오늘 우연히 이코노미스트 '부고' 란에서 알게 되다.

1차 세계대전 이후 태어나 20세기를 중국 격변기와 함께 보내다.

청나라 마지막 황태자, 국민당 장개석, 중국 공산당 모택동 (마오쩌둥), 주은래(주은라이), 등샤오핑, 시진핑까지 동시대인으로 살았다.

1915-2023. 이사벨 크룩 2023년 8월 20일 별세.

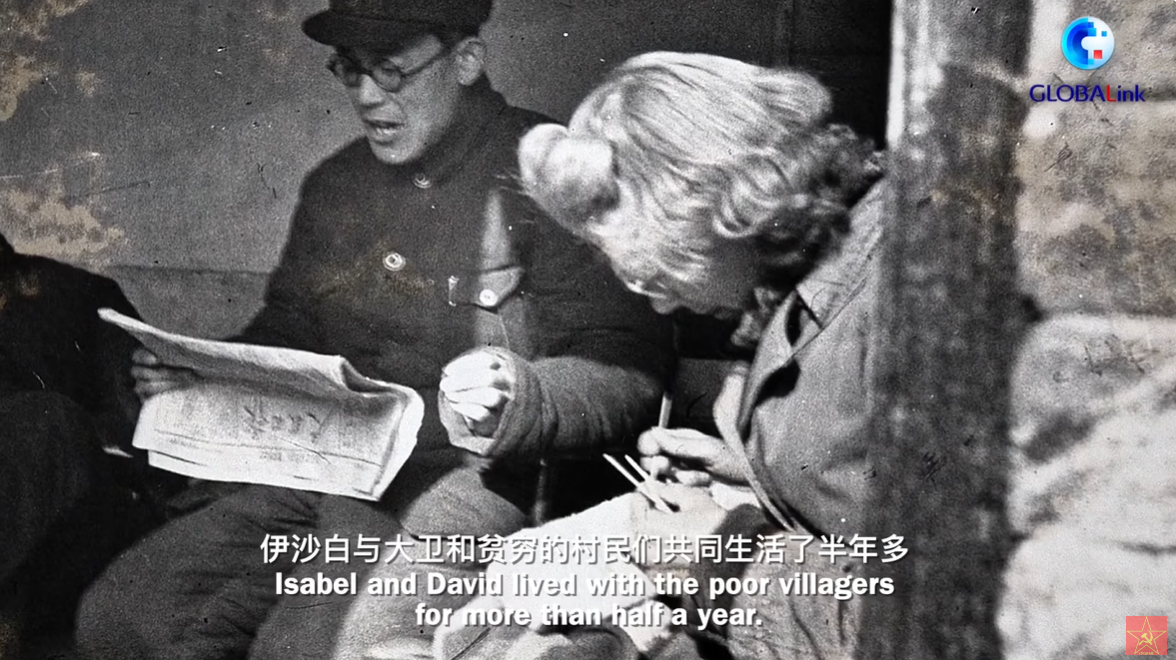

이사벨은 107년 생애 중, 90년간 중국에 거주하며 남편 데이비드와 함께 마오쩌둥 중국 혁명을 도우며 그 일생을 보냈다. 기사에 따르면, 이사벨과 데이비드는 베이징 외국어 대학에 거주하며 영어를 가르쳤고, 데이비드는 영-중 사전을 발간했다. 한영 사전이나 영한 사전도 그렇지만, 20세기 초반에 누군가 이렇게 번역을 했던 것이다.

이사벨과 남편 데이비드는 중국 공산당의 동지였지만, 문화혁명 시기에 데이비드는 스파이 혐의로 5년간 투옥되었고, 이사벨은 3년간 가택연금당했다.

이러한 부정적인 경험에도 불구하고, 그들은 중국을 떠나지 않았다. 그들의 아들 폴 (Paul)은 2011년 이사벨과 데이비드가 중국 문화혁명 시기에 벌어졌던 일들을 BBC뉴스에 기고했다.

중국 당국은 이사벨과 데이비드의 무죄를 선언했고, 공식적인 사과를 했다고 한다.

두 사람의 월급 역시 감금과 투옥 기간에도 지급되어, 세 아들들은 부모 월급으로 생활했다고 함.

중국과의 인연.

이사벨의 부모님은 캐나다 출신으로 감리교 신자들이었는데, 캐나다에서는 모르는 사이였다가, 1915년 중국 서부 쳉두에서 만나 결혼했다. 어머니 뮤리엘은 청각장애 어린이 학교를 운영. 아버지 호머 브라운은 중국어를 배워, 쳉두에 웨스트 차이나 유니언 대학을 개설했다. 이사벨과 줄리아는 캐나다 학교를 다녔다고 함.

토론토 대학 (빅토리아 칼리지)를 졸업하고 1939년 이사벨은 쳉두 서부에 있는 ‘이 Yi’ 소수 민족 (당시 이름. 롤로스 Lolos 족, 샤먼을 믿고, 노예제가 남아있음)을 조사하러 갔다.

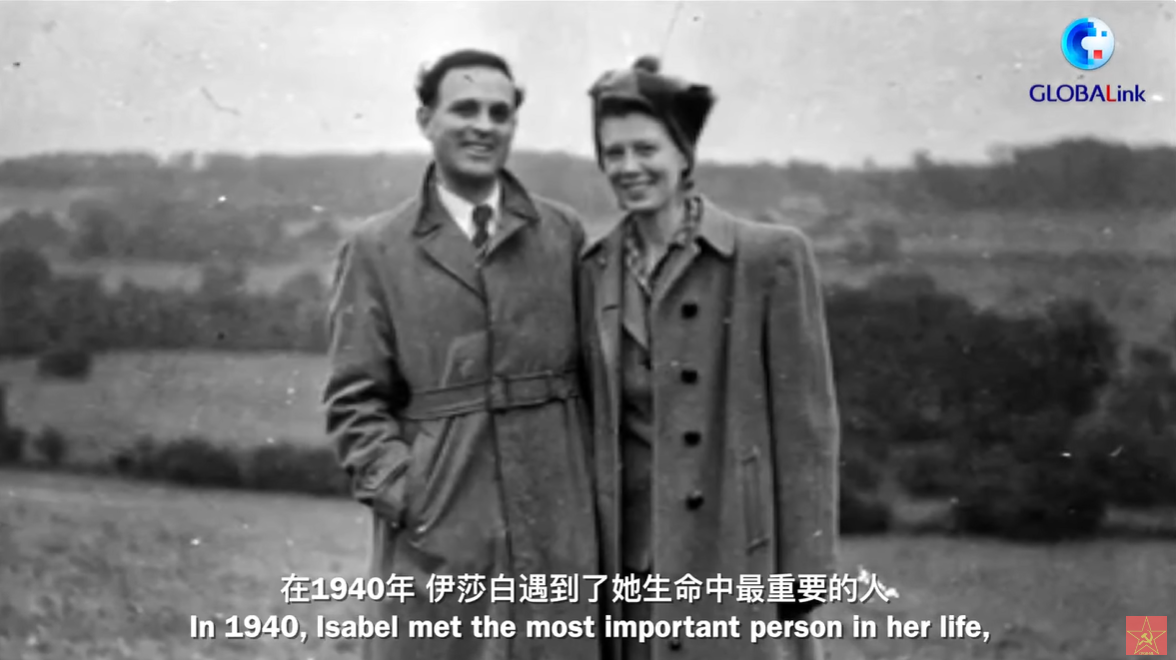

영국 공산당원 데이비드와 만남.

이사벨이 26세 (1941년) 되던 해, 영국 공산당 당원이었고, 스페인 시민내전에 자원병으로 참전했던 데이비드를 만나 결혼했다. 이후 이사벨은 중국 공산당에 가입했고, LSE(런던 경제학)에 박사과정에 입학했다. 그녀의 박사논문 주제는 중국 마을 Prosperity 에 관한 것임.

데이비드 크룩은 에드가 스노의 "중국의 붉은 별 Red Star over China"를 읽고 감명받았다고 함.

2차 세계대전 이후, 두 사람은 중국으로 돌아왔고 1년 반 정도 머무를 계획이었음.

2차 세계대전 당시 이사벨 크룩, 캐나다 군대 간호사 부대에 근무.

베이징 외국어 대학에서 중국 외교관들에게 영어를 가르치며 40년간 중국에 거주하게 됨.

이사벨과 남편 데이비드는 중국 공산당의 동지였지만, 문화혁명 시기에 데이비드는 스파이 혐의로 5년간 투옥되었고, 이사벨은 3년간 가택연금당했다.

2019년 시진핑은 이사벨 크룩에게 “외국인 최고 명예”를 뜻하는 ‘중국인의 우정 메달’를 수여했다.

이사벨은 중국에서 90년을 살았다.

데이비드는 2000년 중국에서 사망했다.

이사벨의 유족은 3명 아들, 칼, 마이클, 폴, 6명의 손자 손녀, 9명의 증손자, 그리고 여동생 줄리아.

---

이코노미스트에 실린 부고. 2023년 9월 9일자.

이사벨 크룩이 중국에서 한 일을 소개함.

Prosperity 마을, 1940년 중국 민족주의자 농업 개혁의 진보에 대한 기록.

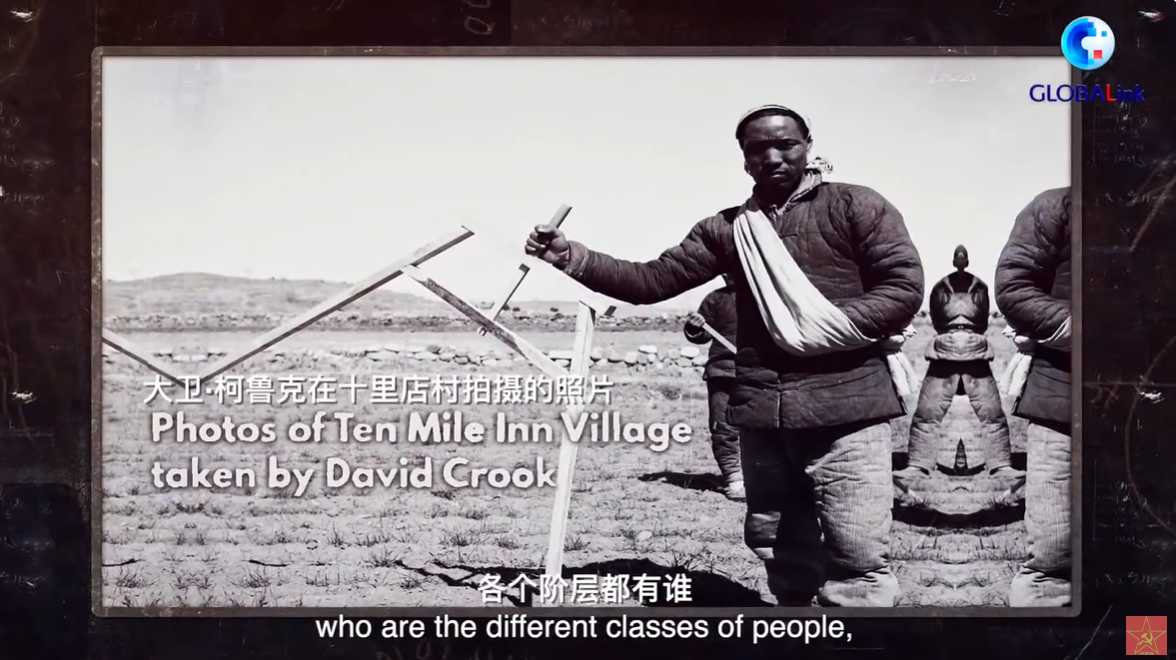

7년 후, 두번째 '10 마일 인' Ten Mile Inn, 1947년 공산주의자 통치 하에서 농업 경영 조사.

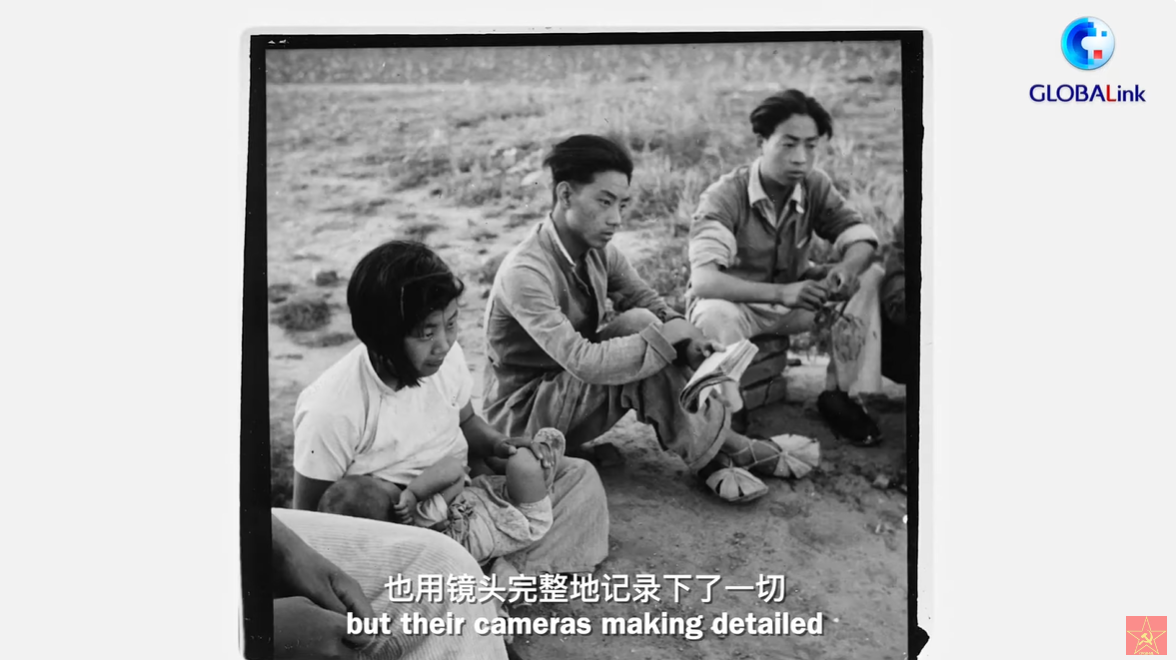

Prosperity 동네 중국인들의 삶.

1940년 산촌에서 곡선으로 된 계단식 논 (Prosperity 지역)

조사 팀, 인구 55%는 찢어지게 가난하고,

35% 중간층 농부들은 겨우 풀칠하고 살고 (get by)

나머지 10%는 부자층, 토지 소유층, 소작농에게 수확량의 60-70%를 받음. 아편 (opium) 무역

봄철이 되면 (춘궁기), 식량 부족으로, 동네 도적떼가 발생함.

장개석 중국 국민당 정부는 일본군과 싸우는 '강제 징모대'(Press Gang)였고, 엄청난 양의 세금을 거뒀고, 주민들에게 알려지지 않은 외부인들을 관리로 임명했다. 상황이 이렇다보니, 되는 게 아무것도 없었다.

Ten Mile Inn 위치.

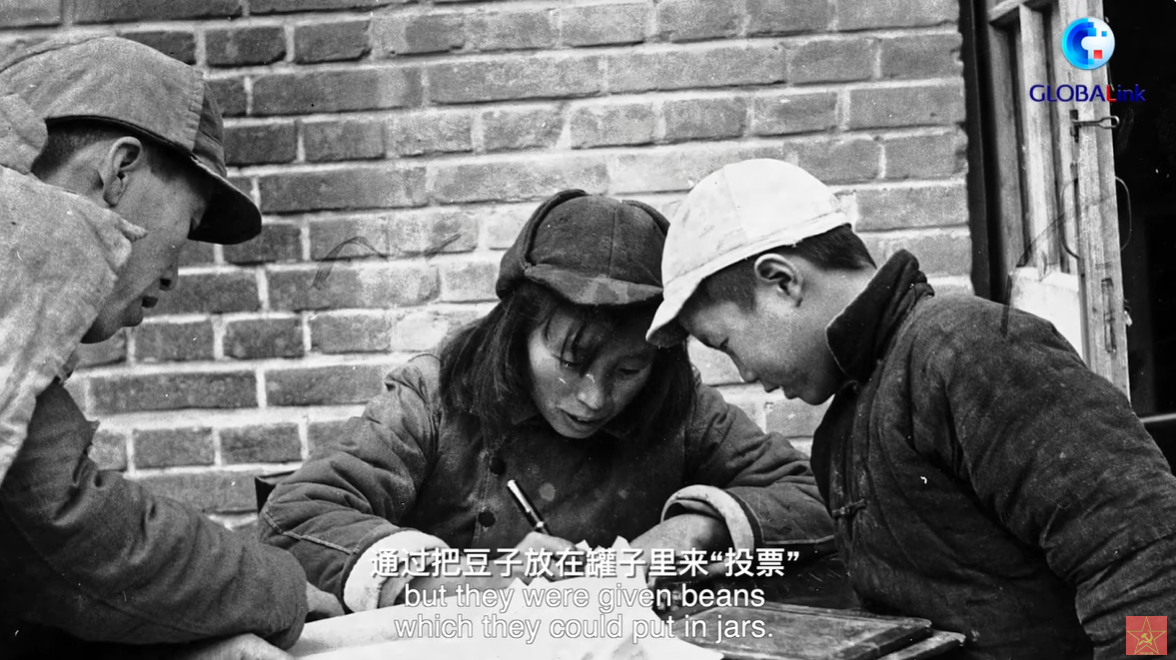

1947년 Ten Mile Inn 동네에서 보고서 - 어떻게 토지 분배를 했는가?

여기 역시 Prosperity 와 마찬가지로 가난한 동네지만, Prosperity 동네와는 다른 분위기.

국민당으로부터 최초로 해방된 동네. 마오쩌둥을 인민의 구세주로 부름. '인민해방군 PLA' 입대 지원서를 받음.

마을 주민의 70%는 세금 면제, 부자들만 세금을 납부하게 함.

토지와 재산을 다시 분배했다. 과거 봉건질서를 깨뜨리고 부를 다시 사람들에게 나눠줬다.

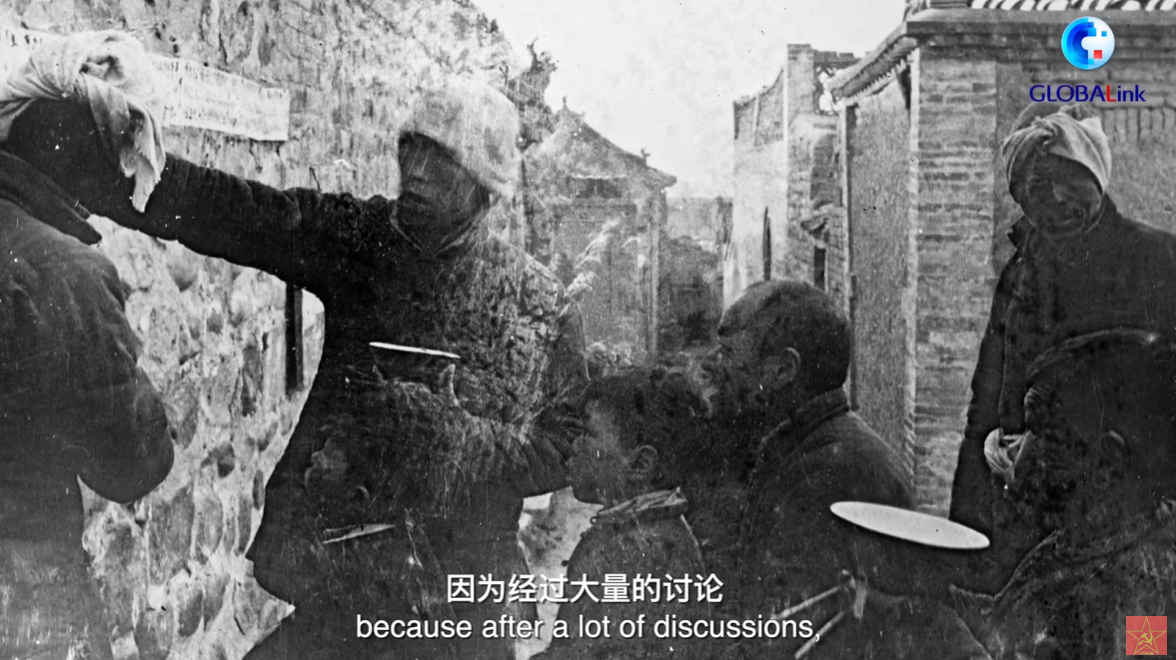

마을 사람들 대다수가 문맹이었으나, 중국 공산당은 이들과 대화를 통해서, 마을 일들에 참여하고,투표도 하게 했다.

이사벨은 이 토지와 재산 분배 과정을 기록했고, 데이비드는 사진도 남겼다.

'인민해방군'은 사람들 앞에서 '챙피를 주는 방식'으로 '공산당 정화운동'을 지원했다.

이사벨 크룩은 중국공산당의 몇가지 실수들도 기록했다.

국민당과 마찬가지로 중국공산당 (새 핵심 간부)도 특권을 행사하길 좋아했다. 아내가 될 여자들을 자기들이 먼저 선택한다거나 고기 만두를 실컷 더 먹는다거나.

선량한 동네 주민들이 고발당하거나 굴욕을 당하기도 했다. 마을 사람들은 서로 분열되어 서로 싸우기도 했다.

그럼에도 Ten Mile Inn 은 "혁명의 요새 (방어거점)"이 되었고, 마오쩌둥이 모든 동네가 이렇게 되길 바라던 바였다.

중국 인민들의 삶은 마오쩌둥 공산주의 하에서 이전보다 더 나아졌다. 어떻게 이사벨 크룩의 기록이 객관적이라고 할 수 있겠는가? 이런 질문을 던지는 이유는 이사벨 크룩이 공산당의 한 편이 되어서 중국 농부들과 함께 동고동락하며 밭일도 하고 수확도 도왔기 때문에, 이사벨 크룩의 보고서는 파당적이지 않냐는 질문도 있음.

이사벨은 감리교 집안에서 태어나, 기독교 전파를 위해 중국으로 간 부모님 영향으로 기독교 신자였으나, 이후 공산주의 혁명에 동조하고, 사회 변혁의 방법으로 채택했다고 함.

1958-1960년 대약진운동 (The Great Leap Forward) 기간에 1500만명이 죽었다. 이에 대해 이사벨 크룩은 의구심을 표출했지만, 이사벨의 남편 데이비드는 이 운동은 외과 수술처럼 급성 질병을 치료하는 것이라고 설명했다.

1967년~1973년 문화혁명 시기에, 데이비드 크룩은 체포되어 감옥에 투옥되었다.

이사벨은 가택 연금되었다. 그 기간 이사벨은 마오의 유머 감각을 즐기면서 그 책을 공부했다.

이사벨과 데이비드에게 가장 어려운 시기는 1989년 천안문 광장 시위였다. 그 둘은 시위 학생들에게 물과 플라스틱 판을 가져다 주었고, '중국인민일보 People's Daily'의 기고문에서, 중국 정부가 시위대에 무력을 사용하지 말라고 요청했다. 중국 정부는 무자비하게 시위대를 진압했지만, 그들은 여전히 중국에 남았다.

1970년대 후반 이후 등샤오핑이 추진한 개혁 정책으로, 현재 중국은 자본주의 시장 주도적이고, 소비주의적이고, 경제적으로 번영하게 되었다. 이사벨은 자본주의를 좋아하지 않았지만, 등샤오핑의 선택은 효과적이었다고 판단했다.

데이비드 크룩 흉상.

아들 마이클 크룩과 함께, 이사벨 크룩.

지도 출처. Ten Mile Inn : mass movement in a Chinese village

Crook, Isabel.2003

부고. Obituary

Isabel Crook obituary

Canadian anthropologist who joined Mao Zedong’s rural revolution and stayed on to build a ‘new China’

John Gittings

Mon 21 Aug 2023 17.42 BST

10

The pioneering anthropologist Isabel Crook, who has died aged 107, was the last survivor of that generation of sympathetic westerners who joined Mao Zedong’s rural revolution and stayed on after 1949 to build a “new China” – with mixed fortunes.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) her husband David Crook was accused of spying and imprisoned for five years, while Isabel was locked up for three years on their college campus. The couple retained their belief in the post-Mao leadership of the Communist party until, horrified by the Beijing massacre in Tiananmen square (1989), they spoke out against it.

Yet the buffeting of Chinese politics under Mao and after that dominated their lives and those of many others who “stayed” should not obscure Isabel’s remarkable career from an early age pursuing anthropological fieldwork in remote and difficult areas of China.

Isabel’s parents, Muriel (nee Hockey) and Homer Brown, were Methodist missionaries who left Canada separately and met at the West China Mission in Chengdu, marrying in 1915. Both were active in promoting public education, and Muriel opened schools for deaf Chinese children. Homer learned Chinese quickly and in time became dean of education at the West China Union University in Chengdu, where Isabel, and her sisters Muriel and Julia, were born and went to the Canadian School.

Isabel and David Crook. He was accused of spying and jailed for five years; she was confined to their college campus for three years.

Isabel and David Crook. He was accused of spying and jailed for five years; she was confined to their college campus for three years. Photograph: Crook family

In 1939, after graduating from Victoria College, University of Toronto, Isabel set off with a Chinese colleague to study the villages of the Yi minority people (known as Lolos then), a slave-based society who believed in shamans, in West Sichuan. They crossed a river “on rafts that sank ankle-deep beneath the surface … the current was so strong that we were carried miles downstream.”

It was opium country and, as in other areas where she would work, there were “bandits”. But, Isabel would observe, they were really robbers, not bandits: “They were poor farmers in the off-season … they had to go up in the hills and come down and do their banditry.”

The following year, Isabel was recruited to join a rural reconstruction project sponsored by the Chinese National Christian Council in a desperately poor rural area not far from the wartime capital of Chongqing.

Her assignment was to conduct a major survey of the communities’ 1,500 families. “We set out on our household visits with stout sticks to beat off the ubiquitous dogs,” she would recall, but when the villagers saw they were unthreatening young women and not oppressive government agents, the dogs were called off.

Isabel intended to publish her work as Prosperity Village – it was even listed for a while by Routledge and Kegan Paul – but marriage, the revolution, and Mao intervened. The thousands of pages of field data remained in the desk until the 1990s when she returned to the area for more research which finally led to the publication of Prosperity’s Predicament: Identity, Reform and Resistance in Wartime China, with Christina K Gilmartin and Xiji Yu, in 2013.

When Isabel met David in 1941, he had been a committed member of the British Communist party for several years and a volunteer in Spain. Much later he would regret his role as a Soviet agent there spying on anti-Stalinists in Barcelona. He had been transferred by his handlers to Shanghai, but was obscurely dropped by them and made for Chongqing.

The couple agreed to get married in Britain and returned separately by dangerous routes. Isabel swiftly joined the Communist party and found herself standing outside Euston station and selling the Daily Worker. She soon enrolled for a PhD at the London School of Economics: her thesis was based on the Prosperity material. After the second world war, they returned to China, planning to stay for a year and a half. Instead they would remain in China till the end of their lives.

They headed for the communist “liberated areas” as the civil war with Chiang Kai-shek began to turn in Mao’s favour. David planned to write for British newspapers, hoping to emulate the US journalist Edgar Snow (who had interviewed Mao before the war). Isabel proposed to strengthen her thesis by studying another rural township with a different economic base.

It would be an exercise in applied anthropology, with research that could contribute to new development policy. Arriving in the chosen village by mule cart, they slept in peasant homes, lived on millet and sweet potatoes, and listened to “the musical chant of the doughnut pedlars”, while they got to grips with communist policy that would transform rural society.

This time it was Isabel’s plan that prevailed: David never became a journalist while her research, with which he helped, led to their classic account of one of the first land reforms in China (Revolution in a Chinese Village: Ten Mile Inn, 1959).

When the People’s Liberation Army entered Beijing in 1949, the Crooks watched the genuine enthusiasm, after years of Nationalist party misrule, with which it was greeted. “It is the most joyful [moment]”, Isabel recalled, “I think I’ve ever watched.”

Still planning to return to Britain, they were invited to stay and set up a foreign languages school to train new diplomats. In time this would become the Beijing Foreign Studies University, where they lived and worked over some four decades.

In 1959-60 Isabel and David returned to Ten Mile Village, now part of one of the new communes set up in the Great Leap Forward. They had no visible qualms about Mao’s attempt to speed up socialism by relying on mass enthusiasm, and they rejected “the doubts of some friends and the fears and obstructions of enemies”.

Yet, perhaps aware that there were serious problems elsewhere if not in this commune, they said that their study would be “strictly limited as to time and place”. The resulting book (The First Years of Yangyi Commune) was published in 1966 as Mao’s next wilful experiment began with the Cultural Revolution: it is a less satisfying account of rural reform and political struggle than was its predecessor Ten Mile Inn.

After release in 1973 from prison and confinement, the Crooks were vindicated, along with other foreign residents who had suffered, at a reception by then Premier Zhou Enlai, who sought to moderate the extremes of the Cultural Revolution. When Zhou died in January 1976, Isabel cycled through the snow to wait in the dark for his funeral cortege to pass – in vain because the ultra-left leadership (the Gang of Four led by Madame Mao) prevented any display of mourning.

The political climate improved after Mao’s death and the downfall of the Gang, but in 1989 the death of another popular leader, the former party secretary Hu Yaobang, would spark a new mass movement to challenge the authorities.

In May Isabel and David visited the student hunger-strikers in Tiananmen Square with bottled water and plastic sheets, and wrote to the official People’s Daily saying they “fervently hope[d] that no attempt will be made by China’s leaders to settle the present crisis by force”. Instead the Square became, as David would describe it, the Place of Massacre.

Appalled by the slaughter and by the official lies, the couple might have left China for ever – but they remained. They had stayed first in 1949, Isabel said, because they were participants “in a revolutionary movement embracing a whole people”, and their lives were inseparable from China whatever happened. Now, in retirement, they were given the status of advisers.

In 2019 Isabel was presented in person by President Xi Jinping with the Chinese Friendship medal, described as “the top honour for foreigners”. “I’m glad I did what I did”, Isabel told her son Michael in a film for Chinese television. She had spent 90 years of her life in China. “We belonged, and this is why we stayed.”

David died in 2000; Isabel is survived by their three sons, Carl, Michael and Paul, six grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren, and her sister, Julia.

Isabel Crook, anthropologist, born 15 December 1915; died 20 August 2023

(문화혁명 기간에, 남편 데이비드는 스파이 혐의로 5년간 감옥에 투옥되었고, 이사벨 크룩은 베이징 외국어 대학 자택에 3년간 연금되었다)

(1940년 25세. 이사벨 크룩)

출처. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/aug/21/isabel-crook-obituary

Isabel Crook obituary

Canadian anthropologist who joined Mao Zedong’s rural revolution and stayed on to build a ‘new China’

www.theguardian.com

books.

Book

Prosperity's predicament : identity, reform, and resistance in rural wartime China

Crook, Isabel.c2013

https://china.usc.edu/crook-et-al-prosperity%E2%80%99s-predicament-identity-reform-and-resistance-rural-wartime-china-2013

Crook et al, Prosperity’s Predicament: Identity, Reform, and Resistance in Rural Wartime China, 2013 | US-China Institute

Crook et al, Prosperity’s Predicament: Identity, Reform, and Resistance in Rural Wartime China, 2013

china.usc.edu

남편 데이비드와 문화혁명에 대한 언론보도. 데이비드, 이사벨의 아들 폴 (Paul Crook)

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-15063195

Growing up a foreigner during Mao's Cultural Revolution

The child of committed Communists, Paul Crook grew up in China under Mao Zedong. During the Cultural Revolution, both of his parents were imprisoned, leaving he and his brothers to fend for themselves.

www.bbc.com

Growing up a foreigner during Mao's Cultural Revolution

Published

27 September 2011

Paul Crook with his former friends

Paul Crook - back - was in school when the revolution began

(문화혁명이 시작되던 당시, 폴 크룩)

Paul Crook's Communist parents met in China in 1940 and brought up their three sons in Beijing. In the 1960s, Paul was caught up in the Cultural Revolution, a chaotic attempt to root out elements seen as hostile to Communist rule.

"We were encouraged to write posters criticising our teachers and the school leaders for anything seen as being 'Revisionist'.

My classmates and I would get big sheets of paper, poster size, and write all sorts of things and put them up in the classrooms and hallways.

If sometimes the teachers were not very nice to you, then this would be a chance to get back at them.

At the beginning there wasn't really much violence in my school, on the whole it was civilised, supposedly fighting against wrong ideas, but no doubt very demeaning, even horrific for many teachers.

A 1960s photo released by the Chinese official news agency of high school students, reading Mao's Little Red Book

Image caption,

Red Guard high school students read from Mao's Little Red Book

I do remember one of the more unruly students picked on an art teacher who was said to come from quite a bourgeois background.

He was one of the best teachers, I really liked him.

We were in a room with him and one of the other students had a baseball bat and was about to hit him and one of my friends said, 'Hey you can't do this'.

On that particular occasion we avoided any violence.

But elsewhere, there was much violence, as the Cultural Revolution went on.

'Bourgeois authorities'

Mobilised by Chairman Mao, millions of young people became Red Guards.

홍위병 (Red Guards)

They hounded anyone who they thought was sabotaging the Communist Revolution, many of them highly placed members of the Communist Party.

If you were noticed, a celebrity of any sort, you were fair game.

Academics, Party officials and others who were seen as being 'bourgeois authorities' were dragged off to meetings to be 'struggled against' in front of large crowds.

Many people were locked up - sometimes even killed or driven to suicide.

There was huge upheaval at the university where my parents, David and Isabel, worked.

At that time school students from the cities were regularly sent to work in the countryside during harvest season, and upon graduation many were sent to settle in the country, to share the life of the farmers.

In those days everyone in the countryside was a member of a 'People's Commune', working together, and sharing the proceeds.

In the autumn of 1967, I joined a bunch of foreign kids and went to a commune just outside Beijing, where we harvested sweet potatoes and pears.

It was a very happy time, but then when I came home three weeks later my brothers said, 'You'll never guess what has happened, they've arrested a spy at the university among the foreigners, can you guess who it is?'

I thought of a few relatively dodgy characters. But it turned out to be my father.

'Spy'

It was a bit of a joke because we thought, he believes in all this, supports the revolution, how could he be a spy?

We thought my father would be released within a few days, in a few weeks.

We had all been educated to think that things were getting better all the time, but sometimes there would be mistakes.

대중을 믿어야 한다, 그리고 당을 신뢰해야 한다.

One of the slogans at that time was: 'You should trust the Masses, and trust the Party!'

As I recall, I don't think I seriously thought that my father would ever not be released and I did not think he would be abused physically, so we just went on living.

We were constantly going to different government departments to find out where he was locked up, so we could deliver reading material to him or food that he liked.

My mother was repeatedly summoned for questioning and eventually she too disappeared.

이사벨 아들, 폴, 중국 공장에서 일할 당시.

Paul Crook working in a Chinese factory

Image caption,

Paul Crook with fellow workers at farm implements factory

By then the university was run by a Revolutionary Committee supervised by the Workers' Propaganda Team, and by army representatives sent to take control of universities by Mao.

아버지, 데이비드의 구속 기간에도, 부모님들의 월급이 지급되었다.

But my brothers and I continued to receive our parents' wages, and we were getting older, and were pretty well able to look after ourselves.

After I left school, I worked in a farm implements factory, and later an automobile repair plant.

We were anxious about what had happened to our parents, but we weren't eaten up by anger or worry, as we were brought up to believe that if you were innocent then this would be proved in due course.

Meanwhile my parents' friends gave us care and encouragement, and the official position towards young people whose parents were in trouble was that they could still be educated 'to take the right path'.

'The right path'

For a long time we thought it would just be a few months and we kept hearing things, rumours about the latest political twists and turns, and we thought - hoped - our parents would be coming out quite soon.

In the end my mother was freed after just over three years of lock-up on the university campus.

My father was released from prison after five years, much of it spent in solitary confinement.

이후 데이비드와 이사벨은 무죄 판명, 중국정부의 공식적인 사과를 받음.

신체적 고문을 당한 적은 없고, 감금당함.

He and my mother were later exonerated of any wrongdoing, and received an official apology.

My parents were never physically abused in all the time they were locked up, but it was a trying time, to say the least.

They were sustained by their belief that all this upheaval was part of an attempt to create a better society.

Although the time of my parents' incarceration was a period of turmoil in China, and we were concerned for our parents, it also was a time of independence for me and my brothers.

We had opportunities to travel around the country, and there was plenty of time for teenage fun, going out hiking in the hills, and parties and dancing in the Friendship Hotel, where foreign residents in Beijing lived a somewhat sheltered life.

Inevitably, what happened then shaped the way I saw the world.

Like many of my friends I grew to be rather sceptical, to be critical of what people's stated intentions were, and what their grand visions entailed.

Chairman Mao