by Gianforte; three of the commissioners had animals mounted on the walls behind them.

When the public got to speak, people from across the country made impassioned pleas on behalf of wolves and Yellowstone.

“Yellowstone was created to protect wildlife,” Stephen Capra of the organization Footloose Montana told the commission. “What we’re doing is criminal around the park. It’s a disgrace to the nation.”

In a Wisconsin, a wolf hunt blew past its kill quota in 63 hours

The commission voted to stop hunting in the broader southwest Montana region that included the Yellowstone-adjacent districts once 82 wolves had been hunted. At that time, the body count stood at 76. For the moment, hunting around Yellowstone would continue.

Sholly had gone to high school in the small town of Gardiner, just north of the park, and his dad had been chief ranger at Yellowstone. He knew the charged politics of the issue and was familiar with the local hunters. He could only wait and hope that the remaining six wolves wouldn’t come from the park.

“This is a very small number of people that are killing these wolves,” he said.

Share this article

Share

‘Hard to see all the change’

Bill Hoppe looks out the door of his barn on his ranch in Jardine, Mont., on Feb. 4. Hoppe relocated his multigenerational outfitting business 150 miles north soon after the wolves were reintroduced because he said the wolves decimated the elk herds he used to hunt. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

A photo of Bill Hoppe's grandfather, Paul Hoppe, with a string of pack horses in Yellowstone National Park. He was hired by the Park Service to herd buffalo and shoot the remaining wolves in Yellowstone in 1926. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Every morning, Bill Hoppe leaves his house to hunt wolves. But at 69 years old, he is engaging in more of a daily ritual than determined stalking.

“I don’t try very hard. I guard the road,” he said. “Mornings at daylight, you’ll see the eagles coming down the creek out of their roosts, you’ll see elk scattered around, a few deer. I just like to look at everything.”

Hoppe was the nearest neighbor to the carcass Kim Bean discovered. In local wolf circles, his name is often spoken with bitterness. In 2013, he shot and killed a Yellowstone wolf wearing a research tracking collar after wolves had killed more than a dozen of his sheep.

“I never spent such a summer,” he recalled. “Oh, boy. Death threats? Oh, hell, yeah.”

To Hoppe, the debate over wolf-hunting has lost its mind. Wolves need to be managed just as any predator does, he said, and they’re a resilient species that repopulates quickly. The fact that tourists and many locals observe them so intently and know their names — “Old Fluffy or whatever,” as Hoppe says — makes them too emotional.

“I don’t know of anybody around here who’s ever promoted killing all the wolves,” he said. “But, on the other hand, you’ve got all these people who say, ‘Don’t kill any. Let ’em overrun.’ When they get so many, they get diseased.”

A fourth-generation hunting guide whose living room walls are decorated with moose and elk and mountain goat trophies, he made his career taking clients to hunt elk migrating out of Yellowstone and past his house. That herd numbered about 20,000 before wolves were reintroduced and has declined substantially, partly because of wolves but also because of human causes such as climate change and habitat loss.

Elk bunch together on Feb. 2 off Highway 89 in Paradise Valley, Mont., a corridor to the northern entrance of Yellowstone National Park. Elk are a primary food source for wolves. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

“One family I knew had outfitted here for generations, and as the elk herd collapsed, they just kind of moved off and separated and went their own way,” he said. “I saw it break up families that lived here for 100 years.”

The sepia-toned photographs on Hoppe’s living room walls depict a Yellowstone long gone. Back when only a suspension bridge crossed the Yellowstone River, not a paved road jammed with tourists. Back when his grandfather was hired to help eradicate wolves in the 1920s as official park policy.

Wolf hunting connects him to a vanishing past, before tech money moved in and the government micromanaged his backyard.

“It’s hard to see all the change, is all.”

Hoppe said he wants people to be “reasonable.” If the federal government tries to put wolves back on the endangered species list, he said, the consequences for the wolves could be worse.

“This perception that they’re all going to disappear and we’re going to murder ’em all? There’s no way to get rid of them, short of poison,” he said. “And if these people keep pushing and pushing and keep taking away and keep taking away, that’s what will happen.”

“Don’t try to take it all from us,” Hoppe warned. “Because this is Montana. This is not Yellowstone Park.”

‘Best wildlife viewing situation in the world’

Wolf watchers in Yellowstone National Park use spotting scopes on Feb. 5 to gaze at wolves about two miles away. The wolves are from the Junction Butte pack, which has been heavily harvested this hunting season. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Joe Kaul counts the wolves from the Junction Butte pack that he sees in Yellowstone National Park on Feb. 5, 2022. Kaul, from Livingston, Mont., took six weeks off work so he could watch wolves. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Inside Yellowstone, the wolf-watchers’ cars were double- and triple-parked on a snow-covered pullout overlooking the drainage area of Hellroaring Creek. They had clustered their tripods together like cameramen at a news conference, their eyes pressed to their Swarovski spotting scopes.

“There’s a huge bunch. Holy cow!” said Reve Carberry, who lives in a motor home outside the park to devote himself to the daily pursuit of observing wolves. “There’s about seven or eight over in a line.”

“Rick just said 10,” added Jeff Reed, a lodge owner who stood next to him.

“That’s probably the correct number, then,” Carberry conceded.

Rick McIntyre stands at the upper Hellroaring Creek pullout, a common area for watching wolves, on Feb. 5. Since 1995, McIntyre says, he has barely missed a day of wolf watching. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

Rick McIntyre is rarely wrong about wolves. The former Park Service employee is a legendary figure in Yellowstone who has observed and chronicled the predators on a daily basis for nearly three decades. With his courtly demeanor and soothing voice, he’s chief historian for the most famous wolf population in the world.

He has written three books on wolves — with a fourth forthcoming — and has compiled more than 12,000 pages of single-spaced notes from his daily observations. He can tell stories from memory about individual wolves and their family histories, their acts of heroism and betrayal, their hunting prowess and empathy for the wounded or outmatched.

The wolves lounging on a rocky hillside about two miles across the valley from McIntyre and the others were members of the Junction Butte pack. Starting last spring, McIntyre observed that pack for 184 days in a row. Their den was visible from the road, and hundreds of tourists gathered alongside him each morning to watch the pups as they tumbled and scampered in the grass.

“It certainly was, at that time, the best wildlife viewing situation in the world,” he said. “For anyone, regardless of their age or physical abilities, could drive to that spot in Yellowstone, with binoculars or a spotting scope, and see a mother wolf nursing and caring for her pups.”

When the September hunting season started, two of the Junction Butte pups and a yearling were shot dead. In subsequent weeks, five more of their relatives were killed.

Doug Smith, a Yellowstone wolf biologist, holds a wolf pelt and skull used for research. Smith was part of the team that reintroduced wolves to Yellowstone in 1995. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

“Virtually every time they go out of the park, they lose wolves,” said Doug Smith, the park’s senior wildlife biologist who has led Yellowstone’s wolf restoration project since its inception in 1995. “They’re going out for a day or two, and then they come in for weeks. I sit here with my fingers crossed: Please don’t leave the park.”

Hunters have killed off one entire pack — the Phantom Lake pack — as well as Brindle, the alpha female of the 8 Mile pack, known for her distinctive salt-and-pepper coat, shortly before breeding season, putting that pack’s reproduction at risk. Smith estimated that there were 125 to 130 wolves in Yellowstone when the hunting season started and 89 now.

That is not a rough guess. His staff monitors their movements using radio telemetry and GPS tracking collars — applied by darting them with tranquilizers — along with regular airplane flights and remote cameras. They know how many wolves are in each of the park’s remaining eight packs, along with their age, sex, color and hierarchical position.

The decades-long research project Smith oversees charts one of the most successful ecosystem recovery efforts in the United States. It has informed wildlife management around the world, showing how apex predators shape their environment; how, for example, overgrazed willows, aspens and cottonwoods rebounded when wolves began thinning the elk and bison herds.

After a particularly costly wolf hunt in 2012, some of Smith’s donors said he could no longer characterize the park’s wolves as being in a natural, unexploited state.

“We got through that, with just 12 killed. Now we’re at 24,” he said in an interview in February, before another wolf was killed. “We were doing some of the best science on one of the few unexploited wolf populations in North America. We can’t make that claim anymore.”

“The two primary objectives of the National Park Service are nature preservation and visitor enjoyment,” he added. “And both of these things are impacted by this unprecedented killing.”

Cara McGary, who runs In Our Nature Guiding Services, and Reed, the owner of Reedfly Farm on the Yellowstone River, recently formed the Wild Livelihoods coalition to represent businesses whose interests are threatened by such an aggressive wolf hunt.

The wildlife viewing trips led by McGary, a biologist who has worked in Antarctica and Australia before moving to Gardiner, can cost $700 per day. And viewing a Yellowstone wolf is a primary draw for her clients. The impact on her business this winter is already noticeable, she said.

“More days are happening when people are not seeing wolves at all,” she said.

error

An error occurred. Please try again later.

(Video: TWP)

‘This is how they get killed’

On the same day Bean found the carcass, McGary received a text from a friend.

“Wolves howling audible from our place rt now. This is how they get killed..." she read. “Trucks racing up the rd...”

McGary drove up the hill and met Bean as she was heading down. They conferred about the carcass and both suspected wolf. Bean later realized she didn’t have enough fur for DNA testing, and she wanted a quicker answer. She returned and picked up the animal’s leg and put it in her car.

“It was a wolf,” she said.

Bean said the confirmation came from a government wildlife official who performs necropsies, but she declined to name her contact.

This episode reference doesn't exist. It may be not be live yet.

As it happened, the last six wolves killed in southwestern Montana this year came from places other than Yellowstone. The state closed the region for wolf-hunting on Feb. 17, after harvesting 82. Bean doesn’t know whether the one she found had already been reported to the state. Or whether it had been poached. Both hunters and wolf-lovers believe that more wolves get killed than make the official tally.

When she had first seen the carcass, her mind raced. Who is this?

“Is this one of my Junction Buttes? Is this one of my 8 Miles?” she recalled. “It’s immediately just that feeling of — a family lost.”

As she stood over the bones, the mountainside resounded with a ghostly keening: the howling of wolves.

A wolf carcass near Deckard Flats in Jardine, Mont., on Feb. 7. It is common for hunters to skin the wolf, take the pelt and cut off and the head and feet to make a trophy. (Louise Johns for The Washington Post)

About this story

Editing by Juliet Eilperin. Photo editing by Olivier Laurent. Design editing by Madison Walls. Copy editing by Susan Stanford. Audio production by Robin Amer. Mixing by Sean Carter. Video editing by Luis Velarde.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/03/04/yellowstone-wolves-hunting/

'news > 과학 science' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Albatrosses 알바트로스. 새. 인간과 새. 새 새끼 몸무게를 측정하는데, 어미 알바트로스가 인간을 의사 대하듯이. (0) | 2024.02.06 |

|---|---|

| 인간과 다른 영장류 수면 시간 (잠자는 시간) 비교. 인간 7시간, 다른 영장류 9~15시간. 야행성 동물들이 주간활동 동물보다 더 많이 잔다. (1) | 2024.02.06 |

| 늑대를 죽여서는 안되는 이유. 늑대의 역할. 옐로우스톤 늑대 재도입 영향력 논쟁 (0) | 2024.01.15 |

| 세상에서 제일 적은 고양이 - 붉은점박이삵 (rusty spotted cat) (1) | 2024.01.15 |

| 용은 어디서 왔는가? 용의 출처. 해룡, 해마의 임신, 수컷이 알을 품고 다닌다. Seahorses, Sedragons (0) | 2024.01.01 |

| 캐나다 유콘 야생 동물. 스라소니 (lynx 링스) , 코요테, 가문비 멧닭 (0) | 2023.11.29 |

| 동아시아 느티나무 역할. 해외에 수출되는 느티나무 (0) | 2023.08.01 |