옐로우스톤 늑대 재도입이 미친 영향에 대한 토론과 논쟁. 논쟁 주제는 늑대 재도입으로 인해, 옐로우스톤의 식물군, 버드나무, 미루나무, 사시나무 등이 번성하게 되었는가 ?

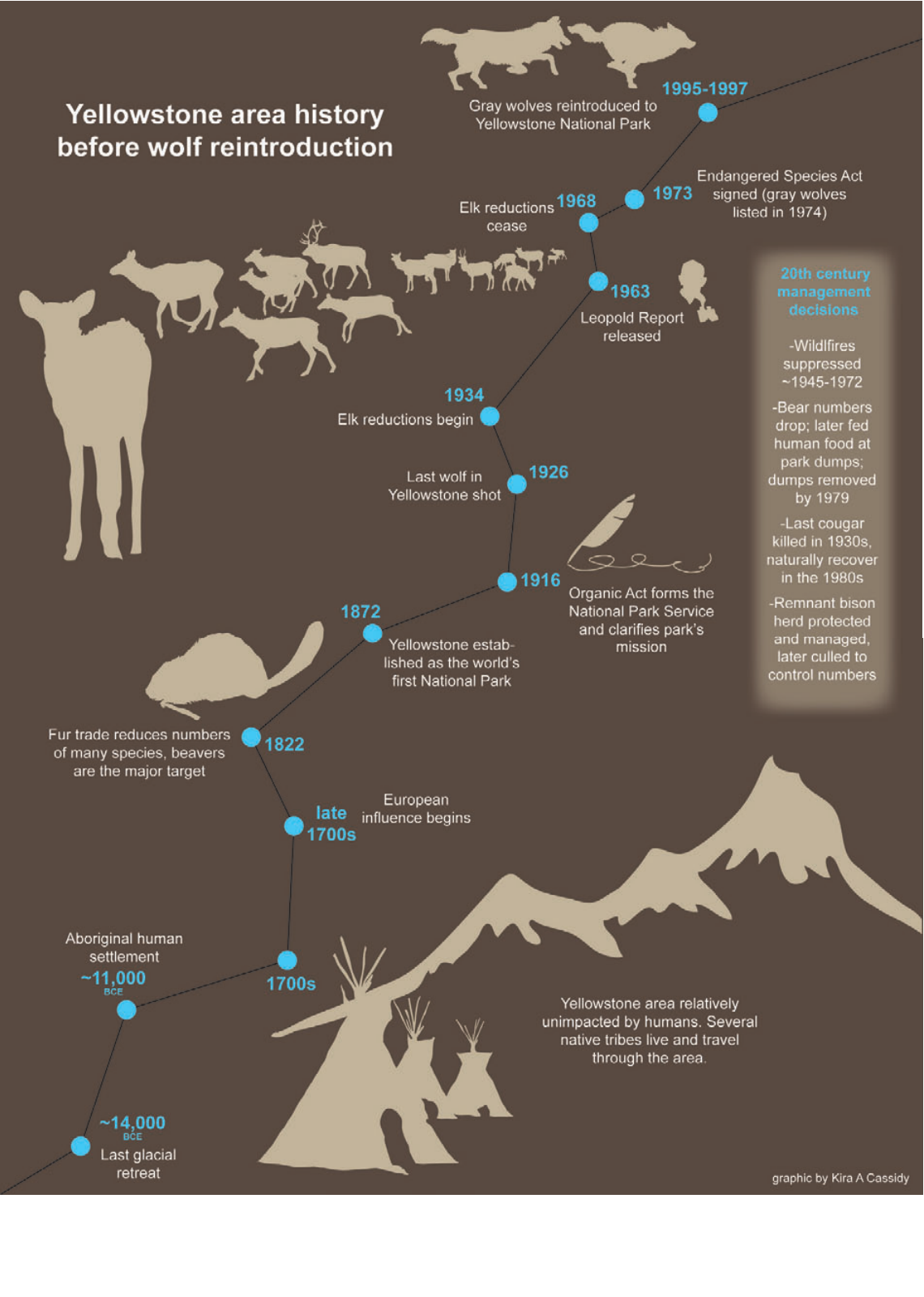

1995년 미국 엘로우스톤 자연국립공원에 70년만에 다시 늑대가 되돌아왔다. 캐나다 알버타 주 늑대 14마리를 엘로우스톤에 재도입해 살게 했다. 96년에 17마리를 더 도입했다.

마크 보이스 (Mark Boyce) 생물학자 관찰 보고. 늑대 재도입 이후 변화. 사슴과 북미산 bison 의 숫자 변화. 사슴들이 뜯어먹었던 버드나무, 미루나무, 사시나무 등과 같은 나무들이 복원되었다.

1926년 엘로우스톤에서 사냥꾼들이 마지막 남은 늑대를 사살했다. 늑대가 사라지니, 사슴 숫자가 급격히 늘어났다. 1995년 늑대가 재도입된 이후, 사슴 숫자가 2만 마리에서 8천마리로 감소했다. 1만 2천 마리가 줄었다는 의미다.

사슴 숫자가 너무 늘어나버려, 겨울에는 먹이를 구하지 못한 사슴들이 수천마리씩 아사했다고 함.

그 이후 엘로우스톤 관리자와 생물학자들이 늑대를 다시 데려와, 자연적으로 사슴 숫자들을 조절할 수 있도록 했다.

사슴 숫자가 많을 때는 2만 마리였으나, 지금은 7800마리 정도 유지하고 있음.

사슴 숫자 감소 원인들 1) 늑대 재도입 이후, 늑대가 사슴 사냥 2) 나쁜 날씨 탓, 3) 사슴 사냥 허용 4) 그르즐리 곰들이 사슴 새끼 사냥 증가

식물군의 변화 초래. 그 이유는 사슴들 개체 숫자가 줄어드니, 풀, 나무들이 더 무성하게 자라날 수 있게 됨.

늑대 재도입으로 사람들이 엘로우스톤에 덜 개입함으로써, 자연적 생태계가 작동하게 되다.

언론보도.

Edmonton

How 31 Alberta wolves changed the natural balance of Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone has benefited 'in ways that we did not anticipate,' says U of A researcher

CBC News · Posted: Oct 21, 2018 9:00 AM EDT | Last Updated: October 21, 2018

Jan. 20: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is pondering lifting protections for transplanted Canadian grey wolves after a recovery experiment for the endangered species has proven too successful. (MacNeil Lyons/National Park Service)

An eco-experiment that started with 14 Alberta wolves has shown just how powerful the laws of nature really are, says a University of Alberta ecologist.

In 1995, the wolves were introduced to Yellowstone National Park, almost 70 years after the last wolf in the park's original pack had been shot as part of a systematic program to get rid of them.

Another 17 wolves were released into the park one year later. And since then, the changes within the park have been nothing short of remarkable.

How O-Six became Yellowstone's 'most beloved' wolf

"They certainly have been able to restore the natural ecological processes that prevailed in the park prior to the extirpation of wolves," Mark Boyce, a U of A biological science professor, told CBC's Radio Active.

"And it's been dramatic."

Boyce has spent 40 years researching large mammals in Yellowstone, the oldest and one of the largest national parks in the U.S. This month, his paper on the rebirth of Yellowstone's flora and fauna was published in the Journal of Mammalogy.

Reintroducing wolves has changed Yellowstone's elk and bison populations, and has sparked the recovery of several tree species, including willow, cottonwood and aspen.

Original wolf pack systematically wiped out

To appreciate the domino effect on Yellowstone's ecosystem, you must first understand what happened in the past, said Boyce.

In 1926, the last Yellowstone wolf was shot, the culmination of a deliberate effort to get rid of the predators. The immediate result was that the park's elk population exploded.

"Within about 15 years the park decided they had to cull the elk to keep things in check," said Boyce.

A herd of elk graze in the meadows of Yellowstone National Park in 1997. Since the introduction of Alberta wolves in 1995, the park's elk population has dropped from 20,000 to less than 8,000. (The Associated Press)

Thousands of elk were killed each year until 1967, when political pressure grew to stop the annual hunt and begin a period of a natural regulation to see what would happen, he said.

"So the number of elk increased and increased, and every time they'd have a tough winter they'd have thousands dead elk on the northern range. And so the park recognized that they had to do something."

Enter the Alberta grey wolves.

The park's wolf population has been sitting at about 100 for the last decade. The elk population has dropped from a high of 20,000 to a current level of about 7,800 animals, Boyce said.

A combination of things happened around the time the wolves were relocated to immediately bring down the elk population, he said, including a bad winter, a heavy elk hunt and an upswing in grizzly bears preying on elk calves.

Fewer grazing elk means flora has come back

Things are still changing, he said.

Much of the elk herd has taken to leaving the park over winter, with only about 1,500 in the park's northern range. That has left room for the bison population to take over as the park's dominant herbivore.

"And bison numbers have been increasing, every year since wolf reintroduction. And now there are in the neighbourhood of 5,000 bison on the northern range."

Exercise during pregnancy can reduce risk of major complications, U of A-led research finds

With elk numbers down, the animals are not eating as much of the vegetation, allowing willow, cottonwood and aspen trees to flourish, he said. Grazing elk had eaten many trees down to the ground.

"Yellowstone has benefited from the reintroduction of wolves in ways that we did not anticipate," Boyce said in a news release.

"We would have never seen these responses if the park hadn't followed an ecological-process management paradigm — allowing natural ecological processes to take place with minimal human intervention."

DID WOLVES REALLY START A TROPHIC CASCADE IN YELLOWSTONE?

JORDAN SILLARS

Jul 15, 2021

You’ve seen the video.

Narrated by British environmental activist George Monbiot, “How Wolves Change Rivers” tells the incredible story of how gray wolves sparked a cascading series of ecological benefits for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

“We all know that wolves kill various species of animals,” Monbiot begins. “But perhaps we’re slightly less aware that they give life to many others.”

Prior to wolf reintroduction in 1995, Monbiot explains, increasing elk herds overgrazed the riparian areas around Yellowstone’s rivers and streams, which led to erosion, habitat loss, and difficulty for the area’s animals and plants. Then, when wolves entered the landscape, they pushed the herds away from those rivers and streams, allowing the plants and trees to recover and restoring the area’s natural biodiversity.

If this sounds compelling, you’re not alone. The video has racked up over 43 million views as of this writing, and nearly as many (seemingly) articles and papers have been published highlighting Yellowstone’s “trophic cascade” catalyzed by increasing wolf packs.

There’s just one problem: It’s not entirely true. Elk herds did decline following wolf reintroduction, and those declines have spurred ecological benefits for the region (though even this is up for debate). But many biologists hold that wolves can’t be credited with Yellowstone’s recovery. A host of complex and interlocking factors have led to a rebound for some animal and plant species in the GYE, and wolves are only one small part of that story.

What is a Trophic Cascade?

영양 폭포 (trophic cascade) -

The term “trophic cascade” refers to how animals at the top of a food chain affect plants and animals farther down the line. Trophic cascades have been well-documented among food chains involving spiders, fish, insects, and snails that exist in relatively small spaces such as lakes.

In the early 2000s, just a few years after wolves were reintroduced in Yellowstone, scientists began asking the question: Could wolves catalyze a trophic cascade and bring ecological benefits to the region?

The idea isn’t entirely unfounded. Researcher Mark Hebblewhite documented such a cascade in Canada’s Banff National Park in a paper published in 2005. Another scientist, David Mech, who counts himself among the skeptics of a trophic cascade in Yellowstone, called Hebblewhite's study “the only one that has provided seemingly irrefutable evidence of a true trophic cascade from wolves through prey, vegetation and song birds.”

Since then, scientists have credited gray wolves with bringing back everything from willow trees to songbirds to insects. As in the video above, wolves have also been credited with halting erosion around rivers by encouraging beaver habitat and keeping ungulates off the riverbanks.

Wolves accomplish this miraculous feat, according to a 2004 study by William Ripple and Robert Beschta, by preying on elk herds and creating a “landscape of fear” that discourages these cervids from over-browsing plants and trees around Yellowstone’s rivers.

“Can predation risk structure ecosystems? Our answer—based on theory involving trophic cascades, predation risk, and optimal foraging, in addition to a developing body of empirical research—is yes,” the authors conclude.

Further studies were published since the early 2000s, and media outlets and pro-wolf activists gravitated to the narrative. If wolves are the primary drivers of the resurgence of biodiversity in Yellowstone, the trophic cascade theory provided a simple, accessible scientific framework within which to argue for the increased wolf presence on the landscape.

Correlation vs. Causation

There’s no question that cervid herds have declined in Yellowstone since wolves were reintroduced in 1995. But to blame (or credit, depending on your perspective) wolves with that decline is more difficult than it sounds. It isn’t enough to point out that wolf packs increased at the same time herd sizes decreased; scientists must prove that wolves caused the herd decreases.

Researcher Benjamin Allen and his colleagues argue in a 2017 paper that many trophic cascade studies fail because they cannot prove this causal connection.

“The fallacies lie in coming to a conclusion based on the order or pattern of events, rather than accounting for other factors that might rule out a proposed connection,” they say. “Unfortunately, but perhaps motivated by the dire status of many carnivore populations, a growing number of studies rely on weak inference when valuing the roles of large carnivores in ecosystems.”

As for those first trophic cascade papers in the early 2000s, Jim Heffelfinger, the wildlife science coordinator for the Arizona Game and Fish Department, says researchers jumped to conclusions based on correlation rather than causation. “They saw some things, and they correlated it with other things without necessarily having the scientific connection between the two,” he said in an interview with MeatEater.

Furthermore, if scientists want to justify the pro-wolf hype, they must also prove that other factors played little or no role in the trophic cascade process. Researchers have pointed out, however, that elk herds are affected by a wide range of factors, including drought, winter severity, human hunting, cougars, coyotes, black bears, and grizzly bears—all of which were factors in the decades after wolf reintroduction.

“In many areas, bears are important contributors to limiting ungulate numbers,” Mech said. “Ferreting out the role of each of these factors in the [Yellowstone National Park] elk decline is a complex task that has yet to be accomplished.”

By limiting elk herds, wolves were also credited with restoring beavers by giving them larger, healthier trees to use in their dams. But this phenomenon may have a much simpler explanation: between 1986 and 1999, Mech reports, biologists released 129 beavers on the Gallatin National Forest in seven drainages just north of the Yellowstone boundary. (Ironically, wolves have more recently been accused of killing too many beavers in another national park in Minnesota, which has “altered the very landscape” of the park.)

While it’s no doubt true that wolves played a role in lowering elk numbers, no one has been able to quantify that role.

“Wolves contributed to that decline in elk, but wolves didn’t cause that decline in elk,” Heffelfinger said. “They were just part of it, and nobody knows what percent. It’s almost impossible to sort that out. People who are lifelong Yellowstone wolf researchers haven’t been able to figure it out.”

Landscape of Fear?

Even if wolves haven’t singlehandedly decimated elk herds, trophic cascade proponents argue that they have contributed to a “landscape of fear” that keeps cervids away from Yellowstone’s rivers.

There may be some evidence for this in certain circumstances. According to a 2010 paper by John Laundre and his colleagues, two separate studies in the early 2000s documented elk shifting towards forest edges in response to predation by wolves. We also covered a recent study that found mountain lion numbers are dwindling in part because wolves are pushing elk into areas that are more difficult for lions to hunt.

The question, of course, is whether a landscape of fear (such as it exists) has allowed the aspen, willow, and cottonwood trees to recover in the park. “How Wolves Change Rivers” depicts this recovery as incontrovertible, but most recent studies have cast doubt on even this basic fact.

Mech points out that after Ripple and Beschta published photographs in 2004 documenting willow increase, another set of researchers led by Danielle Bilyeu came along in 2008 and published photos purporting to refute the increase.

Another 2010 study by Matthew Kauffman found that aspen trees hadn’t regrown in Yellowstone even as the elk population declined by 60%.

“Even in areas where wolves killed the most elk, the elk weren’t scared enough to stop eating aspens,” biologist Arthur Middleton wrote in the New York Times in 2014. “Other studies have agreed. In my own research at the University of Wyoming, my colleagues and I closely tracked wolves and elk east of Yellowstone from 2007 to 2010 and found that elk rarely changed their feeding behavior in response to wolves.”

Some researchers have found that the preferred forage of deer is more abundant in areas with longer-term wolf occupancy than in areas with shorter-term occupancy. This may suggest a certain amount of wolf-induced trophic cascade, but it’s no guarantee.

In fact, as biologist Adam Ford noted in a 2015 article, that phenomenon could also be explained in the reverse: “The prediction that the preferred forage of deer is more abundant in areas with longer-term occupancy by wolves is equally valid for a bottom-up driven food web: abundant forage could increase the deer population, thereby stabilizing wolf occupancy.”

Even if scientists acknowledge that certain tree species have made a recovery in Yellowstone, as with beavers, there is another, simpler explanation than a the “landscape of fear” hypothesis. As the work of Thomas Hobbs has shown, water table levels are far more important to willow recovery than the presence or absence of wolves.

Why Hunters Should Care

None of this is to say that wolves have had zero effect on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Heffelfinger acknowledged that some vegetation has recovered in Yellowstone due to declining elk numbers, and wolves have definitely played a role in that phenomenon.

But to overstate the benefits of wolves may well backfire on those who wish to preserve the species.

“Perhaps the greatest risk of this story is a loss of credibility for the scientists and environmental groups who tell it,” Middleton writes in the New York Times. “We need the confidence of the public if we are to provide trusted advice on policy issues. This is especially true in the rural West, where we have altered landscapes in ways we cannot expect large carnivores to fix, and where many people still resent the reintroduction of wolves near their ranchlands and communities.”

Hunters, Heffelfinger argues, also have a vested interest in telling the true story of the Yellowstone wolf. In order to secure the continued support of the non-hunting public, hunters should strive to be seen as responsible, truthful conservationists.

“Especially as hunters who talk about how we’ve recovered elk and pronghorn and geese and mule deer, we should also be bragging about how we’ve brought the native predators back,” he said. “It may cost us some elk. But we can’t expect the 95% of the public that doesn’t hunt to continue to support us if we say we don’t want wolves on the landscape. That’s not going to generate support from non-hunters.”

“The future of hunting is not in the hands of anti-hunters and their criticisms,” Heffelfinger concluded. “The future of hunting is in the hands of hunters who must continue to be seen as a positive force for overall conservation by the general public.”

To do that, Heffelfinger says, we shouldn’t oversimplify the role of wolves in Yellowstone even if that story might convince some people to support reintroducing the native species.

After all, as Middleton put it in a 2016 piece for National Geographic, “It’s an unproven theory that gets undue attention in the quest to have wolves shine rainbows out of their asses.”

Did Wolves Really Start a Trophic Cascade in Yellowstone?

You’ve seen the video. Narrated by British environmental activist George Monbiot, “How Wolves Change Rivers” tells the incredible story of how gray wolves sparked a cascading series of ecological benefits for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. “We

www.themeateater.com

자료 1. “How Wolves Change Rivers”

https://youtu.be/ysa5OBhXz-Q?si=nrQC8aTedH2_ZXqe

2015-sep4-Did wolves help restore trees to Yellowstone?

Science Sep 4, 2015 3:30 PM EST

Twenty years on from their reintroduction into Yellowstone National Park, wolves are still howling. But does their presence spell good or bad tidings for other wildlife?

“Since about 2008 our wolf numbers have been fairly flat,” said Doug Smith, who heads the National Park Service’s Wolf Project at Yellowstone. His group reintroduced 31 wolves into the park in 1995 and 1996, and he says there are now roughly 100 wolves – down from a peak of 174 in 2004.

Studies continue to reveal how the wolves are impacting the populations of large, high profile prey, such as elk and bison. Yet ecologists are taking a broader, more comprehensive view of the wolves’ impact on the larger ecosystem.

In the case of trees, that turns out to be a tall order. Park rangers monitor aspen stands throughout Yellowstone – including one in the Crystal Creek area of the park. Two decades ago, it was just a fraction of its current size.

Utah State University wildlife ecologist Dan MacNulty recently walked through the Crystal Creek aspens, on his way to inspect the carcass of an elk that had been just been killed by wolves on a ridge just above.

“When I started in the late ’90s, none of these aspen were here,” MacNulty said, who heads a long-term study to assess the impact of wolves on animal communities in the park. “If they were here, they were very, very small and since then, there’s been a lot of growth.”

The Gibbon wolf pack standing on snow. Photo by Doug Smith/Via National Park Service

When wolves were reintroduced in 1995, about 18,000 elk grazed Yellowstone’s northern range, and many aspen stands were struggling. Harsh winter conditions often drove elk to nibble on aspen branches – what ecologists call “browsing.”

“When you have a lot of snow on the ground, you don’t have access to the grass,” MacNulty said. “And so what those elk would do, they’ll come into here and because these aspen shoots are above the snowpack, they’ll browse on them, they’ll eat them.”

Aspen and other trees that grow near them – like willow – had traditionally served as nesting areas for birds and had provided wood for beaver dams. When the number of trees declined, bird and beaver populations did too.

Now, twenty years later, the Yellowstone elk herd population stands at about 4,500 animals – and the aspen trees at Crystal Creek have shot up in height.

National Science Foundation’s Science Nation on Yellowstone wolves feat. PBS NewsHour correspondent Miles O’ Brien

“The question is: Do these changes have anything to do with the wolf reintroduction?” MacNulty said. “Is it due to wolves scaring elk out of areas that are risky? Is it due to wolves driving elk numbers down, so there are few elk around to feed on these aspen trees?”

But that’s a tough link to prove, because there are so many environmental variables at play. Most significantly, a multi-year drought was in full swing right around the same time as the wolf reintroduction. Aspen and willow trees need a lot of moisture to grow. In fact, MacNulty says there has been a long-term drying trend in Yellowstone since records started to be kept in the late 1800’s.

It’s a source of active debate and there is no consensus on whether the aspen decline was caused by long-term drought, over-browsing by elk, or a combination of the two, MacNulty said.

Dan MacNulty and colleague tracking and observing elk just outside Yellowstone’s Roosevelt Arch, near Gardiner, Montana. Photo by National Science Foundation

Whatever the cause, the re-emergence of the tree stands has park officials closely monitoring the animals that depend on them – like the birds and especially beaver. Beaver dams on streams and creeks raise the water table in the vicinity, increasing moisture levels and fostering the growth of even more trees.

“What’s going to happen with the beaver?” said National Park Service biologist Dan Stahler. “Are they going to proliferate or are they going to maintain their low numbers? If they proliferate then you could expect to see some pretty major changes in Yellowstone.”

The return of the wolf has even helped other carnivores to thrive.

“Grizzly bears, black bears, coyotes, wolverines even, foxes, even birds will scavenge off carcasses…eagles, ravens all those meat eaters benefit by the protein that the wolves leave on the landscape that would otherwise be bound up into live animal,” MacNulty said.

There is general agreement that a wide diversity of species is a healthy thing for the larger community of animals. For now, the wolf population is holding its own.

“I think where we’re at now is pretty much what we expected 20 years ago,” Smith said. “Unless there’s some kind of a major change – of course, climate change is a huge wrench in everything – we think this could be some kind of long-term equilibrium.”

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/wolves-greenthumbs-yellowstone

Did wolves help restore trees to Yellowstone?

Wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park two decades ago, and scientists are still keeping a close eye on their ecological impact.

www.pbs.org

3.

Turns Out Wolves Really Do Change Rivers, After All-Posted by Richard Conniff on March 10, 2014

UPDATE FRIDAY MARCH 30: At the suggestion of a reader, I’m changing the title of this item–formerly “Maybe Wolves Don’t Change Rivers, After All” to reflect the consensus of scientific research noted in my updates before and after this article.

UPDATE MONDAY FEBRUARY 19 2018, new study supports the hypothesis that wolves have changed the character of stream-side vegetation at Yellowstone.

UPDATE SATURDAY MARCH 25 2016: PLEASE NOTE THAT ARTHUR MIDDLETON (below) and all other ecological researchers agree that reintroducing wolves to their former home range across the American West is a major benefit to wildlife and healthy habitats. It is also essential. All this article says is that the results are not as quick or simple as some environmentalists want to believe:

The story of how wolves transformed the Yellowstone National Park landscape, beginning in the 1990s, has become a favorite lesson about the natural world. A video recounting (above) has gone viral lately, with British writer George Monbiot re-telling the story in his best breathy David Attenborough.

The only problem, according to field biologist Arthur Middleton, writing in today’s New York Times, is that it isn’t true.

I don’t like the NYT headline “Is the Wolf A Real American Hero?” which seems to fault the wolf for our myth making. But otherwise, this op-ed is a good reminder that nature is almost always more complex than the stories we tell about it :

FOR a field biologist stuck in the city, the wildlife dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History are among New York’s best offerings. One recent Saturday, I paused by the display for elk, an animal I study. Like all the dioramas, this one is a great tribute. I have observed elk behavior until my face froze and stared at the data results until my eyes stung, but this scene brought back to me the graceful beauty of a tawny elk cow, grazing the autumn grasses.

As I lingered, I noticed a mother reading an interpretive panel to her daughter. It recounted how the reintroduction of wolves in the mid-1990s returned the Yellowstone ecosystem to health by limiting the grazing of elk, which are sometimes known as “wapiti” by Native Americans. “With wolves hunting and scaring wapiti from aspen groves, trees were able to grow tall enough to escape wapiti damage. And tree seedlings actually had a chance.” The songbirds came back, and so did the beavers. “Got it?” the mother asked. The enchanted little girl nodded, and they wandered on.

This story — that wolves fixed a broken Yellowstone by killing and frightening elk — is one of ecology’s most famous. It’s the classic example of what’s called a “trophic cascade,” and has appeared in textbooks, on National Geographic centerfolds and in this newspaper. Americans may know this story better than any other from ecology, and its grip on our imagination is one of the field’s proudest contributions to wildlife conservation. But there is a problem with the story: It’s not true.

We now know that elk are tougher, and Yellowstone more complex, than we gave them credit for. By retelling the same old story about Yellowstone wolves, we distract attention from bigger problems, mislead ourselves about the true challenges of managing ecosystems, and add to the mythology surrounding wolves at the expense of scientific understanding.

The idea that wolves were saving Yellowstone’s plants seemed, at first, to make good sense. Many small-scale studies in the 1990s had shown that predators (like spiders) could benefit grasses and other plants by killing and scaring their prey (like grasshoppers). When, soon after the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone, there were some hints of aspen and willow regrowth, ecologists were quick to see the developments through the lens of those earlier studies. Then the media caught on, and the story blew up.

However, like all big ideas in science, this one stimulated follow-up studies, and their results have been coming in. One study published in 2010 in the journal Ecology found that aspen trees hadn’t regrown despite a 60 percent decline in elk numbers. Even in areas where wolves killed the most elk, the elk weren’t scared enough to stop eating aspens. Other studies have agreed. In my own research at the University of Wyoming, my colleagues and I closely tracked wolves and elk east of Yellowstone from 2007 to 2010, and found that elk rarely changed their feeding behavior in response to wolves.

Why aren’t elk so afraid of the big, bad wolf? Compared with other well-studied prey animals — like those grasshoppers — adult elk can be hard for their predators to find and kill. This could be for a few reasons. On the immense Yellowstone landscape, wolf-elk encounters occur less frequently than we thought. Herd living helps elk detect and respond to incoming wolves. And elk are not only much bigger than wolves, but they also kick like hell.

The strongest explanation for why the wolves have made less of a difference than we expected comes from a long-term, experimental study by a research group at Colorado State University. This study, which focused on willows, showed that the decades without wolves changed Yellowstone too much to undo. After humans exterminated wolves nearly a century ago, elk grew so abundant that they all but eliminated willow shrubs. Without willows to eat, beavers declined. Without beaver dams, fast-flowing streams cut deeper into the terrain. The water table dropped below the reach of willow roots. Now it’s too late for even high levels of wolf predation to restore the willows.

A few small patches of Yellowstone’s trees do appear to have benefited from elk declines, but wolves are not the only cause of those declines. Human hunting, growing bear numbers and severe drought have also reduced elk populations. It even appears that the loss of cutthroat trout as a food source has driven grizzly bears to kill more elk calves. Amid this clutter of ecology, there is not a clear link from wolves to plants, songbirds and beavers.

Still, the story persists. Which brings up the question: Does it actually matter if it’s not true? After all, it has bolstered the case for conserving large carnivores in Yellowstone and elsewhere, which is important not just for ecological reasons, but for ethical ones, too. It has stimulated a flagging American interest in wildlife and ecosystem conservation. Next to these benefits, the story can seem only a fib. Besides, large carnivores clearly do cause trophic cascades in other places.

But by insisting that wolves fixed a broken Yellowstone, we distract attention from the area’s many other important conservation challenges. The warmest temperatures in 6,000 years are changing forests and grasslands. Fungus and beetle infestations are causing the decline of whitebark pine. Natural gas drilling is affecting the winter ranges of migratory wildlife. To protect cattle from disease, our government agencies still kill many bison that migrate out of the park in search of food. And invasive lake trout may be wreaking more havoc on the ecosystem than was ever caused by the loss of wolves.

When we tell the wolf story, we get the Yellowstone story wrong.

Perhaps the greatest risk of this story is a loss of credibility for the scientists and environmental groups who tell it. We need the confidence of the public if we are to provide trusted advice on policy issues. This is especially true in the rural West, where we have altered landscapes in ways we cannot expect large carnivores to fix, and where many people still resent the reintroduction of wolves near their ranchlands and communities.

This bitterness has led a vocal minority of Westerners to popularize their own myths about the reintroduced wolves: They are a voracious, nonnative strain. The government lies about their true numbers. They devastate elk herds, spread elk diseases, and harass elk relentlessly — often just for fun.

All this is, of course, nonsense. But the answer is not reciprocal myth making — what the biologist L. David Mech has likened to “sanctifying the wolf.” The energies of scientists and environmental groups would be better spent on pragmatic efforts that help people learn how to live with large carnivores. In the long run, we will conserve ecosystems not only with simple fixes, like reintroducing species, but by seeking ways to mitigate the conflicts that originally caused their loss.

I recognize that it is hard to see the wolf through clear eyes. For me, it has happened only once. It was a frigid, windless February morning, and I was tracking a big gray male wolf just east of Yellowstone. The snow was so soft and deep that it muffled my footsteps. I could hear only the occasional snap of a branch.

Then suddenly, a loud “yip!” I looked up to see five dark shapes in a clearing, less than a hundred feet ahead. Incredibly, the wolves hadn’t noticed me. Four of them milled about, wagging and playing. The big male stood watching, and snarled when they stumbled close. Soon, they wandered on, vanishing one by one into the falling snow.

That may have been the only time I truly saw the wolf, during three long winters of field work. Yet in that moment, it was clear that this animal doesn’t need our stories. It just needs us to see it, someday, for what it really is.

Richard Conniff is an award-winning science writer. His books include The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (W. W. Norton, 2011). He is now at work on a book about the fight against epidemic disease. Please consider becoming a supporter of this work. Click here to learn how.