인류 최초의 집. 180~200만년 전 분데벡 동굴.

360만년 전 오스트랄로피테쿠스는 여전히 나무에 거주.

이 동굴 거주자는 호모 하빌리스 Homo Habilis.

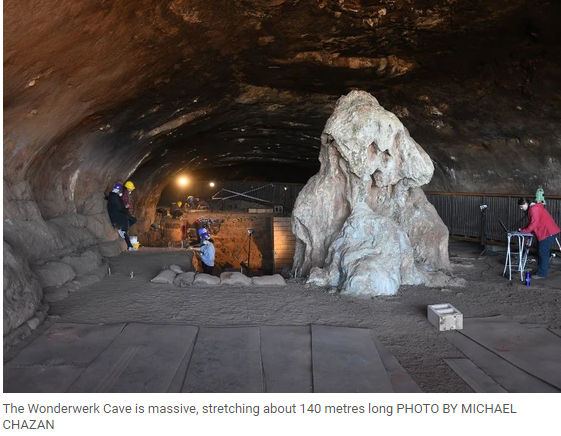

140 미터 ,폭 11~26 미터, 백운석으로 된 분더벡 동굴. 남아프리카 공화국.

인류조상 호미닌의 동굴 생활 추적.

발견된 유물. 구석기 도구. 뼈 파편. 불탄 잔디, 나뭇잎.

1940년대 농부들이 이 분데벡 동굴을 발견한 후, 지금까지 발굴이 계속되고 있다.

왜 이런 어두운 동굴에 와서 살았는가? 1)가설. 다른 동물 공격으로부터 피하기 위해

2) 가설. 텔 아비브 대학 란 바르카이 교수의 가설. 불을 피우고 저산소증으로 인한 '환각' 현상 발생.

불을 어떻게 사용했나?

호모 하빌리스가 자연발생적인 '불', 불탄 나무가지를 동굴로 가져왔을 수도.

동굴안 퇴적물의 지층들 연대 추적 2가지 방식.

1) paleomagnetism (옛날 땅의 자기를 밝히는 연구. 고지자기-古地磁氣, 고지자기학(學). 동굴 공기 중에 점토 입자들로부터 자기 신호를 측정함.

시간대별로 포착된 이 신호들을 분석해보면, 지구 자기장의 방향을 알 수 있다.

백년 단위로 이런 자기장의 변동과 전복 과정을 차트로 그리면서, 동굴 속 점토 입자와 그 속에 들어있는 모든 것의 연대를 측정할 수 있다.

2) 두번째 방법. 매장 연도를 사용. 입자들이 우주 방사선 빛으로부터 쫘악 퍼지다가 지하에 묻히고,이 경우는 동굴 속에 파묻혔을 때, 그 점토 입자의 방사성 붕괴를 분석.

모래 석영 입자는 ‘내장된 지질학 시계’이다. 왜냐하면 그 입자가 동굴 안으로 들어가는 순간부터 그 시계가 작동하기 때문이다.

올두바이 도구 (초기 구석기 도구) 사용을 180만년 전으로 거슬러 올라가고, 이것보다 더 복잡한 손도끼 사용을 100만년 보다 더 이전이라고 봐야 한다. 그리고 자연적이고 우발적인 ‘불’이 아니라, 의도적인 불의 사용 시기는 약 100만년 전이라고 추정할 수 있다.

분데벡 동굴 안에 퇴적물의 지층들처럼 인간 활동의 기록들을 일관되게 잘 보관하고 있는 곳은 드물다. 분데벡 동굴 안에 퇴적물의 정확한 나이를 밝혀내면, 호미닌 (인류조상)의 생물학적 문화적 진화 과정에서 결정적인 사건들의 시기가 해명될 것이다.

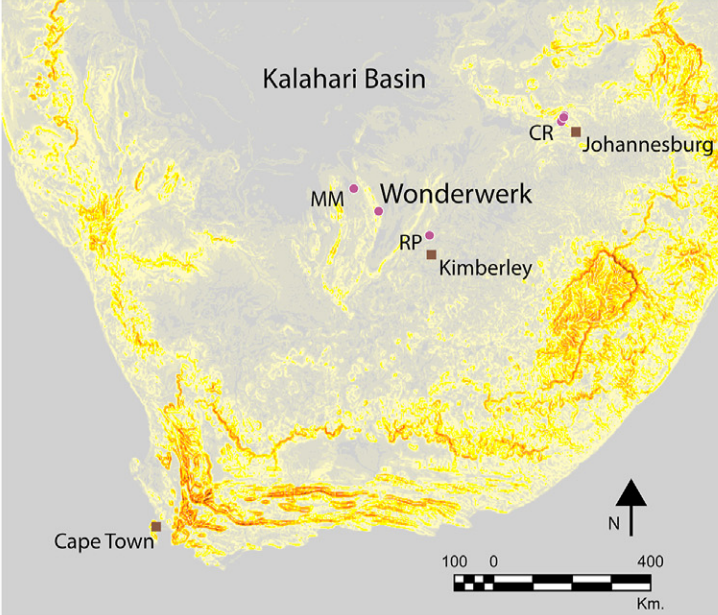

분더벡 동굴. (Wonderwerk cave.) 남아공. 크루먼 언덕.

칼라하리 유역 Kalahari Basin 칼라하리 베이신.

Oldowan 올두바이. 200만년~150만년 아프리카. 초기 구석기 문화 지칭. 호모 하빌리스가 쓰던 원시 석기 도구.

Paleomagnetism 팰리오 마그네티즘. . 고지자기-古地磁氣, 고지자기학(學)

Radioactive Decay 방사선 붕괴.

석영 입자. Quartz particles.

묘지(crypt) 만 발견된다면, 고고학자들에게는 '잭팟'을 터뜨리는 것과 마찬가지라고 함. 그 결과는 아직 모름.

Scientists Find Oldest Evidence of Ancient Human Activity Deep Inside a Desert Cave-

DAVID NIELD - 30 APRIL 2021

The Wonderwerk Cave site in South Africa is one of very few places on Earth where human activity can be traced back continuously across millennia, and scientists just established the oldest evidence of archaic human habitation in the cave: some 1.8 million years ago.

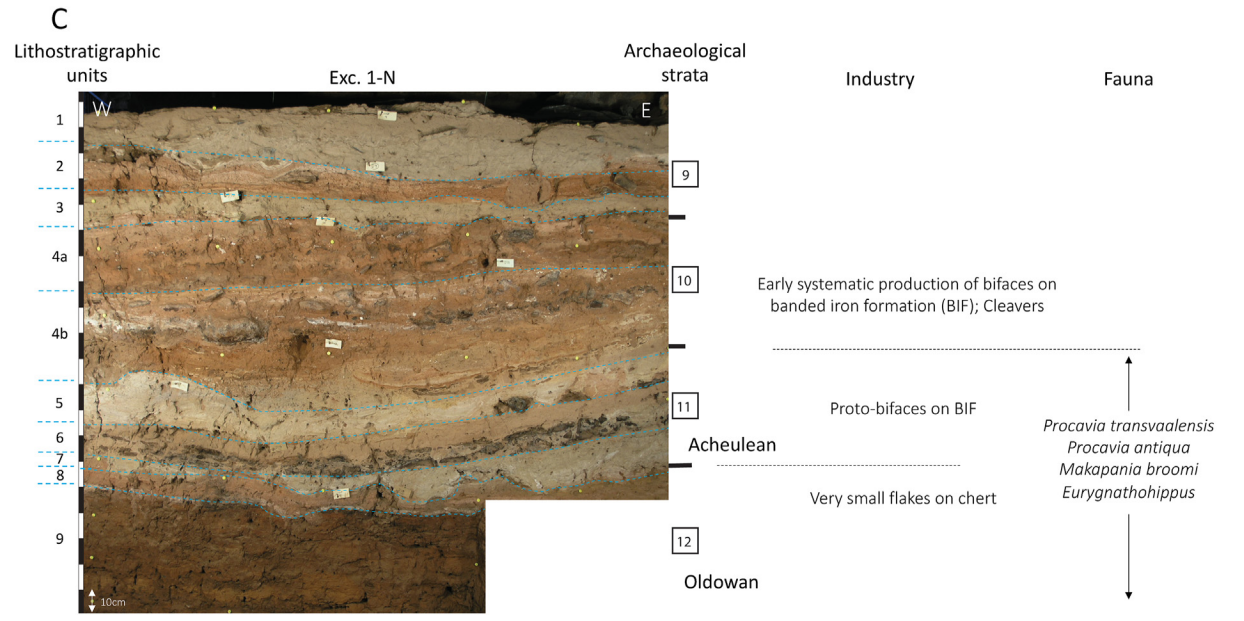

That's based on an analysis of sedimentary layers containing animal bones, the remnants of burning fires, and Oldowan stone tools: Objects made from simple rocks with flakes chipped off to sharpen them, representing what was once a significant step forward in tool technology.

While tool artifacts at other sites have been backdated as far as 3.3 million years ago, the new findings are now thought to be the earliest sign of continuous prehistoric human living inside a cave – with the use of fire and tools in one fixed location indoors.

cave 2

The Kalahari desert Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

"We can now say with confidence that our human ancestors were making simple Oldowan stone tools inside the Wonderwerk Cave 1.8 million years ago," says geologist Ron Shaar from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

"Wonderwerk is unique among ancient Oldowan sites, a tool-type first found 2.6 million years ago in East Africa, precisely because it is a cave and not an open-air occurrence."

While ancient evidence of wildfires and human fires might get mixed up in open-air sites, that's not the case in the Wonderwerk Cave. What's more, other indicators of humans making fires were found: burnt bones and ash, for example, as well as the tools.

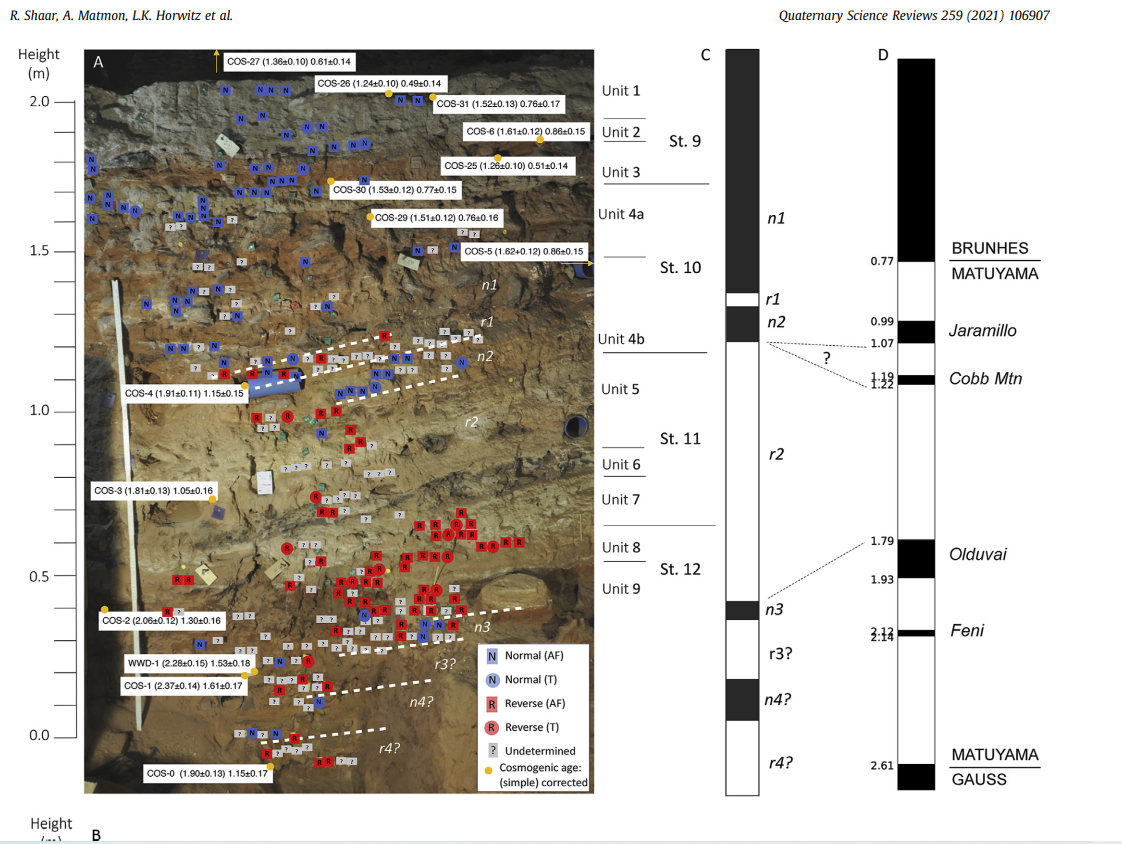

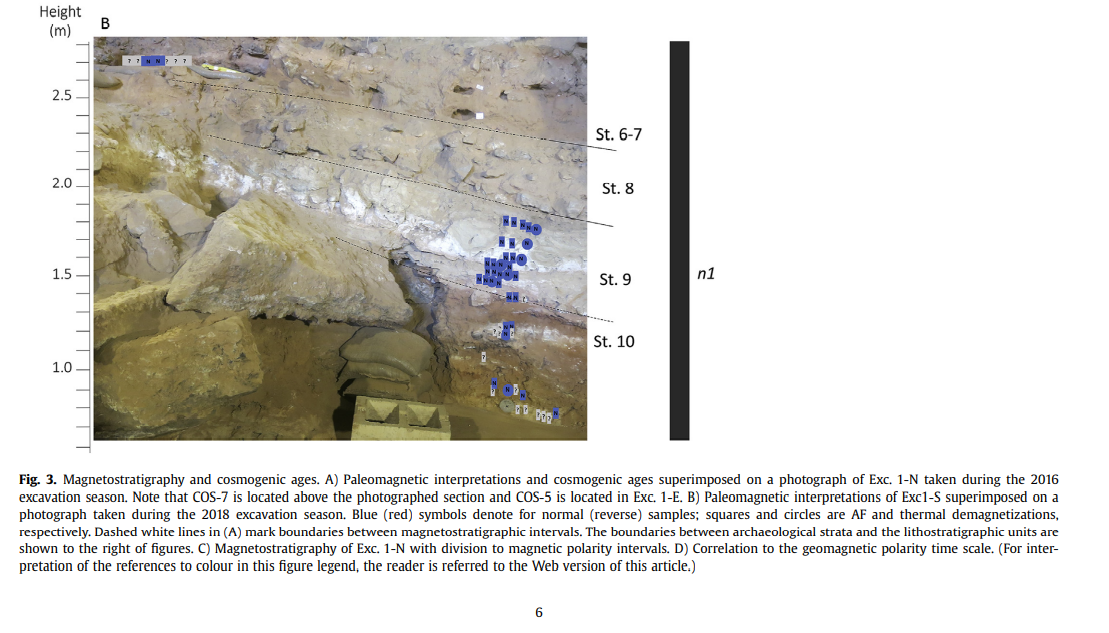

The sediment sample examined in the new study was 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) thick, charting hominin activity in the cave over time. Layers were dated in two ways, first through paleomagnetism, measuring the magnetic signal from clay particles that had drifted into the cave.

These signals, trapped in time, show the direction of Earth's magnetic field in history. As the variation and flipping of this field across the centuries can be charted, scientists can date the clay particles and everything deposited with them.

Secondly, the researchers used burial dating, an analysis of the radioactive decay of particles as they drift out of the glare of cosmic radiation and get buried underground, or, in this case, inside a cave.

010 wonderwerk 1Inside the Wonderwerk Cave. (Michael Chazan/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

"Quartz particles in sand have a built-in geological clock that starts ticking when they enter a cave," says geologist Ari Matmon from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

"In our lab, we are able to measure the concentrations of specific isotopes in those particles and deduce how much time had passed since those grains of sand entered the cave."

As well as recording the use of Oldowan tools as far back as 1.8 million years ago, the team also spotted the transition to more complex hand axes (over 1 million years ago) and the first deliberate use of fire (around 1 million years ago).

While exciting discoveries continue to be made all across the world, very few places offer such a consistent record of ancient human comings and goings as the sediment layers inside the Wonderwerk Cave – as the new study shows.

"The precise ages of the Wonderwerk sediments are crucial for our understanding of the timing of critical events in hominin biological and cultural evolution in the region," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in Quaternary Science Reviews.

2. 기사.

Early Humans Lived in This South African Cave 2 Million Years Ago, Making It the World’s Oldest Home, Archaeologists Say

See photos of Wonderwerk Cave here.

Sarah Cascone, April 27, 2021

Excavations at Wonderwerk Cave have determined it was occupied by humans some two million years ago, making it the world's oldest-known home. Photo courtesy of Michael Chazan.

Archaeologists have identified Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa’s Kalahari Desert as the world’s oldest home, thanks to new evidence confirming the theory that early humans were already occupying the site 2 million years ago.

The dates for the cave—named for the Afrikaans word for “miracle”—were determined by testing the cave sediments, according to a new paper in Quaternary Science Reviews by researchers from the University of Toronto and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

“We can now say with confidence that our human ancestors were making simple Oldowan stone tools inside the Wonderwerk Cave 1.8 million years ago,” lead author Ron Shaar said in a statement.

Wonderwerk is “a key site for the Earlier Stone Age,” according to the paper, but archaeologists have never found human remains there. Instead, the dating was obtained by investigating the different rock laters, also known as the stratified sedimentary sequence, reports Haaretz.

Ron Shaar taking samples for paleomagnestisim at Wonderwerk Cave. Photo courtesy of Michael Chazan.

Ron Shaar taking samples for paleomagnestisim at Wonderwerk Cave. Photo courtesy of Michael Chazan.

The cave contains traces of basal sediment, produced by retreating glaciers grinding against the bedrock, which would have to have been tracked in by early humans.

Using magnetostratigraphy, a branch of stratigraphy that detects variations in the magnetic properties of rocks, the researchers dated 178 samples from the cave. Measuring the magnetic signal of these ancient clay particles revealed the direction of the earth’s magnetic field—which changes poles every half million years or so—when the dust first entered the cave.

“Since the exact timing of these magnetic ‘reversals’ is globally recognized, it gave us clues to the antiquity of the entire sequence of layers in the cave,” Shaar explained.

The findings dated some of the sediment to 2 million years old. That matched the results that study team member Michael Chazan reached using cosmogenic dating in 2008. That earlier research, which many scholars rejected, measured cosmogenic nuclides caused by exposure to cosmic rays, which are produced and decay at a known rate. The new study also used this technique as a secondary dating method.

Wonderwerk Cave. Photo courtesy of Michael Chazan.

“Quartz particles in sand have a built-in geological clock that starts ticking when they enter a cave,” Ari Matmon, another coauthor of the paper, added. “In our lab, we are able to measure the concentrations of specific isotopes in those particles and deduce how much time had passed since those grains of sand entered the cave.”

The cave also contains ancient stone tools such as hand axes, and the first evidence of early humans using fire, some one million years ago, as first reported in a 2012 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The evidence of the fire was found deep enough in the cave that it could only have been the result of human activity, not brought there by wildfire.

Though humans occupied the cave continuously over the last 2 million years, it was not discovered by modern humans until farmers came upon it the 1940s. Excavations have been ongoing ever since.

3.

관련 기사.

| Archaeology

Archaeologists Find Oldest Home in Human History, Dating to 2 Million Years Ago

Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa also houses the first known fire use, and another collection of useless crystals – but this one is half a million years old

Wonderwerk Cave, which stretches back 140 meters today but 150 meters two million years ago (or if a realtor is describing it).

Apr. 26, 2021

Archaeologists have found the oldest home in hominin history. Unsurprisingly, it is a cave: Wonderwerk Cave in the Kalahari Desert. Astonishingly, it has been occupied more or less continuously for two million years. Through most of that time, modern humans didn’t even exist.

In Wonderwerk Cave, archaeologists have found evidence that archaic humans lived inside the cave around 2 million years ago, the earliest-ever use of fire at a million years and earliest hand axes at over a million years, report Ron Shaar, Ari Matmon, Liora Kolska Horwitz, Yael Ebert and Michael Chazan in Quaternary Science Reviews.

How Bibi’s Jewish supremacists fanned the flames in Jerusalem. LISTEN

Two million years ago, our ancestors were still small-brained but were definitely bipedal. We don’t know when our ancestors left the trees and began to stride the Earth upright, but we seem to have begun to trade arborealism for bipedalism during our australopithecine phase. That began about 4 million years ago. The point at which we discovered the virtues of shelter is even murkier.

In fact, the purpose of the latest team, led by the geologists Shaar and Matmon, had been to validate the postulated 2-million-year-old timeline of the cave, and now that’s been done.

That said, it isn’t actually 100 percent clear which archaic humans lived in that cave. Not one smidgen of a single human bone, not one single tooth, has ever been found there in the near-century of the cave’s excavation, Horwitz tells Haaretz.

That may be because in contrast to, say, the Dead Sea Scrolls caves, this one is on ground level. You don’t have to climb down from a cliff top to get there; nobody went inside by accident, nor is it some out-of-the-way place to hide a body or two. Proto-hyenas on the other hand could get in easily. “The earliest excavators drove in and parked in the front of the cave,” Horwitz says. But for two million years, the hominins clearly used the cave and used tools there and dined there.

This is the earliest-known use of tools beneath a “roof,” rather than in the open air, the archaeologists explain.

Prehistoric DNA detected in caves reveals secrets of Neanderthal history

‘Rosetta stone’ fossil shows australopithecines still had apelike shoulders

Genetics cracks origins of two mysterious people: Scythians and Basques

Somebody in the Kalahari had a crystal collection 105,000 years ago

Walking the walk

For all the recent discoveries regarding human evolution, much of our truly ancient history remains shrouded in murk. There were myriad types of archaic hominin in Africa and later in Eurasia as well; there seems to have been a lot of mixing; and we don’t know who our direct ancestors were, though we can make learned guesses.

We recently learned that the early australopiths living 3.6 million years ago had human-like feet on which they could stride. We also know they did walk upright, as we find from fossil trails. But they also had ape-like shoulders, indicating they had not abandoned the arboreal way of life; they could theoretically swing branch to branch, and australopithecine kiddies may even have retained primitive foot structure until maturity, enabling them to escape ground-bound predators by lurking in trees.

We also know that hominins were starting to make crude stone tools at least 3.3 million years ago, so the tools found in the Wonderwerk Cave are not the earliest known. But they are the earliest known to be found in the context of the cave life, Shaar explains to Haaretz. It is from his resampling of the cave that the validation of the dates is based.

The goal of the paper in Quaternary Science Reviews is actually to revisit the dating of Wonderwerk Cave, a deep cavern running 140 meters to its end. A rarity in that part of the Kalahari, the cave was discovered by farmers in the 1940s and has been under excavation more or less since then.

In 2008, archaeologists Prof. Michael Chazan of the University of Toronto and Horwitz reported it as the earliest evidence of cave-dwelling hominins. At the time, they thought all this dated to some 2 million years; others thought that nonsense. Now the dating has been validated.

At the time, they deduced that the oldest stone tools had been made and deposited in the cave by the hominins, as opposed to being washed in by flooding. That opinion has not changed, Shaar tells Haaretz.

Who actually lived there? There were multiple hominids in southern Africa at the time. Chazan and the team in 2008 surmised that the most likely tool-maker was Homo habilis.

Horwitz today is more cautious. "Many options and absolutely no clue in the cave," she says. "She points out that around 2 million years South Africa was home to at least two types of australopithecines, 2.3 million to 1.5 million years ago, and also early Homo. Says Horwitz: "We are placing a sure bet on early Homo, since we are not very adventurous gamblers."

The hypothesis of the baked hominin

Just this year we learned that somebody in the Kalahari was collecting useless junk 105,000 years ago – namely, crystals. They couldn’t have originated in the cave where they were found and nobody (today) could think what use they might have had. That was touted as the oldest collection of non-utile, non-functional stuff in the world, and hence to indicate symbolic thinking.

But somebody else in the Kalahari was collecting useless junk 500,000 to 300,000 years ago, Horwitz tells Haaretz. That was the oldest collection of non-utile, non-functional stuff in the world. She and Chazan wrote up the crystals in 2009 in World Archaeology.

In that paper, Horwitz and Chazan also address the properties of the depths of Wonderwerk Cave – why on earth would early hominins go that deep anyway, given that it would be pitch black? One possibility they suggest is that precisely because it was dark, the hominins could hide from predators there.

Another possibility is that the rear of the cave offered sensory experiences, and it was for that purpose – to get prehistorically blitzed – that the hominins ventured in that far. (Completely separately, Prof. Ran Barkai of Tel Aviv University and his team have demonstrated that fire use in the depths of narrow caves can lead to hypoxia, which can cause hallucinations.)

Supporting this hypothesis of the thoroughly baked hominin are the seemingly pointless crystals, augmented by some chalcedony pebbles, and ocher.

Why else might seemingly useless little stones be brought to the black depths of a cave? The cave is quite enormous, 140 meters in depth (let’s say) by over 25 meters in width, and these stones didn’t occur there naturally.

Open gallery view

Earlier Stone Age handaxe - background is the cave entrance

Early Stone Age handaxe - background is the Wonderwerk cave entranceCredit: Wonderwerk Cave Project

Among the signs of advanced cognitive ability, the archaeologists believe they have found indications that ocher may have been used there 500,000 to 300,000 years ago – hundreds of thousands of years earlier than thought.

"We have evidence for unusual symbolic activity in Wonderwerk dating around 400,000-500,000 years ago, which predates Middle Stone Age sites like Blombos [where early etchings have been found] –. People were sitting at the back of the cave, 140 meters from the entrance. They don't appear to have been making tools there," said Chazan. In the dark.

As for symbolic thinking and the ocher – use earlier than 300,000 years has been controversial; in Wonderwerk it seems to predate that, and may have been used half a million years ago.

Speaking of tools, this cave that keeps on giving, has also provided some of the oldest-known hand-axes in southern Africa, dating to well over 1 million years. Earlier hand-axes dating to 1.7 million years have been found in East Africa.

Also regarding our more immediate Middle Stone Age ancestors, Wonderwerk has more surprises up its sleeve. It isn't one of those caves that support the idea that our forebearers wined and dined on seafood, as shown at other sites clustered on South Africa's coast. It's inland, near the town Danielskuil amid the dry and sunbleached rocks of the Kuruman Hills and over 700 kilometers (435 miles) from the nearest beach.

Chazan points out that till recently, the thinking in archaeological circles had been that in the Middle Stone Age, the interior was arid and hominins clung to the coasts. But Wonderwerk clearly shows human activity in the cave 240,000 years ago, showing that the interior wasn’t that dry.

The hearth of the matter

For about half the two million years the cave was in use, it seems its occupants were warming themselves and/or possibly even barbecuing.

They may not have had control of fire in the sense that they knew how to ignite it but a million years ago, they were certainly using it. Burned bones, burned stones, burned soil and ash have been found 30 meters in from the cave mouth – which was probably at least 40 meters back when, Chazan explains to Haaretz. (The cave mouth would have eroded in all this time.) That's too deep inside the cave to have been caused by a wildfire, he explains.

The postulation is that they may have “harvested” fire, taking advantage of naturally caused bushfires, taking a burning twig back to the cave, and that sort of thing.

“We don’t have combustion features like at Qesem [Cave in Israel]. We’re talking about a burned patch, not a proper constructed hearth,” he qualifies. But it is nonetheless solid evidence of fire use a million years ago.

In time, modern humans evolved and so did rock art, and indeed Wonderwerk Cave has that too. It also boasts some of the earliest known “mobile art” in the world, meaning done on small rocks that could be carried about.

“These pieces of art can be dated because they are in situ in the archaeological layers,” Horwitz explains. Elsewhere in the Kalahari, surviving rock art is engraved or painted on large boulders or cave walls – also, however, the same subjects: animals, geometric forms and people.

As said, the cave isn't occupied today per se but it remains a spiritual place for local people, who associate it with a snake spirit. Given the total absence of actual hominin remains, Horwitz and Chazan do not shrink back from suggesting that the cave may have served a special purpose, even way back before modern humans even existed.

They point out that it's a rarity in its region, and also, that it would have been a landmark in the area since it features a great hulking stalagmite by its entrance –that goes back some tens of thousands of years. In Wonderwerk, the proto-human imagination predates even that towering monument of sedimentation by eons.

연구 논문.

2021_-_Ron_Shaar_-_MagnetostratigraphyandcosmogenicdatingofWonderwerk[retrieved 2021-11-25].pdf

4.97MB

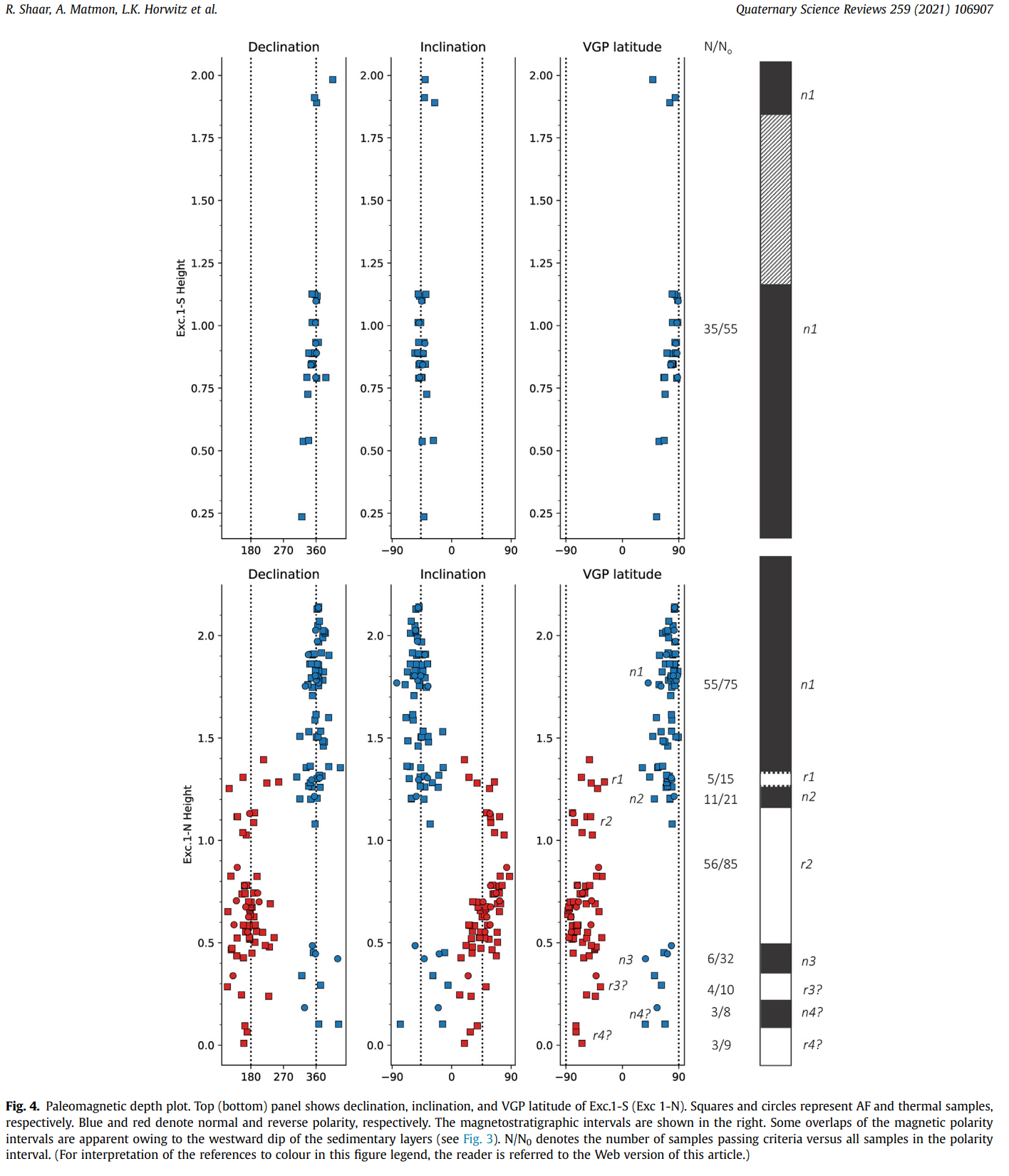

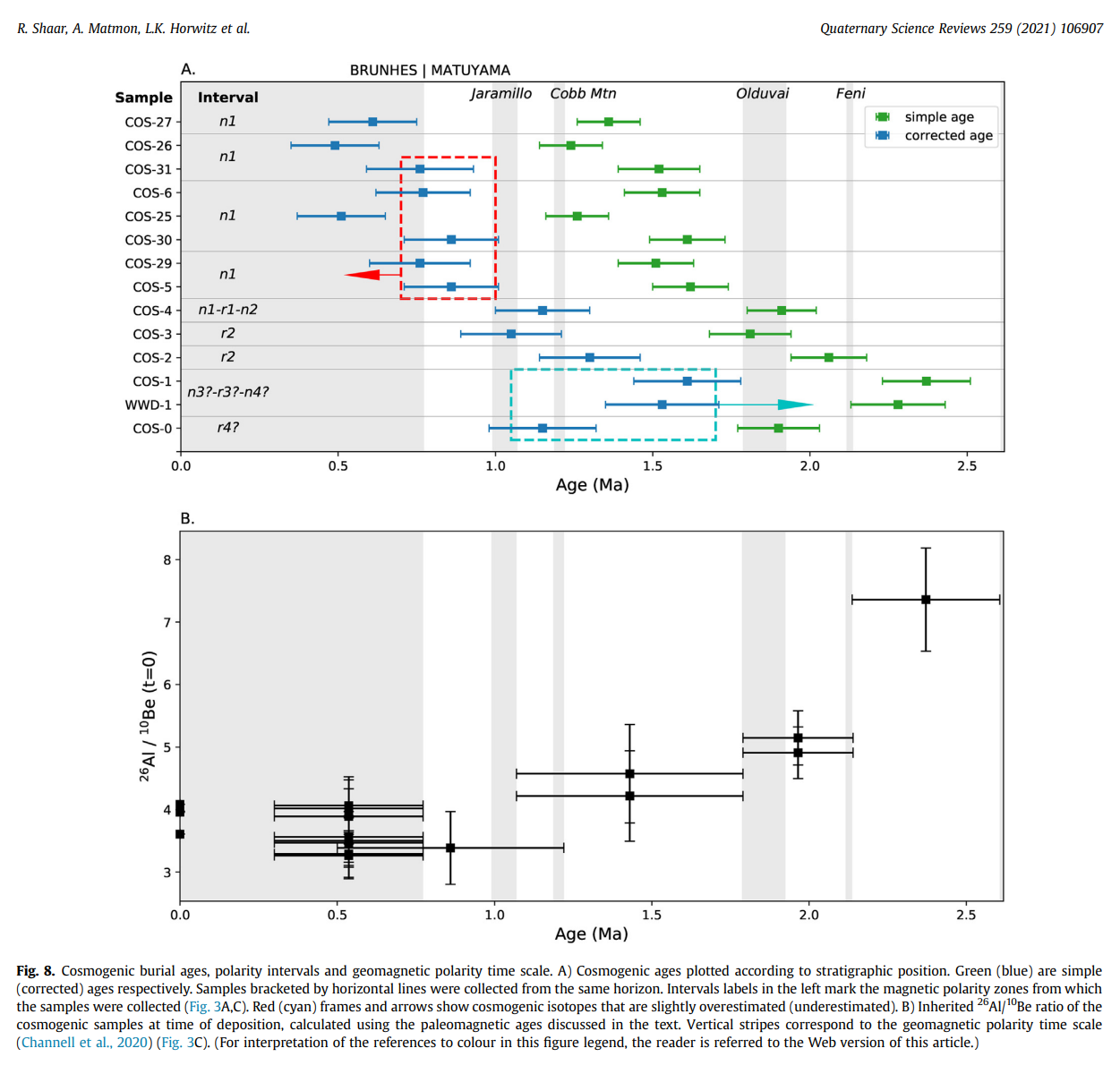

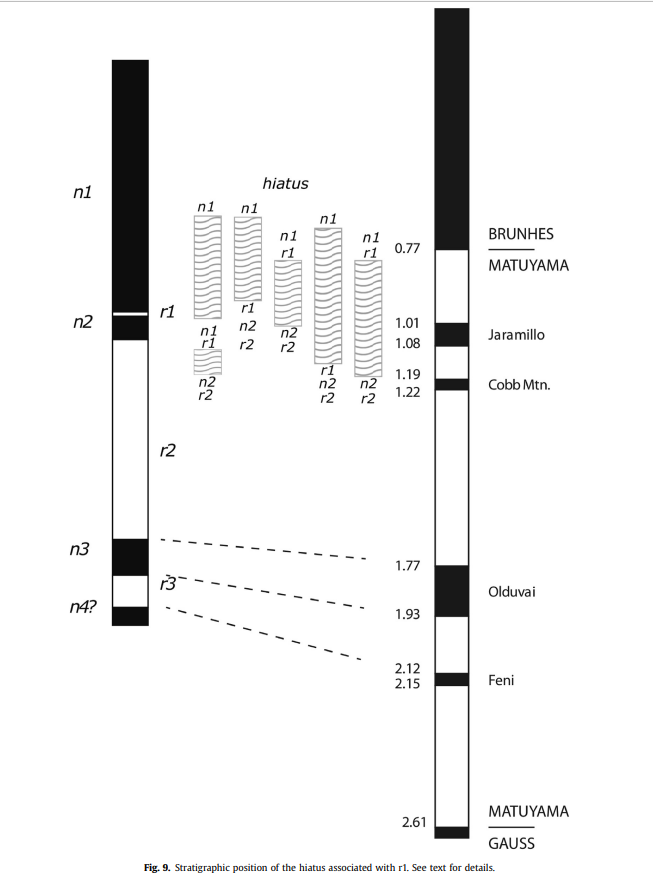

Cave sediments pose dating challenges due to complex depositional and post-depositional processes that

operate during their transport and accumulation. Here, we confront these challenges and investigate the

stratified sedimentary sequence from Wonderwerk Cave, which is a key site for the Earlier Stone Age

(ESA) in Southern Africa. The precise ages of the Wonderwerk sediments are crucial for our under-

standing of the timing of critical events in hominin biological and cultural evolution in the region, and its

correlation with the global paleontological and archaeological records. We report new constraints for the

Wonderwerk ESA chronology based on magnetostratigraphy, with 178 samples passing our rigorous

selection criteria, and fourteen cosmogenic burial ages. We identify a previously unrecognized reversal

within the Acheulean sequence attributed to the base of the Jaramillo (1.07 Ma) or Cobb Mtn. subchrons

(1.22 Ma). This reversal sets an early age constraint for the onset of the Acheulean, and supports the

assignment of the basal stratum to the Olduvai subchron (1.77e1.93 Ma). This temporal framework offers

strong evidence for the early establishment of the Oldowan and associated hominins in Southern Africa.

Notably, we found that cosmogenic burial ages of sediments older than 1 Ma are underestimated due to

changes in the inherited 26Al/10Be ratio of the quartz particles entering the cave. Back calculation of the

inherited 26Al/10Be ratios using magnetostratigraphic constraints reveals a decrease in the 26Al/10Be ratio

of the Kalahari sands with time. These results imply rapid aeolian transport in the Kalahari during the

early Pleistocene which slowed during the Middle Pleistocene and enabled prolonged and deeper burial

of sand while transported across the Kalahari Basin

자료.

2016_-__-_RevisitingtheParietalArtofWonderwerkCaveSouthAfric[retrieved 2021-11-25].pdf

2.63MB

David Morris.

Wonderwerk Cave, an exceptional archaeological site in

the South African interior, is an enormous 140-m deep

and 11–26-m wide dolomitic cavity in the side of the

Kuruman Hills (Figs. 1 and 2), containing deposits with

an archaeological sequence through Earlier, Middle and

Later Stone Age times, ca. 2.0 Ma to the recent past

(Humphreys and Thackeray 1983; Beaumont and Vogel

2006; Chazan et al. 2008; Chazan and Horwitz 2015;

Horwitz and Chazan 2015;

동굴 암석 종류. 백운암. 고회암. 돌러마이트. Dolomite Rock. 석회암과 약간 차이.

백운암(白雲岩) 또는 돌로스톤(Dolomite stone)은 결정질의 칼슘 마그네슘 탄산염 CaMg(CO3)2 으로 이루어진 퇴적 탄산염암이다. 백운암은 주로 백운석으로 이루어진다. 석회암 중에 일부가 백운석으로 치환된 것을 백운석질석회암이라 하며 과거 미국에서는 고(마그네시안)석회암이라 하였다.

백운암은 1791년 프랑스의 자연학자이자 지질학자였던 데오다 그라테 드 돌로미외(Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu, 1750-1801)가 북부 이탈리아의 돌로미티 알프스의 노두에 대해서 기술한 것이 처음이다. 이탈리아의 돌로미티에서 많이 발견된다.

. Dolomite (also known as dolomite rock, dolostone or dolomitic rock) is a sedimentary carbonate rock that contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2. It occurs widely, often in association with limestone and evaporites, though it is less abundant than limestone and rare in Cenozoic rock beds (beds less than about 65 million years in age).

The first geologist to distinguish dolomite rock from limestone was Belsazar Hacquet in 1778.

Most dolomite was formed as a magnesium replacement of limestone or of lime mud before lithification.

The geological process of conversion of calcite to dolomite is known as dolomitization and any intermediate product is known as dolomitic limestone.

The "dolomite problem" refers to the vast worldwide depositions of dolomite in the past geologic record in contrast to the limited amounts of dolomite formed in modern times.

Recent research has revealed sulfate-reducing bacteria living in anoxic conditions precipitate dolomite which indicates that some past dolomite deposits may be due to microbial activity.

Dolomite is resistant to erosion and can either contain bedded layers or be unbedded. It is less soluble than limestone in weakly acidic groundwater, but it can still develop solution features (karst) over time. Dolomite rock can act as an oil and natural gas reservoir.

'역사(history)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [펌] 자료 사진.초기 장로회 평양신학교 학생들과 교수들, Korea, 1905 (0) | 2022.02.14 |

|---|---|

| Der Rat der Volksbeauftragten, die neue Regierung, verkündet am 12. November 1918 das allgemeine, gleiche, direkte und geheime Wahlrecht auch für Frauen. (0) | 2021.11.29 |

| 전두환과 노태우의 차이 (0) | 2021.11.26 |

| 살인마 전두환의 장례식, 이한열 열사가 쓰러져 있던 연세 세브란스 병원에서 5일장을 한다는 게 말이 되는가? 분노와 수치이다. (0) | 2021.11.25 |

| 김대중 체포했던 이기동 중앙정보부 요원 증언 "전두환, 80년 5월18일, 남산 중정에서 직접 지휘했다" (0) | 2021.11.24 |

| "전두환이 잘못한 게 없다"고 주장한 민정기, 전두환 회고록 저자. 민정기는 누구인가? (0) | 2021.11.24 |

| 광주 항쟁 이후 2019년까지 피해자들 중 46명 자살. 전두환 일당은 감옥에서 죽었어야 했다. (0) | 2021.11.24 |