아이란 쿠르디, 3세 아가의 죽음을 보면서, 드는 생각은 본질적으로 이 난민 문제와 '입양' 문제는 유사하다는 것이다. 그리고 두번째로는 꼬마의 가련한 슬픈 죽음이 있기 전에도 이미 수천명이 지중해 바다에 빠져 죽었다는 사실이다. 늑장 대응을 하거나 오히려 아프리카, 시리아, 아프가니스탄 전쟁 난민들을 돕지 않은 유럽 정치권들의 무능과 무책임은 이번 기회에 비판받아야 한다.

입양 이야기와 '난민' 문제가 서로 별개 것으로 보이지만, 부모님과 같이 다른 나라로 떠났느냐, 아니면 홀로 다른 나라로 갔느냐의 차이가 있을 뿐, 본질적으로는 같은 문제이다. 그래서 한국인들은 난민, 이주자들에 대해서 보다 더 많은 관심을 가져야 한다.

- 2015년 1월 영국 bbc 뉴스에 실린 한국입양 문화 역사와 해법에 대해서 알아보자.

한국은 수출국가이다. 그런데 또 하나의 수출 1위가 있다. 그것은 바로 한국 어린이와 아가들의 해외 (미국) 수출이었다. 그런데 경제성장과 번영의 상징이 된 한국은 이제 입양수출을 자제하고 있고, 그 조건도 까다롭게 고쳤다. 2005년, 1200명이었던 해외 입양은 이제 10분의 1로 줄어들었다. 그 대신 한국내 입양이 늘어나고 있다. '수출'이라는 용어는 분명히 오해가 있고, 잘못되었다. 하지만 역사적 현실이었다.

기사에 따르면 미국 입양이 많았던 이유, 그리고 아직 한국 내 입양에 대해서도 '쉬쉬'하는 이유는, '피 순혈주의'와 '가족중심주의' 문화 때문이라고 평가하고 있다. 그리고 채용, 고용시에도, 아버지가 누구냐 어머니는 뭐하시냐를 묻는 '한국특유의 가족주의' 문제점도 지적하고 있다. 채용하는데 아버지 어머니 이름과 그들의 직업이 무엇인가를 따져 묻는 것은 또 다른 '차별주의'이다.

한국내 입양이 활성화되기 위해서는 '입양' 자체가 인생 '오점, 결함'이 되어서는 안된다고 영국 뉴스는 강조하고 있다.

언제까지 세계 최고 수준의 학력과 배움의 전당, 한국이, 이러한 영국 bbc 뉴스의 '계몽' 대상이 되어야 하는가?

. 아이의 명복을 빕니다. 우리 모두의 책임임을 알리는 꼬마의 죽음.

Taking on South Korea's adoption taboo

- 6 January 2015

- Asia

It used to be said that South Korea's biggest export was babies - Korean children, unwanted in their own land, were adopted by loving new parents outside the country, particularly in the United States.

And then the law was changed. The shame of an increasingly affluent and confident country sending its children abroad to find the love denied at home played on the national conscience so foreign adoption was made much harder.

On top of that, rules were tightened so the unwanted children of unwed Korean mothers had to be registered before adoption.

'Didn't dare tell'

The changes were made with good intentions. Adopted children might want to trace their birth parents so registering full details seemed like a helpful measure.

And why should Korea depend on American parenting, particularly as South Korea became prosperous? Didn't it smack of colonialism?

But the good intentions have led to unintended results: South Korean orphanages are now brimming with children who might previously have found a new life in a foreign family.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTen years ago, 1,200 Koreans were adopted abroad. Today, it's a tenth of that figure.

The problem is that adoption in Korea is taboo, so the gap left by the fall in foreign adoptions has not been filled by adoptive Korean parents.

Those who do adopt sometimes do it in secret.

When Choi Hyunjin was adopted, her new, adoptive parents kept it secret even from their own close relatives.

The couple sit on their sofa in a high-rise apartment near Seoul and say with one voice: "We didn't even dare tell our own parents because we knew they would disapprove. They would only say 'Why are you bringing up other people's children'?"

But Mr and Mrs Choi persevered and now they are among a band of adoptive parents who testify in meetings and go to schools to preach the worth of the love which adoption brings to estranged and abandoned children.

Familial past

The taboo arises because the importance of blood-lines in Korea is ancient and deep-rooted. Korean Confucianism places great emphasis on ancestors.

Hollee McGinnis, a Korean-American who was herself adopted and who now researches how adoption affects personality in later life, told the BBC: "Family is everything in Korea. Who you are and your character is based on your family so if you do not have information about your family, you might find yourself having barriers in life."

She said these barriers can even extend to a block on employment.

AFP

AFP"In Korea, your potential employer can ask for your family registry. Your family registry has all the information about your relatives. If you cannot produce a family registry that might be a reason for them not to hire you.

"When you write a letter applying for a job, in your cover letter in the West we talk about education, our skills, our experiences. In Korea, they talk about your family - what your dad did; what your mum did - so your character is based on your family."

This means that orphans - who cannot explain their familial past - have a hard time of it.

Those involved in adoption over many years are in some despair.

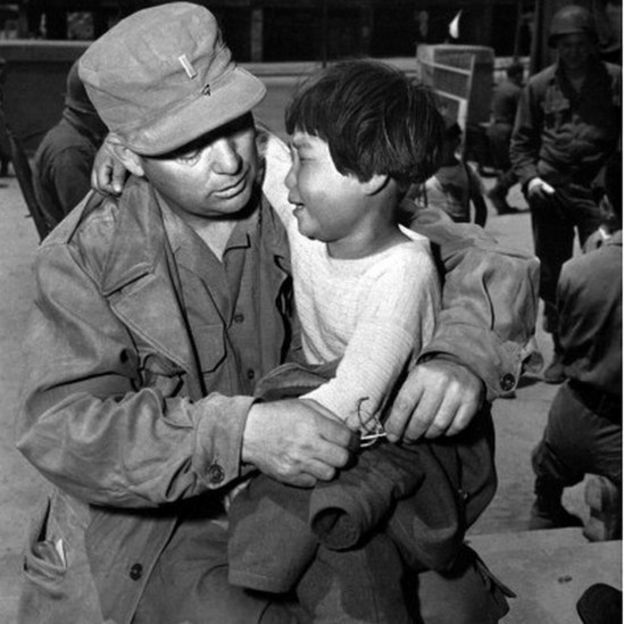

In 1955, an American couple Harry and Bertha Holt moved from Eugene, Oregon and set up an orphanage in South Korea, moved by the plight of orphans after the Korean war, particularly those with black American fathers and Korean mothers who found it particularly hard to be accepted in Korean society.

Six decades on, their daughter, Molly, continues their work. She deplores the effect of the compulsion on women to register their children: "If they do, they can't ever marry because no husband wants to marry a woman who has had a baby. So now, so many babies are being abandoned.

"They used to have two babies abandoned a month before the law came into existence and now they have 25 a month. And those babies can't be adopted overseas. They can only be adopted by Koreans, and Koreans don't like to adopt."

'Blessed with adoption'

One answer would be to persuade more Koreans to adopt. The taboo would go if the stigma on adoption was eased.

Attempts are made to do this. The Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea was founded by a Korean who was adopted as a teenage and brought up in the United States.

Stephen Morrison spent eight years in an orphanage before his new parents transported him across the Pacific and transformed his life. He now thrives in Los Angeles as an engineer but returns to his old orphanage near Seoul.

"I came into this orphanage when I was six years old and I left when I was fourteen years old, and during that time I experienced a lot of hunger to be loved," he says.

"I was not a really good student but as soon as I was adopted into a family, I felt that immediate sense of care and love. All of a sudden, it was just magical: I started to excel in school and I want to pass on the blessings I got from adoption to other children that need homes."

When he returns to Korea, he meets his old street pals who were not adopted.

They have not thrived: "I grew up with my friends, my buddies and I'm still in contact with them. I feel I was so blessed with adoption. And yet my friends were not given that opportunity."

'정책비교 > 국제정치' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 시리아 내전 위기 원인, 피해 현황과 평화 안착 시도들 (0) | 2015.09.17 |

|---|---|

| 시리아 내전 난민 실제 상황 5가지 , PBS (0) | 2015.09.12 |

| 난민꼬마 쿠르디와 비슷한 처지, 한국내 미등록 외국인 노동자 자녀 학교 보내야 (0) | 2015.09.10 |

| 9월 1일, 세계 평화의 날, 무기 수출을 금지하자. (0) | 2015.09.01 |

| 전 세계가 주목하는 한반도 진보정치 ! ‘평화 기치’의 중요성 (3) | 2015.08.24 |

| [시리자 정부] 그리스 국민투표, 긴축정책 '반대' 61%로 압승 (0) | 2015.08.15 |

| 그리스 시리자, 3차 구제금융 협상, 트로이카에 굴복인가, 일보 전진을 위한 이보 후퇴인가 (1) | 2015.07.27 |