스웨덴 청년 주거 상황 (20대)

논문 제목. 스웨덴에서 청년 주거와 배제

저자: 매츠 리벡

책 제목: young and housing (청년과 주택,주거)

YOUTH HOUSING AND EXCLUSION IN SWEDEN-Mats Lieberg

Introduction

Sweden as a welfare state has historically been considered strong, with an ambitious

housing policy. However, since the early 1990s there has been a decrease in

housing subsidies and a rolling back of the welfare state (Birgersson 2009). These

changes have been associated with rising house prices and costs, which have

worsened young adults’ chances on the housing market. This chapter examines the

effects of housing on the lives of young Swedish people, with the aim of providing

an overall picture of young people’s housing situation in Sweden. The current

housing situation and future housing expectations of young people 20–27 years

old living in Sweden are analysed and discussed. The diffi culties and obstacles

facing young people are described and the mechanisms leading to marginalization

and exclusion from the housing market are identifi ed. The topic of exclusion is

dealt with by studying a group of marginalized young people receiving social

welfare benefi ts. The chapter concludes with a discussion on various proposed

solutions which could help to improve the situation of young people in the

housing market.

The chapter is based on three kinds of scientifi c material: (1) a survey of literature

and secondary data sources available, including research reports, scientifi c articles,

statistical information, national and government reports, offi cial documents and

reports or practical examples; (2) a quantitative study from 1997, repeated in 2009,

based on a random sample of 2000 young people aged between 20 and 27, who

were interviewed about their present housing situation, their housing history and

their preferences for future housing; and (3) a qualitative study from 1997, based on

semi-structured in-depth interviews with 15 adolescents and ten social workers,

which examined the housing situation among a group of marginalized young

people.

108 Mats Lieberg

Sweden in an international perspective

From an international point of view, young people in Sweden have access to a high

standard of housing as regards quality and spaciousness (SOU 1996; SCB 2008a).

Young people in Sweden also tend to leave their parental home at an earlier age

compared to their peers in other parts of Europe, especially compared to those

living in the Southern and Eastern parts of Europe. Housing standards are similar

throughout Sweden, whether young people live with their parents or independently

(Lieberg 1997a). Homelessness and temporary accommodation, for example young

people’s hostels or institutions, are rare (Socialstyrelsen 2006). A long and stable

Swedish housing policy with high state subsidies has contributed towards this trend.

Sweden and other societies in EU-Europe can be characterized as ‘modernmodernizing’ societies (Bendit et al. 1999). They are mainly service economies in

which structural and technological changes give rise to social and cultural modernization processes. Most of these societies, including Sweden, can be characterized

by a growing complexity and diversity, resulting in diffi culties and insecurities for

different groups of the population, especially young people.

Contemporary developments in different life spheres and age levels within these

societies have been successfully interpreted within the wider theoretical context,

with the concepts of ‘individualization’ and ‘social differentiation’ (Beck 1992)

playing important roles as analytical descriptors. ‘Individualization’ refers to longterm processes of social change and describes the continuous decline in the normative power and resilience of social milieus and cultural traditions which accompanies

socio-economic and technological development (Bendit et al. 1999: 20). Young

people’s housing situation as well as the processes of ‘leaving home’ or ‘staying in the

parental home’, further discussed in this chapter, must be interpreted and understood

in this wider context.

Recent data collected from the Eurostat Labour Force Survey show that, in the

EU in 2008, 46 per cent of all young adults aged 18–34 still lived with at least one

of their parents (EU-Communities 2009). The proportion of young adults aged

18–34 living with their parent(s) varies from 20 per cent or less in Sweden, Denmark

and Finland, to 60 per cent or more in Bulgaria, Slovenia and Slovakia. It exceeds

50 per cent in 16 Member States. In France, 48 per cent of young people aged

18–30 live at home, in Spain 78 per cent. Unlike the Scandinavians and the British,

the Spanish do not consider this a major problem.

It is interesting to see that, while in the northern EU countries very small changes

are documented during the last twenty years, in the southern part of Europe a

signifi cant growth in the rate of those living in the parental home was recorded

(EU-Communities 1996, 2009). Different hypotheses have been put forward to

explain these changes: in Southern and Eastern Europe a general shortage of

affordable housing, combined with diffi culties in entering the labour market, as well

as important changes in values connected to family tradition and culture, are the

main explanations, while in Scandinavia and northern Europe the prolongation of

the youth phase is often mentioned as the main explanation for longer periods of

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 109

time remaining in the parental home. A Finnish study supports the assumption that

a sharp slowdown in growth, coupled with high unemployment rates, makes it

more diffi cult for young people to afford ‘independent’ living (Harala 1996). The

consequences of this may include effects on young people’s professional careers and

on establishing their own way of life, and delayed childbirth.

Housing conditions for young people in Sweden

Recent research indicates that the position of young people in the Swedish housing

market is becoming increasingly diffi cult (Bergenstråhle 2009; Enström 2009).

Many young people would like to have their own home, but a combination of the

situation in the housing market and the lack of a steady income has resulted in them

either being forced to remain in the parental home or having to fi nd a dwelling

with less secure tenure (Lindén 2007). The cost of living in Sweden has increased

substantially over the last ten years, mainly due to lower state subsidies and increased

construction costs (Turner 1997; Enström 2009).

The number of smaller, cheaper

fl ats has decreased drastically (SOU 1996). Many landlords are intensifying demands

on their tenants, even insisting on a steady income, a ‘healthy’ bank account, a clean

credit record, etc. In addition, the current level of youth unemployment in Sweden

is the highest since the depression in the 1930s. According to the Statistics Sweden

(SCB 2008a), the open rate of unemployment among young people aged 20–23

reached 20 per cent in November 2008. A further 5 per cent can be added for those

engaged in one or other of the labour market’s programmes for the unemployed.

Few people anticipate any radical changes within the next few years. Since 2002

there has been almost complete stagnation in the construction of new housing as a

consequence of unemployment and decreased state subsidies.

Housing and the Swedish welfare state

Housing has played an important role in Swedish welfare politics for a long time,

and has been closely associated with the Swedish welfare state. Housing has been

regarded as the right of the individual, based on his or her needs and preferences. In

many respects this ambitious housing policy has not been able to prevent increasing

segregation, and in some places extremely impoverished housing environments

(Nordin 2007).

Movement of people between different areas, migration from the countryside

to the city and increasing immigration created segregated residential areas during the 1970s and 1980s (Musterd and Andersson 2006). Wealthy households

gradually left these areas to move to better homes in other areas. The Million

Program areas were drained of resource-rich groups, which found new abodes in

1980s detached and semi-detached housing areas. Poor families and immigrants

were left behind in the suburbs. Many of these also moved within and between

suburbs in an endeavour to fi nd the right place in the ‘new’ community. There

developed an ethnic and social/economic segregation as a result of which children

110 Mats Lieberg

and young people grew up in widely different situations, some in secure and stable

conditions, others in a fractured and uncertain social environments (Wirtén 1998).

This social uncertainty became a greater burden for economically and socially

deprived groups than for others.

A combination of a new tax and funding system for housing and substantially

reduced state subsidies has contributed to increased housing costs, especially as

regards construction of new housing (Birgersson 2009).

This situation has

undoubtedly had an effect on young people trying to enter the housing market.

This re-structuring of society meant changes in relations not only between

private households and the local community, but also within families. Many

marriages and civil partnerships broke down and new family constellations

were formed. Many of the young people interviewed had experiences of

family break-up and its consequences, in the form of a constant struggle to be

accepted by or to accept new family members – stepfathers and stepmothers, new

siblings, etc.

Data from a recent study suggest that family background has now become an

important factor in determining young adults’ housing situation (Enström 2009).

Young adults with parents who are owner-occupiers and whose fathers have a

university degree seem to have become more likely to buy their housing. The results

also indicate that growing up with a single parent – a factor that has been shown to

put children at risk – now also seems to have become a constraint on choice in the

housing market. The results of this study indicate that the housing opportunities of

young adults may have become a matter of class affi liation (Enström 2009: 2).

The 1990s in Sweden have been described as a period of fundamental change.

Sweden’s entry into the international community and the integration of the

Swedish economy and politics with the European market prepared the ground for

a new situation in the housing sector. Simultaneously, one of the pillars of the

‘Swedish model’, i.e. full employment, collapsed, and Sweden has now joined the

ranks of other European countries with high unemployment fi gures. There is every

reason to believe that this will seriously affect the distribution of income, increase

poverty and create an increasing tendency towards social marginalization.

The structure of the housing stock

Of the almost 4,000,000 homes in Sweden, about 75 per cent have been built since

World War II. The joint housing stock has seen a substantial decrease in the number

of small fl ats (SCB 2008a). Demolition and renovation have resulted in a diminishing

number of single-room fl ats and other small fl ats lacking kitchen facilities since

1960. The number of two-room fl ats with a kitchen and bathroom decreased from

59 per cent to 34 per cent during the period 1960–1990. In addition, structural

changes in households and family building have resulted in the number of singleperson or two-person households increasing from just over 47 per cent to 71 per

cent during the same period. As a result, competition for fl ats is very high (Boverket

2007; Birgersson 2009).

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 111

Flexibility in the housing market is currently relatively low. This especially affects

young people, in particular those under 25 years of age who are not seeking newly

built fl ats. These young people depend on established households moving on up the

‘housing ladder’, thereby releasing cheaper fl ats onto the housing market.

About half (54 per cent) of Sweden’s households live in blocks of fl ats. The

remainder live in small or single-family houses. When it comes to forms of tenure,

41 per cent of Swedish households own their own homes, 40 per cent rent and 16

per cent live in owner-occupied properties (SCB 2008a).

The typical Swedish

pattern is for small or single-family houses to be owned by individuals, while blocks

of fl ats are owned by public associations or housing co-operatives. Large fl ats are

found in small housing developments and small fl ats are found in blocks of fl ats.

There are obvious regional differences in the housing stock. In sparsely populated

areas, 95 per cent of the housing stock consists of small houses, whereas in

metropolitan areas this fi gure is 30 per cent and in other urban areas it is 45 per cent

(SCB 2008a).

Actors in the housing market

In recent years, there have been a number of changes in the Swedish housing

market and its actors (Boverket 2007). The aim has been to deregulate the market

and to gradually transfer the responsibility for building and housing to landlords

and households (Birgersson 2009). The consequence of this is that government and

municipal responsi bility for housing has changed and diminished.

The earlier role of the state as regards norms, standards and levels of ambition has

disappeared, or rather moved on into the hands of other actors in the fi eld. Building

legislation has been rewritten. The rules and regulations that previously applied to

state grants have become more general in character. This has opened the door to

new possibilities for building houses with different forms, standards and quality. This

can allow young people to gain access to cheaper and somewhat less traditional

housing.

Housing benefi ts have been the responsibility of the state since 1994. The state

has also decided to cut interest allowances. This has led to an increase in the cost of

new-builds and house renovation over the last few years.

The municipalities have also experienced changes in housing policy. Since 1993,

they no longer have to provide a housing programme and there are no longer any

housing departments. The individual landlord now has to advertise vacancies. In

principle, this means that housing goes to the household which best suits the owner

of the property. The municipalities are only responsible for the weakest groups in

society – those on social benefi ts or in need of special support or care as regards

housing.

The landlords have been given a freer hand in fi nding their tenants. By shifting

the security of tenure, landlords can more easily give notice to troublesome tenants.

On the other hand, tenants have been given a longer time to pay rent arrears before

being evicted.

112 Mats Lieberg

How do young people in Sweden live today?

The results of the 2009 national study showed that 21 per cent of young people in

the age group 20–27 still live in the parental home (Table 6.1). This is compared to

15 per cent in the 1997 study. However, there are certain differences between age

groups. The majority of young people in the age group 18–19 (86 per cent) still live

with their parents. Only a few (8 per cent) have gone as far as fi nding their own

dwelling. Of those aged 20–23, 33 per cent live with their parents. Of the 24–27

age group, 85 per cent have their own home and 8 per cent live with their parents.

The majority appear to leave home when they are about 21.

If we look more closely at how young people actually live and compare this with

the preference profi le, we fi nd that the majority have had a fairly good start in life.

As a rule, young people live in small, modern homes. Of all the young people aged

between 18 and 27 who have left home and are neither married nor cohabiting, just

over half (57 per cent) have their own home, comprising one room, kitchen and

bathroom or less. A further 33 per cent live in a fl at with two rooms, bathroom and

kitchen and 16 per cent have a larger home. There are also differences between the

individual age groups. Of the few 18–19 year olds who have left home and not yet

started to build a family, 63 per cent have their own home with one room, bathroom

and kitchen or less. Fifty-fi ve per cent in the age group 22–23 and 45 per cent in

the age group 24–27 live in a fl at of one room, bathroom and kitchen or less. It is

primarily university or college students who live in one room, with or without

a kitchen (41 per cent). Many young people in this group have one room and a

kitchenette. Those who are married or cohabiting with no children always live in a

larger dwelling than those who are living on their own. However, it should be

noted that 7 per cent of young people live in a fl at with one room, bathroom and

kitchen or less.

Nearly all young people live in well-equipped accommodation with toilet and

bathroom (98 per cent), kitchen or kitchenette (97 per cent) and deep freeze (94

TABLE 6.1 Percentage of young people in different types of housing according to age, 2009.

Accommodation type Age group (%)

20–23 years 24–27 years 20–27 years

Living with parents 33 8 21

Independent home 42 73 57

Student accommodation 9 4 7

Sublet 8 9 9

Living with friends 4 2 3

Other 4 4 3

Total 100 100 100

Source: SKOP, national survey, 2009

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 113

per cent). The majority of homes also have a TV (96 per cent) and a stereo (96 per

cent). Many have computers (64 per cent), primarily the homes of young people

attending university or college, or secondary school. More men than women have

computers and more young people in the lower age groups than in the higher age

groups. More young people living at home have computers than those who have

left home.

The process of leaving the parental home

The results from the 1997 Swedish national study show that, when young

people leave the parental home for an independent home, this is a step in their

effort to gain independence and enter adulthood (Lieberg 1997b). The act of

leaving home is determined by several factors: the young person’s own economic

resources (income, capital) are crucial. Extending education means that it takes

longer before a young person can earn an income. This, in turn, delays a young

person’s ability to leave the parental home. This applies in particular to teenagers

(at secondary school) and, to a certain extent, young people in their early 20s.

Longer periods of study after secondary school have resulted in young people

having to move abroad or to other parts of Sweden and therefore leaving home at

an earlier age.

Viewed over a longer period of time, living in the parental home in Sweden

has gradually declined. Up to the end of the 1960s, the severe housing shortage

presented an obstacle for young people wanting to leave home (Boverket 2007).

One million new homes were built during the ten-year period between 1965 and

1975 in the so-called Million Programme. During this time, the number of young

people living in the parental home decreased considerably (Ungdomsstyrelsen

1996). The reason was the availability of an additional number of large fl ats, which

presumably led to a lengthy chain of people moving home that resulted in smaller

fl ats becoming available for young people.

Viewed over a shorter period of time, there has been an increase in the number

of the youngest young people (teenagers) living in the parental home, but a decrease

among the older group of young people (Table 6.2). In 2010, 89 per cent of

teenagers were still living in the parental home, compared with 76 per cent in 1975.

Even among 20–24-year-olds, it appears that living at home has increased during

this period, whereas it has decreased or been more stable among those aged 25–29.

Young women in Sweden generally leave their parental home at a lower age than

their male peers. Up to age 25 differences span a range of 10 to 15 percentage

points, but after 25 they inevitably become smaller. The 1997 study showed that at

an age of 28 or more, 12.1 per cent of young men and 7.3 of young women still

lived in the parental home. These gender differences represent a general pattern

found in Swedish (Lindén 2007; Bergenstråhle 1997, 2009) as well as international

studies (Jones 1995; Bendit et al. 1999).

On the other hand, what was not so familiar in the past is a signifi cant number

(20 per cent) of those who have left home for some reason returning to the parental

114 Mats Lieberg

home (Lieberg 1997b). This new phenomenon, sometimes referred to as ‘boomerang

kids’, has started to become quite common in Sweden. A ‘boomerang kid’ is a term

used to describe an adult child that has left home at some point in the past to live

on their own and has returned to live in the parental home. This return can be due

to completed studies, divorce or unemployment – or lack of affordable housing. In

2001, almost 25 per cent of all adult children living with their parent(s) in Sweden

were boomerang kids. And a majority of them were boys. So, leaving home today is

no longer a fi nal process. Many young people, and especially young boys, return to

their parental home not only once but many times during the ‘extended period of

youth’. It is therefore more relevant to talk about being ‘on probation from home’,

than ‘leaving home’ (Jones 1995; Lieberg 1997b).

Leaving home for good possibly does not happen until the young person is

much older. In addition, various contributing factors relating to changes in the

structure of the modern family must be considered, for example many young

people share their housing between their mother and father, who may live in

different places and who may have entered a new relationship and started to build

a new family (SCB 2008b). These factors show that leaving home is indeed a much

more complex and lengthy process than before.

A considerable number of these young people have economic reasons for

returning home, for example they have lost their job, or could not afford their

independent home. Today a large number of young people living at home are

waiting to enter the housing market as soon as it is fi nancially possible. Research in

Sweden and abroad has shown that the transition to adulthood and leaving home is

complicated, largely infl uenced by the changing family structure and by issues

concerning employment, study and independent living (Löfgren 1991; Lindén

2007; Enström 2009). Increased knowledge of the long-term effects of remaining at

home is therefore an important issue for research.

It is unusual in Sweden for young people to remain living in the parental home

once they have started to build a family. Further, young people do not normally

leave home to live with a partner, but usually begin by fi rst living independently

TABLE 6.2 Percentage of young people in Sweden still living in the parental home,

1975–2010.

Age group Percentage living in the parental home

1975 1980 1985 1990 1997 2000 2005 2010

16–17 95 97 98 97 98 98 99 98

18–19 76 77 80 79 88 87 88 89

20–24 37 34 35 30 37 38 39 43

25–29 10 8 8 6 9 10 11 12

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, Population and Housing Register 1997 and Total Population

Register 2010

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 115

for a short period of time. Remaining in the parental home is strongly related to

the young person’s position on the labour market. Figures from 1991 show that

only 20 per cent of those gainfully employed still lived in the parental home, while

72 per cent of young people who were studying lived in the parental home (Löfgren

1991).

Mobility aspirations

A number of studies show that young people are a mobile group within the housing

market. Like a pendulum, they swing between different, sometimes temporary,

housing solutions – from living in the parental home to student accommodation,

from staying with friends to sublets, etc. In 1996 the number of young people in the

age group 20–29 registering a change of address was three times greater than the

national average (Bergenstråhle 1997). It is extremely diffi cult to obtain data about

the period between leaving home and fi nding an independent dwelling, usually at

about 20–21 years old. According to the Population and Housing Register for

1990, about 66,000 young people out of a total of just over 1,000,000 (6.7 per cent)

did not belong to a so-called household in that year. These young people were

registered as living in a parish or property but did not actually live there, or they

were young people with no permanent home or who did not want to divulge

where and with whom they were living (Ungdomsstyrelsen 1996).

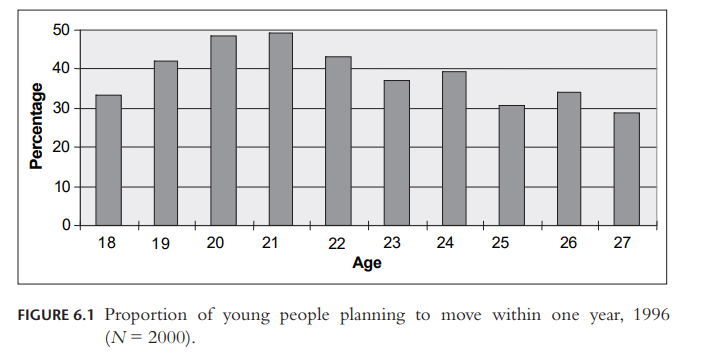

In response to the question ‘Do you plan to leave home within the coming year?’

a total of 38 per cent of young people aged 18–27 replied that they did. The

majority (44 per cent) of these were in the 22–23 age group. When individual

groups were studied, it was found that almost half the 20–21 year olds said they

planned to leave home within the next year (Figure 6.1). In order to fi nd out the

exact frequency of leaving home, the young people were also asked how many

times they had moved within the last two years. Naturally this varied according to

age. In all, 66 per cent had left home at least once during the past ten years. Of this

FIGURE 6.1 Proportion of young people planning to move within one year, 1996

(N = 2000).

Percentage

Age

50

40

30

20

10

0

18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

116 Mats Lieberg

66 per cent, more than a quarter had moved back home again three or more times.

It would appear that young people are an extremely mobile group in the housing

market.

Role of unemployment and other economic factors

A combination of developments in the labour market and access to smaller and

cheaper dwellings is clearly controlling the possibilities for young people to leave

home. In a situation of high unemployment and a housing market in recession, as

has been the case in Sweden since the 1990s, the chances of young people fi nding

an independent dwelling decrease. This in turn results in more and more of them

being forced to remain in the parental home. Some have to return to the parental

home for fi nancial reasons, after having lived independently for some time.

The national surveys show a strong link between a young person’s position on the

labour market and living at home. The number of young people living at home

increases among the unemployed and decreases among the securely employed.

Compared with those that have left home, to a great extent those young people

still living at home are either in temporary employment or unemployed, or are

engaged in a labour market youth training scheme. In all, 13 per cent of the young

people in the 2009 survey regularly received fi nancial support from their parents.

This was especially common in the youngest age group, where 29 per cent received

support. A large number of those young people receiving regular fi nancial support from their parents were secondary school pupils (38 per cent), those living

with their parents (24 per cent), those doing their national service (23 per cent) or

those enrolled in some kind of government training scheme for the unemployed

(22 per cent).

This indicates that many young people receive fi nancial support and allowances

to cover their living costs from different sources. Apart from housing benefi ts and

rental support from their parents, young people can receive help to cover living

costs from unemployment benefi t or from regular fi nancial support from their

parents. A total of 36 per cent received some kind of fi nancial assistance to cover

housing costs. Very few received support from more than one of the fi ve different

sources of fi nancial assistance mentioned in our questionnaire (Bergenstråhle 2009).

Youth homelessness and the housing situation

among marginalized young people

According to a study by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare in

2010, there are about 30,000 homeless people in Sweden. This is approximately

double the number found in a similar study in 2005 (Socialstyrelsen 2006). In

addition, there is probably a large number of unknown cases, especially among

young people who turn to various temporary and often non-contract housing

arrangements. The homeless make up around 0.3 per cent of the Swedish population.

Three quarters of the homeless are male and one quarter female, and there is an

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 117

over-representation of people born outside Sweden. Very few have any work or

salaried income, so many are dependent on benefi ts. Substance abuse and mental

health problems are common among the homeless, but there are also homeless

people without such problems.

A large proportion of the homeless (38 per cent) are in the age range 30–45

years and approximately 25 per cent are in the range 18–29 years. It is in these

younger age groups and among women that the increase in numbers is greatest. In

addition, there are unknown numbers of children who were not actually recorded

in the investigation. Statistical data for Malmö, Sweden’s third largest city, confi rm

that the increase in the number of homeless, with the exception of a few years in

the beginning of the 2000s, has been constant in the past ten years.

During the 2000s, long-term dependency on benefi ts in Sweden has developed

into something that does not affect only homeless people, substance abusers and

dysfunctional families. Increasing unemployment and uncertainty in the labour

market have resulted in more groups becoming dependent on the support of society

(Salonen 1993, 2007). Despite this, those receiving benefi ts are still regarded as

people who are unwilling or unable to support themselves, which in turn often

contributes to feelings of consistently low self-esteem and a generally pessimistic

self-perception.

The young people interviewed in 1997 as part of the qualitative study left the

parental home earlier than others. Many of them had left home as 16- or 17-yearolds and lived in their own fl at, often together with a boyfriend or girlfriend

(Lieberg 1998). Leaving home so early is otherwise uncommon in Sweden. Only

around 2 per cent of all young people of this age have left home. While their fi rst

home of their own was important for them, it was not always easy fi nancially or

socially. Many have had diffi culties supporting themselves after leaving school

which led to them losing their home. Girls often had diffi culties in their relationships

with older boyfriends. For many girls, having a boyfriend and moving in with him

presented an immediate opportunity to move away from the family home. In

particular, for girls without close female friends and without a job, a boyfriend

represented an opening to a more adult and independent life. The boyfriend became

their rescuer from childhood dependency on the family. It emerged in the interviews

with these girls that the boyfriend was not always the man they had wanted, but

their dependence on him made it diffi cult for them to end the relationship. The

boyfriend was also not always the one they wanted to be the father of their future

children. Despite this, some of them had babies at an early age, perhaps because

their identity as a mother was important to them. Having a baby gave them the

opportunity to alter the picture of themselves and their life, as they took on the new

identity of mother and parent.

A new culture of unemployment is developing

Mass unemployment at the beginning of the 1990s and during the economic

crisis in 2008–2009 has left its mark, although in recent years unemployment in

118 Mats Lieberg

Sweden has been slowly decreasing. Between the lines there are glimpses of another

truth – for the young, the group which experiences the greatest diffi culty in fi nding

work, the situation is still serious.

An investigation by Linköping University found that a new culture of unemployment is developing, especially among those young people who fi nd it most diffi cult

to enter the labour market (Hallström 1998). This culture is characterized by young

people simply contenting themselves with state-run youth employment measures.

They are unwilling to embark on long-term education and demand that society

organize work and occupation for them. The decrease in youth unemployment in

the past year has naturally altered the picture, but tragically there is always one

group left out. The young people in the 1990s were the fi rst in over 60 years to

experience such a constrained labour market.

In our own data, there was a distinct contrast between the views of young people

and offi cials interviewed as regards society’s responsibility to organize work. This

confl ict probably also partly refl ects the generation gap that exists in attitudes to

work, with young people in Sweden appearing to resemble those in other European

countries with high and permanent unemployment (Gabriel and Radig 1999). In

such countries there is no parallel drawn between livelihood and work.

Future housing

As regards young people’s housing demands in Sweden, it appears that traditional

values steer demands for future housing. Today, young people’s ideas about their

future housing are not especially daring. A clear majority could certainly consider

making a personal contribution to reducing housing costs. Specialist youth housing

and ‘eco housing’ also appear to attract young people’s interest. Otherwise, as regards

maintaining a high standard of housing, it appears that the young people of today

share the same values as past generations. This was indeed noticeable in the 1997

survey when it came to attitudes on future housing. A clear majority expressed a

preference for having their own house with a garden, near the countryside. The

question is whether Sweden is ever going to be able to afford such a high standard

of housing again. Young people are not particularly interested in specifi c housing

solutions. The majority said that the best way for young people to enter the housing

market would be to reduce youth unemployment and thereby enable young people

to pay their housing costs.

Final discussion

This chapter has shown that young people in Sweden tend to leave the parental

home somewhat later in life than previously. The reasons for this are prolonged

studies combined with increased housing costs and changes in the housing market.

There is no evidence to indicate that this increase in young people remaining at

home is the result of a change in attitudes among young people. Rather, it is the

result of structural and economic factors. When there is high unemployment and an

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 119

uncertain economy, many young people, and especially boys, choose to remain

living at home, and an increasing number return home to live with their parents.

‘On probation from home’ or ‘boomerang kids’ is therefore a more appropriate

expression than ‘leaving home’. This is a new and important phenomenon that has

not previously been included in Swedish research, since earlier studies concentrated

on the fi nal move from home and not the fi rst move. The process of returning

home appears to have been neglected because of diffi culties of gaining access to the

data and because leaving home has been assumed to be a one-off phenomenon.

However, as returning home has become more common in recent years, in Sweden

and in other countries, the process of leaving home may be considerably more

complicated and lengthier than previously thought. It is also important to consider

the differences between marginalized youth and the mainstream. Young people

with social problems tend to leave the parental home much earlier than others.

These changes can be important in other ways, too. The national housing policy

appears to be built on a model of economic rationality, which presupposes that

young people will only leave home when they can afford to do so. Measures aimed

at reducing the reasons for leaving home therefore automatically prolong the period

in which young people live in the parental home. The effects of this are not especially

apparent in Sweden as yet, but international research shows that many young people

who leave home while quite young do so because of domestic confl icts, lack of

space and diffi culties in getting employment or studying in their home town (Coles

1995; Gabriel and Radig 1999; Enström 2009). Thus they often have no choice in

the timing of leaving home. They are almost certainly not prepared to live in an

independent home and they do not have the economic means for this. Although the

situation in Sweden cannot be compared with the international situation, any

developments that lead to youth exclusion in the housing market should be

monitored. According to Jones (1995), the ‘normative’ pattern for moving home is

largely built on economic rationality, while moving home because of marriage,

work or studies is largely based on individual choice. The latter is therefore more

sensitive to manipulation by different forms of state regulation and contributions.

This chapter shows that young people remaining at home and leaving home is a

special area for research, and illustrates some of the related problems. It also shows

the importance of continued research, not least as regards young people returning

to live in the parental home and the increased economic responsibility on the

family for young people who have reached the age of majority. Research should

focus on ethnicity, gender, class and regional differences and on access to subsidies

for different groups. Much research to date has focused on what the process means,

mainly for marginalized and socially burdened households, so studies are needed on

‘whole’ families, without economic and social problems. Such studies should also

examine the parents’ viewpoint as well as young people’s and view the young

person’s situation from both a family perspective and from a broader perspective

within society.

When carrying out future studies about young people moving home, it must be

made clear whether it is the fi rst time of leaving home, the last time or a mixture of

120 Mats Lieberg

both. It is critical for young people seeking to free themselves from their parental

home to set up home for themselves that good quality data are available to politicians

and decision-makers. Cross-sectional studies that build on temporary households

are therefore greatly limited, and comparisons with other studies should be avoided

if the same defi nitions and methods of measurement are not used. The best results

can be obtained from longitudinal studies, in which the same defi nitions and

methods are used on many occasions to fi nd trends and important changes in

development, followed by deeper qualitative studies on a more individual level.

References

Beck, U. (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Bendit, R., Gaiser, W., and Marbach, J.H. (eds) (1999) Youth and Housing in Germany and the

European Union. Hemsbach, Germany: Leske + Budrich.

Bergenstråhle, S. (1997) Ungas boende. En studie av boendeförhållandena för ungdomar i åldern

20–27 år. (Young people and housing. A study of young people’s housing in the age groups 20–27.)

Stockholm: Boinstitutet.

Bergenstråhle, S. (2009) Unga vuxnas boende – förändringar i riket 1997–2009 (Young people’s

housing situation – national developments 1997–2009), Rapport 1: 2009. Stockholm:

Hyresgästföreningen.

Birgersson, B.-O. (2009) Bostaden en grundbult i välfärden. En förstudie om levnadsvillkor och

boende – del ett. (Housing as a fundamental of welfare. A pilot study on living conditions and

housing – part 1.) Stockholm: Hyresgästföreningen.

Boverket (2007) Bostadspolitiken – Svensk politik för boende, planering och byggande under 130 år.

(Housing Policy. Swedish politics for housing, planning and building over 130 years.) Karlskrona:

National Board of Housing, Building and Planning.

Coles, B. (1995) Youth and Social Policy. London: UCL Press.

Enström, C. (2009) The Effect of Parental Wealth on Tenure Choice – A Study of Family Background

and Young Adults’ Housing Situation, Arbetsrapport 2009: 1. Stockholm: Institutet för

framtidsstudier.

EU-Communities (ed.) (1996) Labour Force Survey. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

EU-Communities (ed.) (2009) Youth in Europe 2009. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Gabriel, G. and Radig, S. (1999) ‘Housing support for young people at risk: a qualitative

study’, in R. Bendit, W. Gaiser and J. H. Marbach (eds) Youth and Housing in Germany and

the European Union. Hemsbach, Germany: Leske + Budrich.

Hallström, B. (1998) Arbete eller bidrag. En attitydundersökning bland arbetslösa ungdomar och

ledande kommunalpolitiker. (Work or allowance. A study of attitudes among unemployed youth and

local politicians.) Rapport 1998: 2. Linköping: Linköpings universitet.

Harala, R. (1996) Monitoring Youth Exclusion in Finland. Helsinki: Statistics Finland.

Jones, G. (1995) Leaving Home. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lieberg, M. (1997a) Youth Housing in Sweden: A Descriptive Overview Based on a Literature

Review. Mälardalen University: Welfare Reseach Centre.

Lieberg, M. (1997b) On Probation from Home: Young People’s Housing and Housing Preferences in

Sweden. Mälardalen University: Welfare Research Centre.

Lieberg, M. (1998) Bostäder och boende bland unga socialbidragstagare – en kvalitativ studie.

(Dwellings and housing among young people with social allowances – a qualitative study.)

Mälardalen University: Welfare Research Centre.

Lindén, A.-L. (2007) Hushåll och bostäder. En passformsanalys. (Household and housing. A

correlation analysis.) Lund: Sociologiska institutionen, Lunds universitet.

Youth housing and exclusion in Sweden 121

Löfgren, A. (1991) Att fl ytta hemifrån. Boendets roll i ungdomars vuxenblivande ur ett

siuationsanalytiskt perspektiv. (Leaving home. The role of housing in young people’s transition to

adulthood from a situation analytical perspective.) Diss. Lund: Lund University Press.

Musterd, S. and Andersson, R. (2006) ‘Employment, social mobility and neighbourhood

effects: the case of Sweden’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(1):

120–140.

Nordin, M. (2007) ‘Ethnic segregation and educational attainment in Sweden’, in

M. Nordin, (ed.) Studies in Human Capital, Ability and Migration. Lund: Nationalekonomiska

institutionen, Lunds universitet, 107–132.

Salonen, T. (1993) Margins of Welfare: A Study of Modern Functions of Social Assistance. Lund:

Hällestad Press.

Salonen, T. (2007) Barnfattigdomen i Sverige. (Poverty among Swedish Children.) årsrapport.

Stockholm: Rädda Barnen.

Socialstyrelsen (2006) Hemlöshet i Sverige 2005. (Homelessness in Sweden 2005.) Stockholm:

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

SOU (1996) Bostadspolitik 2000 – från produktions – till boendepolitik. Slutbetänkande av

bostadspolitiska utredningen. (Housing policy 2000 – from production to housing policy.) Final

committee report from The Housing Policy Report. Swedish Government Offi cial

Reports 1996: 156. Stockholm: Fritzes.

SCB, Statistiska Centralbyrån (2008a) Boende och boendeutgifter 2006. (Housing and housing

costs 2006.) Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

SCB, Statistiska Centralbyrån (2008b) Ungdomars fl ytt hemifrån. (Leaving home.) Stockholm:

Statistics Sweden.

Turner, B. (1997) Vad hände med den sociala bostadspolitiken? (What happened to the social housing

policy?) Stockholm: Boinstitutet.

Ungdomsstyrelsen (1996): Krokig väg till vuxen. En kartläggning av ungdomars livsvillkor. (The

winding road to adulthood. Mapping young people’s living conditions.) Youth Report 1996

part 1. Stockholm: Ungdomsstyrelsen (National Board for Youth Affairs).

Wirtén, P (1998) Etnisk boendesegregering. (Ethnic housing segregation.) Stockholm: The Institute

of Housing Studies.

출처 책

'도시계획' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 도심 변화. 1913년 ~ 2024년. Christie and Davenport in 1913,Toronto, Canada (0) | 2024.02.18 |

|---|---|

| 조세희 , ‘난장이가 쏘아올린 작은 공' 150만부. 300쇄. 사람들이 난쏘공을 읽는 이유. “당분간 우리는 모든 싸움에서 지기만 할지 모른다. 그러나 우리는 최선을 다하지 않으면 안 된다.” - .. (0) | 2024.02.16 |

| 토론토 도심 변화. Trinity-St. Paul's United Church, 1890, 1977, 2023 (0) | 2024.01.22 |

| 도시 공간. 길거리 공연과 광장 문화, 지하철 내부, 큰 상가 (0) | 2024.01.02 |

| The University Theatre on Bloor in Toronto in 1949 (0) | 2023.12.16 |

| 1915년 하수도. 토론토. 게리슨 크릭 쑤어. 1915, the Garrison Creek sewer (0) | 2023.12.05 |

| 건축. 지붕 모양 roof type (1) | 2023.11.27 |