Inequality-redistribution in Canada update

Posted by Edgardo Sepulveda under Canada, capitalism, Europe, inequality, Nordics, OECD.

March 18th, 2018

Comments: 2

Two years ago I posted my first guest blog focused on income inequality, specifically how changes in Canada’s redistribution over the last three decades have increased after-tax income inequality, and how these changes compared to OECD trends. The figures and analysis in this post update the earlier blog, based on the most recent OECD data to 2015. I also look at the market inequality-redistribution relationship and find that Canada is the only country that combines low market inequality with low redistribution.

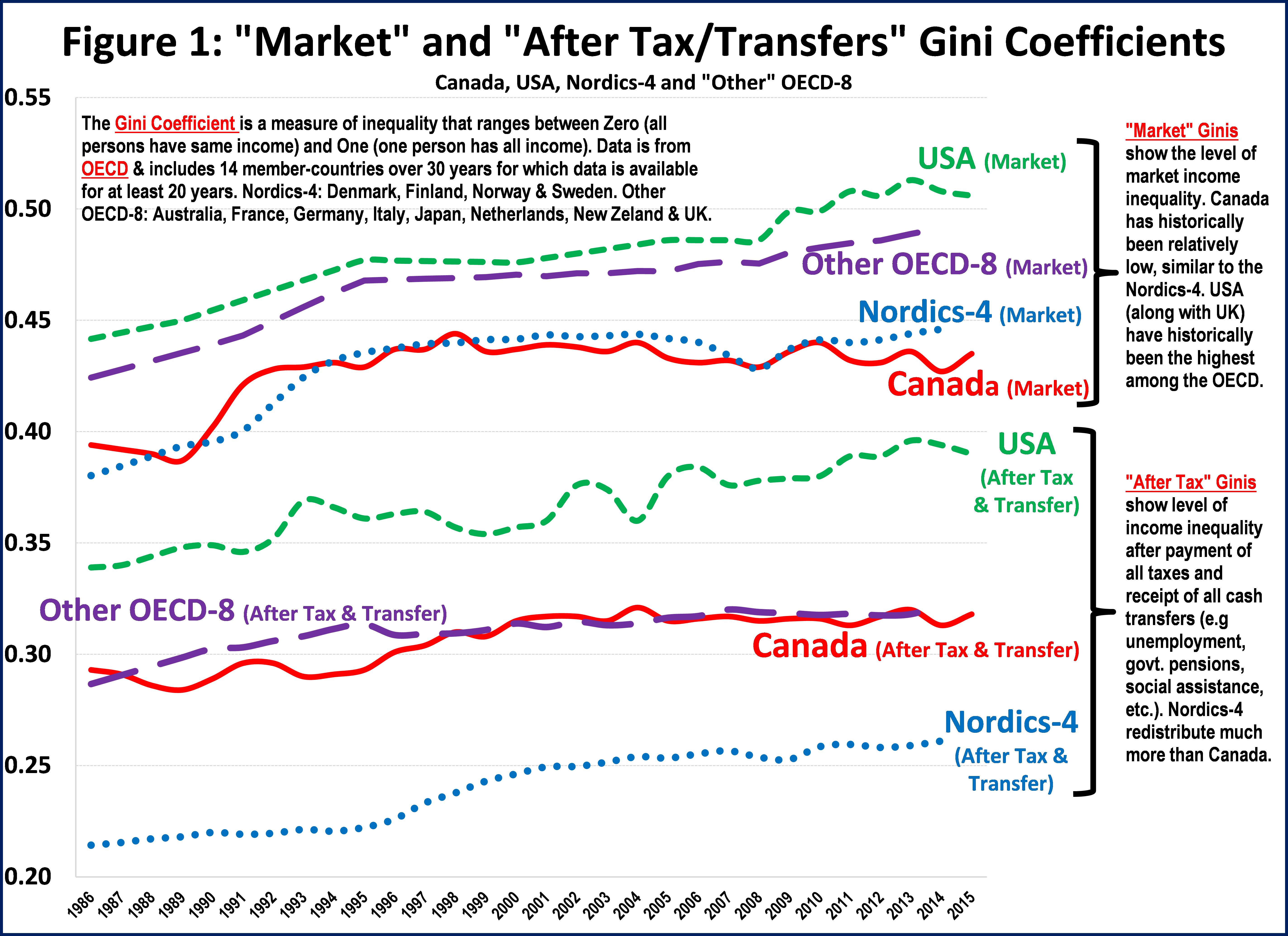

Figure 1 presents market and after-tax income Gini coefficients for Canada and selected OECD countries. Market income is before taxes and government cash transfers, while after-tax income is after such taxes and transfers. The Gini coefficient varies from 0 to 1.00, with higher values representing higher inequality. Figure 1 includes data on the USA, the four larger Nordic countries (“Nordics-4”): Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) and the other eight OECD countries for which data are available from the mid-1980s (“Other OECD-8”: Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand and UK). I have annotated Figure 1 to explain these inequality-related concepts and data. Focusing on the last few years (readers can refer to the earlier blog for a longer-term analysis), Figure 1 shows a general continuation of recent trends. Market inequality in the Other OECD-8 and Nordics-4 has continued to increase, while the long-running economic expansion in the USA appears to have finally (and perhaps only temporarily) paused the long-term increase in market inequality in that country. Canada continues to have relatively low market inequality and average after-tax inequality.

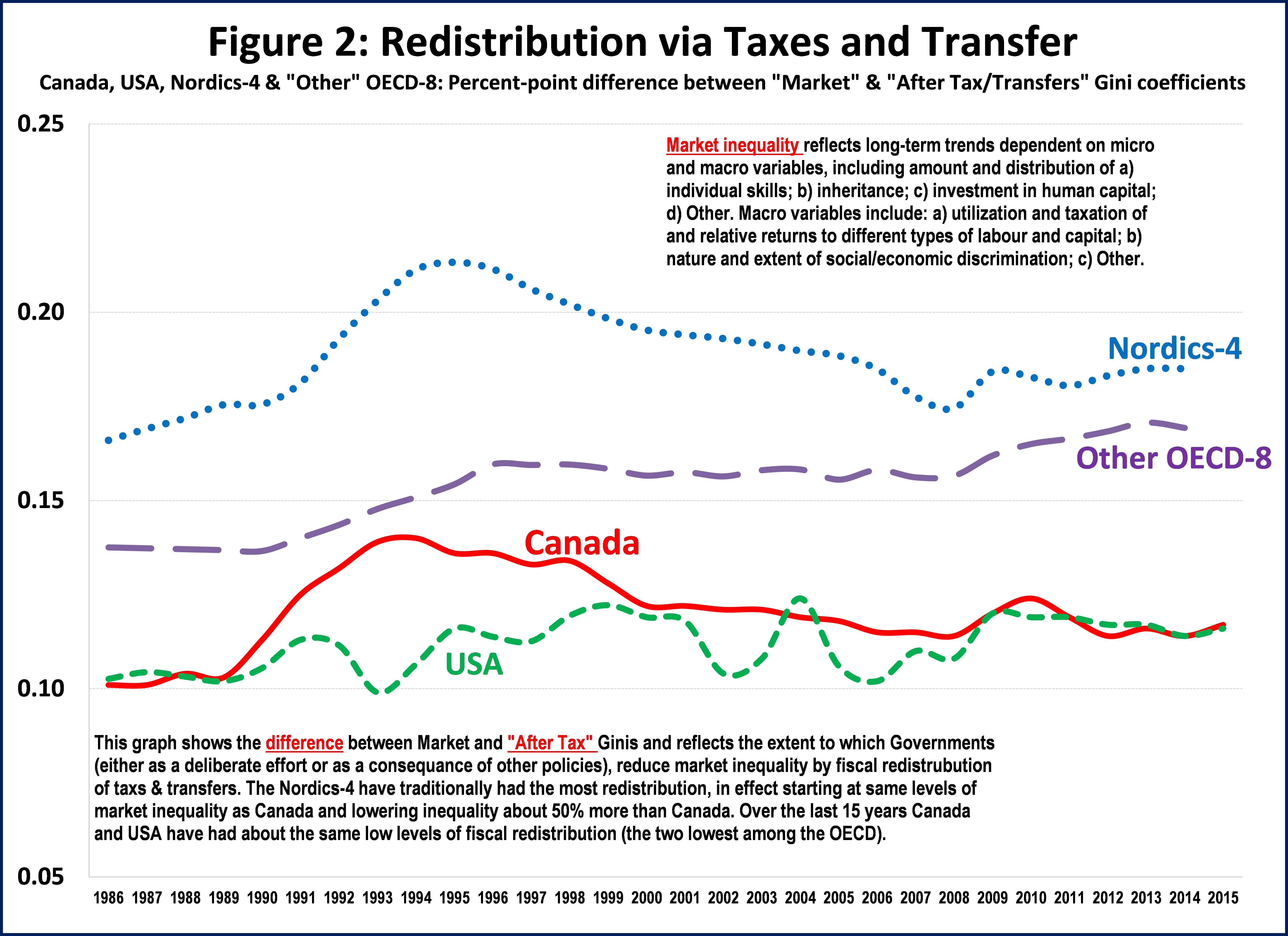

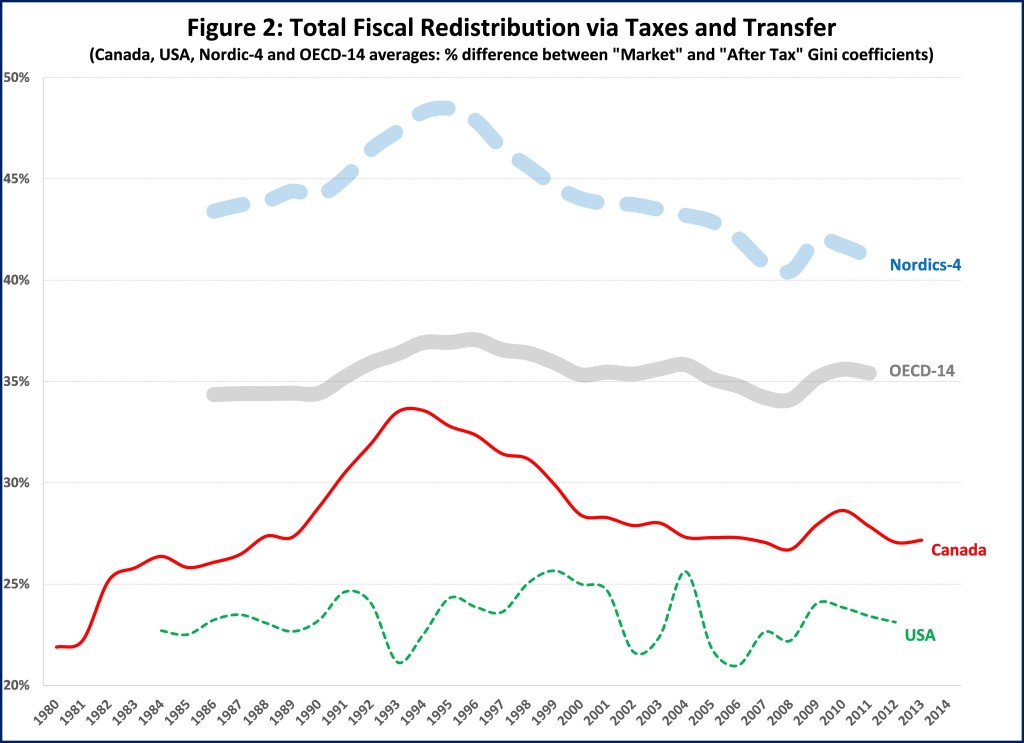

Figure 2 shows the percentage point difference between market and after-tax income Gini coefficients and reflects the extent to which Governments reduce market inequality by taxes and cash transfers. The Nordics-4 have traditionally had the highest level of such redistribution, currently lowering inequality by about 50% more than Canada does. Over the last decade Canada and the USA have had about the same low levels of redistribution (the two lowest among the OECD).

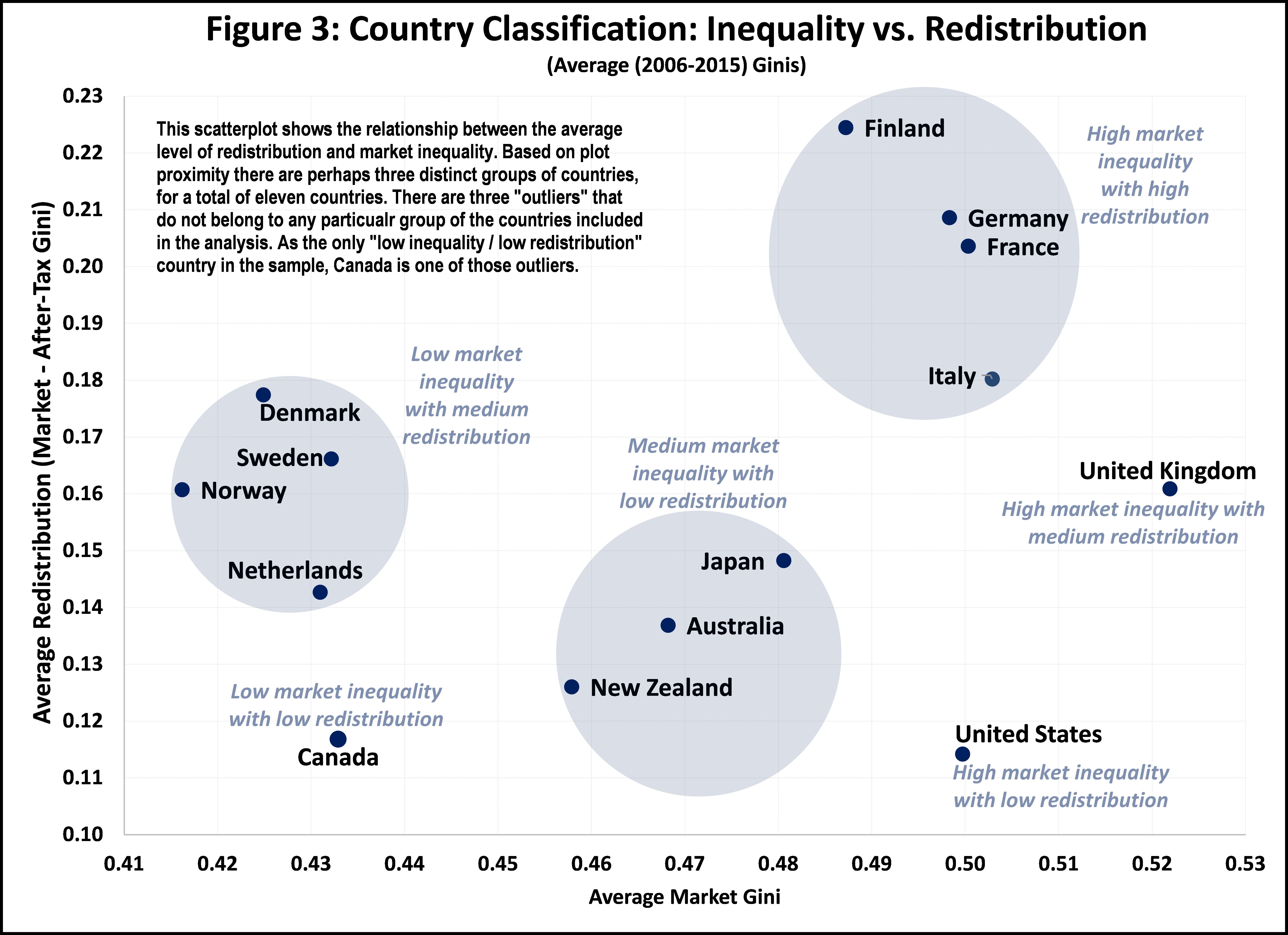

Figure 3 shows the political-economy outcome of the market inequality-redistribution relationship. For each of the 14 OECD countries listed above, Figure 3 includes average market inequality plotted against average redistribution (as measured above). Figure 3 appears to include three distinct “clusters” of countries:

- Low market inequality with medium redistribution, including Denmark, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

- Medium market inequality with low redistribution, including Australia, Japan and New Zealand

- High market inequality with high redistribution, including Finland, France, Germany and Italy.

These three clusters include a total of eleven countries, leaving three “outliers” that do not belong to any particular cluster. Canada is one of these outliers, being the only “low inequality / low redistribution” country. Others are the USA (high market inequality with low redistribution) and the UK (high market inequality with medium redistribution).

Each country’s inequality-redistribution outcome is the result of a series of complex national political-economy interactions. The cluster analysis in Figure 3 shows, however, that international and regional influences also matter. It is perhaps not surprising that Australia and New Zealand are in the same cluster, as is Japan. The “Nordic” cluster (including Netherlands but excluding Finland) could also be expected given proximity and historical ties. France and Germany being in the same cluster is also consistent with this hypothesis. That the UK is an outlier is perhaps not surprising (e.g. Brexit, etc.). The USA has always followed its own path and therefore is also a high inequality / low redistribution outlier.

Which brings us to Canada, another outlier, the only low inequality/low redistribution country. It has maintained Nordic-type levels of low market inequality via the public provision of universal human-capital-enhancing programs (e.g high quality health care, education, etc.), while implementing only USA-type levels of redistribution. Current political battles and outcomes related to the minimum wage, taxes and social assistance indicate that market inequality-reducing measures (e.g. minimum wage, etc.) continue to be more politically-feasible than those that increase redistribution and reduce poverty outcomes (e.g. more progressive taxation, increased social assistance, etc.). While fighting to maintain and expand universal social programs, progressives should work harder to prepare the political ground for Canada to increase redistribution, especially for when market inequality increases.

2. 2016 년:

Redistribution, Inequality, and Federal Policy: Guest Post by Edgardo Sepulveda

Posted by Jim Stanford under child benefits, fiscal federalism, income distribution, income tax, inequality, liberals, taxation.

January 20th, 2016

Comments: 3

We are pleased to present this rich guest post by a new PEF member, Edgardo Sepulveda. Edgardo has been a consulting economist for more than two decades advising Governments and operators in more than 40 countries on telecommunications policy and regulation matters (www.esepulveda.com).

Redistribution, Inequality and the new Federal Tax & Transfer initiatives

I want to present an analysis of Canada’s taxation and transfers system from a historical and international perspective, focussing on how changes in Canada’s fiscal redistribution over the last two decades have increased after tax income inequality. I also situate three of the new Federal Government’s proposed initiatives: the “middle class tax cut†(“MCTCâ€), the new Canada Child Benefit (“CCBâ€); and increases to GIS benefits in this broader context. This work brings together several elements that have been discussed here and in other research, and updates the analysis based on recently-released internationally-comparable data from the OECD.

Analysis

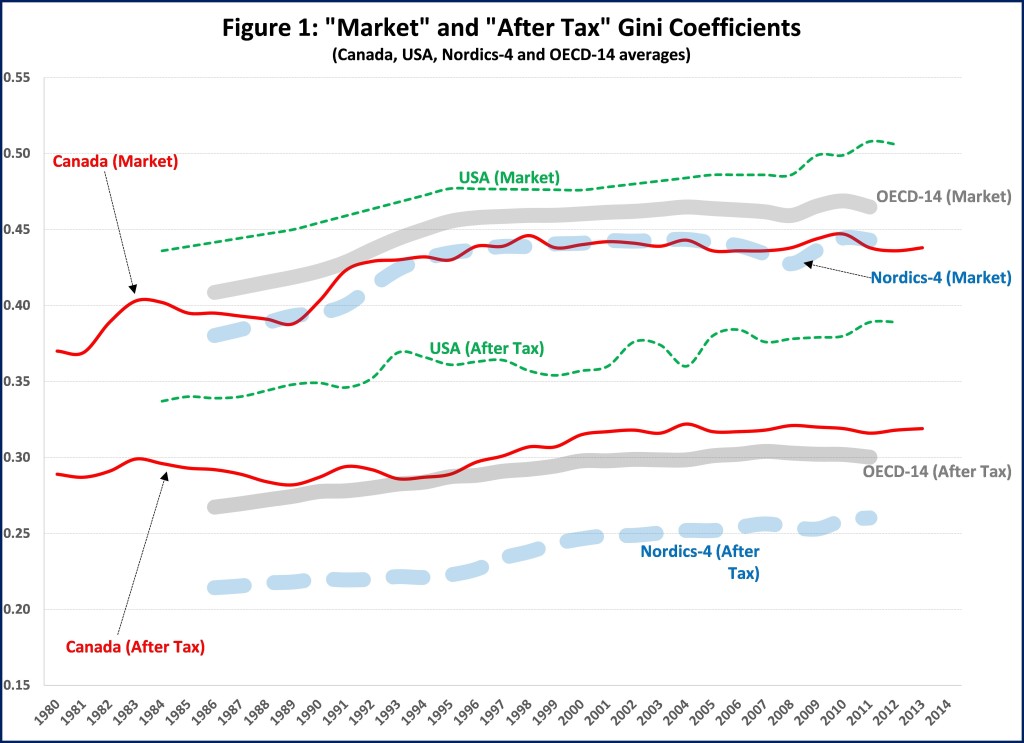

Figure 1 presents “market†and “after tax†income Gini coefficients for Canada and the OECD. Market income is before taxes and government cash transfers, while after tax income is after taxes and transfers. The Gini coefficient varies from 0 to 1.00, with higher values representing higher inequality. For comparative purposes, I include the “OECD-14†(representing the 14 OECD Member-Countries for which Gini coefficients are available from the mid-1980s) average, as well as the traditional inequality/taxation revenue “book-endsâ€: the USA and the four larger Nordic countries (“Nordics-4â€: Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden).

Figure 1 shows that market income inequality generally increased relatively quickly until the mid-1990s, after which it slowed down or stabilized across the OECD-14. Canada’s market inequality is below the OECD-14, similar to that of the Nordics-4 and lower than the USA. Governments redistribute income via the tax and transfer systems (“fiscal redistribution†or “redistributionâ€) and hence after tax income Gini coefficients are always lower than the respective market income Gini coefficients.

Fiscal redistribution varies significantly across time and countries. For example, Canada has historically had lower market inequality than the OECD-14, but has historically had higher after tax inequality. Similarly, Canada has had market inequality comparable to the Nordics-4, but has historically had much higher after tax inequality. One way to measure redistribution is presented in Figure 2, which shows the percentage difference between market and after tax income Gini coefficients. For example, Canada’s figure of 34% for 1994 indicates that redistribution reduced market to after tax inequality from 0.432 to 0.287. Figure 2 confirms that Canada (currently at 27%) has traditionally had less redistribution than the OECD-14 (currently at 35%) and the Nordics-4 (currently at 41%) and that its redistribution has decreased since peaking in 1994. Redistribution in Canada has been closer to the USA (currently at 23%) for more than a decade.

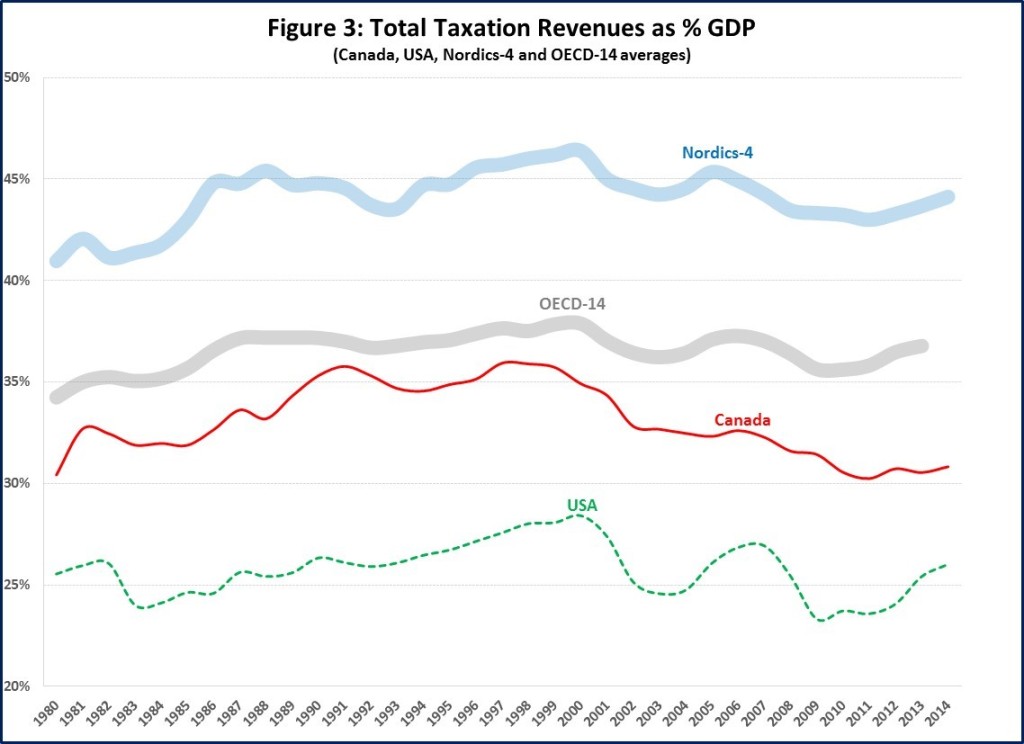

A country’s redistribution is a combination of its fiscal capacity and allocation of revenues and expenditures. Figure 3 presents total (“all Governmentâ€) taxation revenues as a percentage of GDP and shows a steady increase and subsequent stabilization until about the mid/late 1990s for Canada, the OECD-14 and the Nordics-4, at around 35%, 37% and 45%, respectively (the USA is an outlier at around 25%). Figure 3 shows that Canada’s taxation revenues to GDP started to decline in the late 1990’s so that by the 2010s Canada had stabilized at around 30%-31%; Canada is now closer to the USA than the OECD-14 and is at its lowest level since 1980.

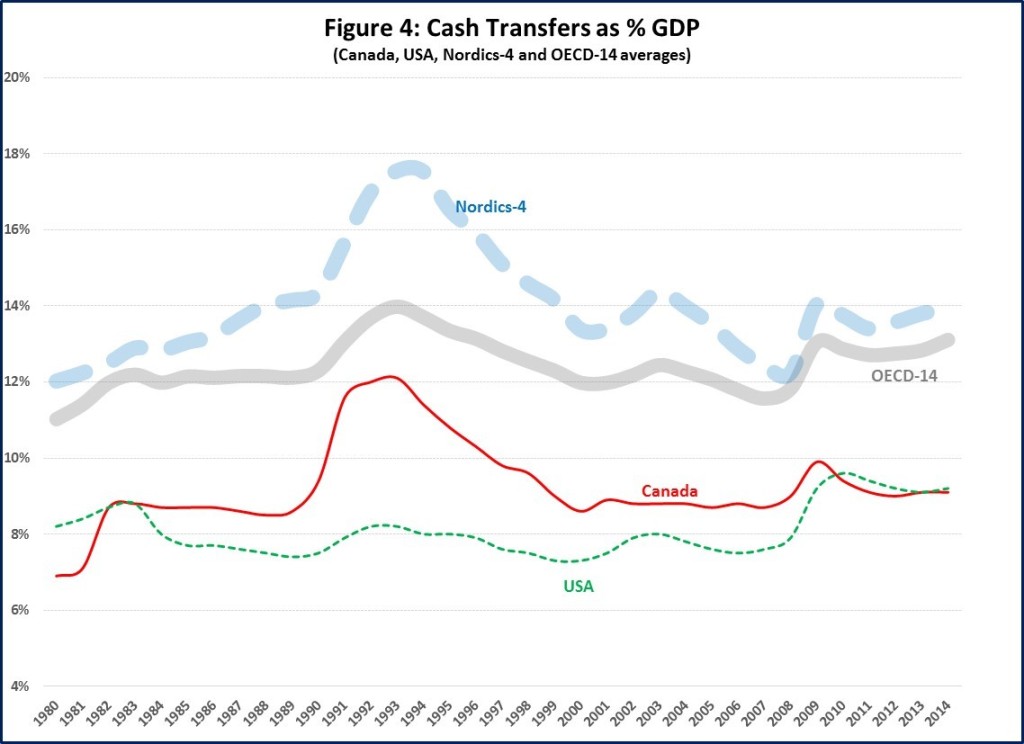

Research has shown that transfers have generally accounted for about two-thirds of the redistributive impact, with taxes accounting for the other third. Personal income tax (PIT) revenues to GDP in Canada have been historically similar to those in the OECD-14, and hence cannot explain the differences in redistribution. In fact, Figure 4 shows that these differences are due to transfers; Canada has historically had lower transfers to GDP than the OECD-14. Since 1980, the OECD-14 have on average allocated 34% of total taxation revenues to transfers, while Canada has averaged 28%. Taken together, Canada’s relatively low and decreasing taxation revenues to GDP and its low allocation to transfers have led to comparatively low and decreasing transfers, resulting in low and, and since 1994, decreasing redistribution.

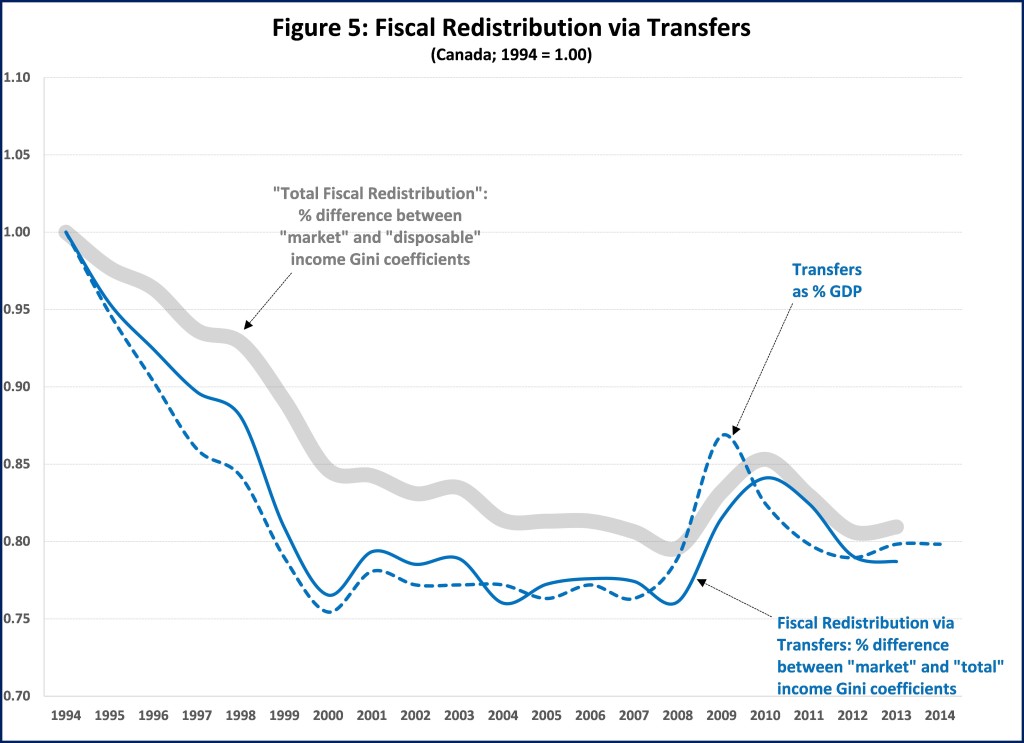

The next two figures separate the effect of taxes and transfers on redistribution since it peaked in 1994. This more disaggregate analysis is possible for Canada because Statistics Canada also makes available the “total†income Gini coefficient (not available from the OECD), which is the market income plus transfers, but before taxes.

For Canada, Figure 5 brings together the changes in transfers to GDP with the transfers component of redistribution. Figure 5 also includes total redistribution (all numbers indexed to 1.00 in 1994). Figure 5 shows that transfers to GDP and transfers redistribution are closely correlated and have stabilized at between 20%-25% below the 1994 peak: decreased transfers lead to less redistribution. Transfers redistribution decreased more than total redistribution. The redistributive impact of any fiscal variable may be disaggregated between the size and the progressivity of the variable. The close relationship between transfers and transfers redistribution suggests that it is primarily the size of transfers that has changed since 1994 (with only modest changes in progressivity). In effect, other research indicates that the main drivers of this overall reduction were decreases in the “size†of provincial social assistance (SA) and federal Employment Insurance (EI) relative to GDP.

Figure 6 presents the equivalent data for the taxation component and shows that both PIT revenues to GDP and the tax redistribution increased from 1994 to 1999 (higher taxes led to greater redistribution), after which they generally decreased (lower taxes led to less redistribution). Figure 6 shows a relatively close relationship between the two variables over the 1994-1999 period, but less so during the 2000-2014 period, with PIT decreases not resulting in commensurate increases in inequality, suggesting that the progressivity of PIT increased somewhat during this period.

Discussion

Canada’s tax and transfers have historically provided less fiscal redistribution than almost all our OECD-14 counterparts. Most of the difference in this performance is due to Canada’s low and declining transfers, which together with lower personal income taxes, has led to higher after tax income inequality in Canada over the last two decades. This is in spite of underlying market income inequality being relatively stable over this period. In almost all these respects Canada has diverged from the OECD-14 and converged to the USA over the last two decades.

Such changes in fiscal redistribution are policy-induced and therefore subject to change. I have shown that other OECD-14 counterparts have achieved and maintained much higher redistribution and lower after tax income inequality.

This analysis identifies a number of broad policy options to increase redistribution, which I also use to situate and discuss the new Federal Government’s three proposed initiatives.

·        One policy option is to increase the progressivity of taxes and/or transfers. The MCTC is a good example of this, in that it re-allocates about $3 billion of PIT around the upper income distribution while (more or less) being “revenue neutralâ€. The MCTC is therefore modestly progressive but its relative “size†is very modest (accounting for less than 2% of PIT revenues), so I expect its redistributive impact will be very modest.

·        A second policy option is to increase the size of taxes and/or transfers. The increase of about $0.7 billion in GIS benefits is a good example of this. This proposed initiative may be expected to be relatively progressive, but its relative size is very modest (accounting for less than 1% of Government cash transfers), so its redistributive impact will also be very modest.

·        A third policy option is to combine an increase in the size and progressivity of taxes and/or transfers. The new CCB is a good example of this because it eliminates three existing child benefits (about $18 billion + $2 billion from income splitting elimination) and combines them into a new $22 billion CCB (with an additional $2 billion) (therefore a net increase of $4 billion), that is designed to be somewhat more progressive. I expect that the CCB will have a modest redistributive impact.

All three Federal Government initiatives will increase redistribution and will therefore reduce after tax income inequality. As possible future work I may try to model the redistributive impact of these three initiatives. Based on the analysis above and other research, my current “back of the envelope†estimate is that, ceteris paribus, when fully implemented, the combined redistributive impact of the three initiatives would decrease Canada’s after tax Gini coefficient by perhaps up to 0.005 points and thus increase Canada’s redistribution perhaps by one percentage point – that is, from the current 27% to perhaps about 28%. These initiatives are therefore relatively very modest and would constitute only first steps in a long process towards returning Canada’s redistribution to prior levels (peak of 34%) or those that are comparable to most of our OECD-14 counterparts (currently at 35%), let alone the Nordics-4 (currently at 41%).

Of course, given Canada’s system of fiscal federalism, the Provinces would also have to do their part. The Provinces together collect PIT revenues that are comparable to those of the Federal Government, receive transfer payment from the Federal Government intended for social programs (the Canada Social Transfer (CST)) and are also responsible for important transfers, including social assistance (SA); hence have both the fiscal capacity and the tools to increase redistribution. As noted above, the size of SA relative to GDP has decreased considerably since the mid-1990s. Using the same “back of the envelope†methodology, I estimate that for the Provinces to “match†the one percentage point redistribution increase from the Federal Government’s three initiatives, they would have to, for example, increase the “size†of SA by perhaps in the range of $5-$6 billion in total. Such an increase could be through some combination of broadening the eligibility criteria or increasing the amount of cash benefits.

'정치경제' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 박수환과 우병우 문자교환을 보며: 박수환의 공범자들, 리먼브라더스 민유성 전 산업은행장, 대우조선 남상태, 우병우 (0) | 2019.02.14 |

|---|---|

| 법원이 윤석열을 두려워하는 이유 (0) | 2018.11.27 |

| [중국 전기차] 중국, 전기 자동차 생산, 정부가 추진, 화석연료 자동차 전부 대체하겠다 (0) | 2018.11.25 |

| 캐나다 알버타 주, 신민주당 NDP 일자리 창출 논쟁 (0) | 2018.11.03 |

| The 2018 living wage for Metro Vancouver is $20.91/hour (0) | 2018.11.03 |

| 양진호 자본 축적 방식, 불법 동영상 1160만에게 팔아 3년간 400억 이익 (0) | 2018.11.03 |

| 위디스크 양진호 사장, 직원들 폭행, 불법 자본 축적, 검찰 정치권 매수했는가? (0) | 2018.11.03 |