Shock therapy on the world economy- Michael Roberts

블로그

카테고리 이동

한국정치노트

검색 MY메뉴 열기

경제

미국 연방은행 기준 금리 인상 비판 이유. 인플레 원인은 개인과 정부의 초과 수요 때문이 아니라, 공급 부족이다.

프로필

nj원시

2022. 10. 18. 4:21

통계본문 기타 기능

Shock therapy 충격 요법 비판. Michael Roberts.

마이클 로버츠의 주장.

1. 미국 FRB 제이 포웰의 인플레 원인 분석이 오류다. 로버츠 견해는, 인플레 원인은 개인과 정부의 '초과 (과잉) 수요' 때문이 아니라, 공급 부족으로부터 발생되었다.

식량, 에너지 공급 부족.

제조업과 기술제품에서 저생산성

코비드 이후 생산과 유통에서 경색 발생.

러시아와 우크라이나 전쟁 발발로 에너지 공급 부족.

독일 분데스방크 나겔 (Nagel) 주장. 나겔은 단지 고금리를 원하지 않고, 유럽연합 중앙은행이 balance sheet를 축소하길 원한다. 단지 정부 채권을 매입 중단 (bond yield를 하락시키기 위해서) 하는 것 뿐만 아니라, 정부 채권을 매각해서 yield 를 증가시키려고 한다.

나겔 주장 “ 에너지 가격 충격에 대해서 유럽연합 중앙은행이 단기간 어떤 조치를 취할 수 없다. 그러나 통화정책 monetary policy을 통해 에너지 가격 충격의 파장이나 확대를 막을 수 있다. 금리 인상이라는 도구를 사용함으로써 인플레이션 다이내믹을 깨부술 수 있다 (헤쳐 나갈 수 있다) “

마이클 로버츠의 나겔 주장 “금리 인상을 통해서 인플레이션 통제가능하다”에 대한 비판.

유럽연합 중앙은행의 논리는 마초 macho 와 같고, 현실을 은폐한다. 금리인상을 통해 인플레이션을 목표 수치로 낮춘다는 것은 경기 침체를 동반하기 때문이다.

마이클 로버츠 주장. 최근 40년 인플레이션의 원인은 가계와 정부의 ‘초과 수요’가 아니라, 공급 부족이었다. 특히 식량과 에너지의 공급 부족과 제조업 상품과 테크놀로지 상품의 공급 부족이 인플레이션의 원인이었다.

주요 선진 자본주의국가들에서 성장의 둔화 원인은 생산성 증가 속도가 더뎠기 때문이다. 그리고 코비드 기간과 이후에 발생한 생산과 유통에서 공급 연결망의 경색이 발생했다. 이를 악화시킨 사건은 러시아와 우크라이나의 전쟁으로 인한 서방 국가들의 경제 제재이다.

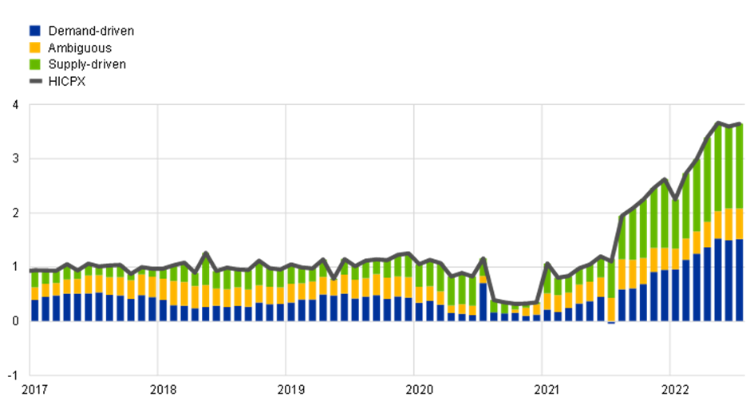

실제 경험적 조사에 따르면, 인플레이션 나선 spiral 은 공급-주도적이다.

유럽연합 중앙은행 조사에 따르면, (식량과 에너지 공급 요소를 배제한) 핵심 인플레이션 상승을 이끈 것은 ‘공급 경색(제약)’이었다.

“지속적인 산업 재화 공급 병목 현상, 투자 부족, 코로나 이후 노동력 부족 때문에, 급격한 인플레이션 (물가상승)이 발생했다. “ (유럽연합 중앙은행 보고서)

UNCTAD도 위와 동일한 진단을 최근에 발표했다.

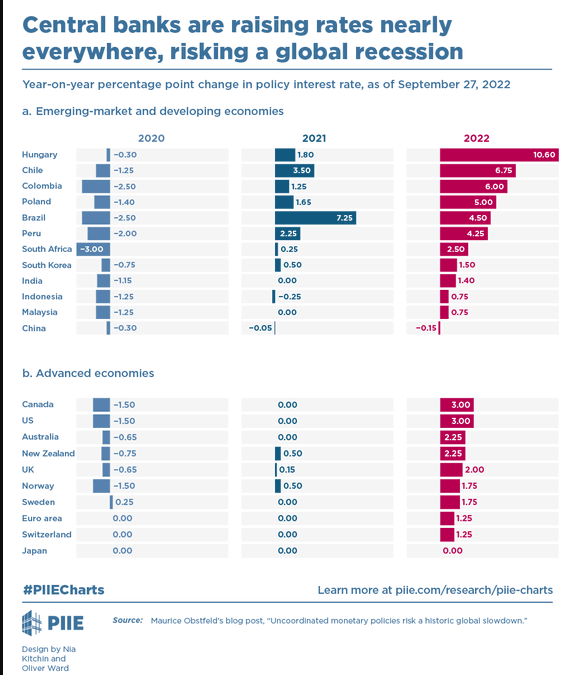

웅크타드 계산에 따르면, 미 연방준비제도 FRB가 1% 금리를 인상하면, 향후 3년간 선진국의 경우 0.5%, 개도국의 경우 0.8% 생산 감소를 불러일으킬 것이다.

만약 FRB 가 금리를 2%, 3% 인상시킨다면, 개도국 경제에 심각한 타격을 입힐 것이다.

UNCTAD 연구원. Richard Kozul Wright 주장과 비판. “지금 공급-측면 문제를 수요-측면 해법으로 해결하려고 하는가? 그렇다면 그것은 위험한 접근 방식이다.”

마이클 로버츠의 제이 포웰 Jay Powell 기준금리 인상에 대한 비판. - 노동자 임금 측면에서.

제이 포웰의 금리 인상은 wage-price spiral 에 대한 공포감의 표현이다.

제이 포웰의 논리에 따르면, 인플레이션이 발생한 후, 임금 노동자들이 이를 만회하기 위해서 임금 인상을 요구하게 되면, 이는 인플레이션을 더욱더 악화시키는다는 것이다.

마이클 로버츠의 FT 대표적인 케인지안 마틴 울프 Martin Wolf 논리 비판.

임금가격 spiral을 방지하고, 임금 상승을 억제하라. 이러한 마틴 울프의 논리는 실업율 증가를 방치하는 결과로 이어진다.

Bank of England. Andrew Bailey 논리도 동일.

이들의 주장은, 미시 경제의 기초 원리이다. 임금 상승이 인플레이션으로 이어진다.

과연 그러한가?

Karl Marx와 당시 노동조합주의자 Thomas Weston 간의 논쟁.

160년전 토마스 웨스턴은 노동자의 임금인상이 자기 반박적이라고 주쟁했다. 노동자가 임금을 인상하면 그 다음에 고용자가 다시 가격을 상승시키기 때문에 노동자의 임금 인상 크기와 고용주의 가격상승 크기가 동일해져버리기 때문이다.

칼 마르크스는 이러한 토마스 웨스턴의 주장을 다음과 같이 비판한다.

“ 임금 인상을 위한 투쟁은 오직 그 이전 가격 변화들의 궤적을 따른다. 다른 많은 요소들이 가격 변화에 영향을 미친다. 생산량, 노동 생산력, 화폐 가치, 시장 가격 변동, 산업 순환 주기의 국면들.”

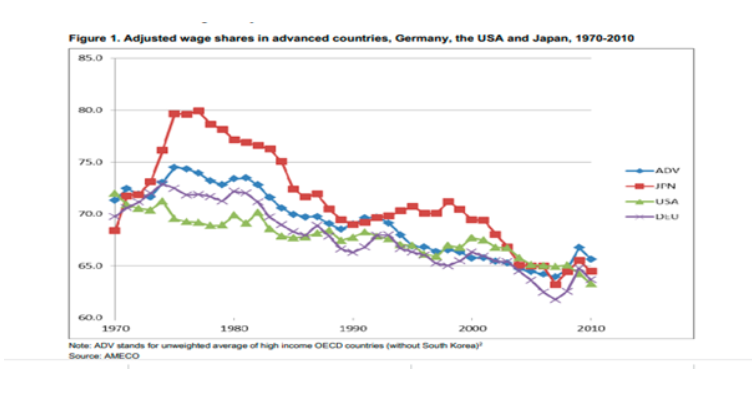

유럽 중앙은행의 해답은 노동자의 임금을 인하하라이다. 그러나 임금은 생산 몫으로서 증가하지 않았다. 코로나 기간과 후에 오히려 증가한 것은 ‘이윤 몫’이다. Profit share.

증거. 2020~2022년 사이, 미국 비-금융 분야에서 평균 가격 상승의 54%는 이윤 마진 증가에서 비롯된 것이다. 지난 40년 동안에는 11%만이 이윤 마진 증가로부터 평균 가격 상승이 발생했다 (물가 상승 원인)

(UNCTAD 보고서)

(소결) 코로나 기간과 이후에 인플레이션을 유발시킨 것은 노동자의 임금 상승이 아니라, 원자재 가격, 식량과 에너지, 이윤이다. 이러한 현실에도 불구하고, 유럽중앙은행은 이윤 가격 상승 spiral에 대해서는 침묵한다.

칼 마르크스 “노동자 임금 상승은 일반적인 이윤율 하락으로 귀결된다. 그러나 상품의 가격에는 영향을 끼치지 않는다.”

미국과 유럽 중앙은행이 걱정하는 것은 이윤의 감소이다.

이를 위한 금리 인상이라는 도구를 사용했고, 양적 완화 QE 에서 양적 경색 (QT quantitative Tightening)으로 정책을 바꿨다.

마이클 로버츠의 주장.

1. 미국 FRB 제이 포웰의 인플레 원인 분석이 오류다. 로버츠 견해는, 인플레 원인은 개인과 정부의 수요 증가와 과잉 때문이 아니라, 공급 부족으로부터 발생되었다.

식량, 에너지 공급 부족.

제조업과 기술제품에서 저생산성

코비드 이후 생산과 유통에서 경색 발생.

러시아와 우크라이나 전쟁 발발로 에너지 공급 부족.

2.

Shock therapy was the term used to describe the drastic switch from a planned publicly owned economy in the Soviet Union in 1990 to a full-blown capitalist mode of production. It was a disaster for living standards for a decade. Shock doctrine was the term used by Naomi Klein to describe the destruction of public services and the welfare state by governments from the 1980s. Now the major central banks are applying their own ‘shock therapy’ to the world economy, intent on driving up interest rates in order to control inflation, despite the growing evidence that this will lead to a global recession next year.

That’s what they say. The Federal Reserve board member Chris Waller makes it clear “I am not considering slowing or stopping rate increases due to financial stability concerns.” So even if rising interest rates begin to crack holes in financial institutions and their speculative assets, no matter. Similarly, Bundesbank chief Nagel is resolute, despite the Eurozone and Germany in particular already slipping into recession: “Interest rates must continue to rise – and significantly so”. Nagel does not just want higher interest rates; he wants the ECB to cut back on its balance sheet ie not just stop buying government bonds to keep bond yields down but actually to sell bonds, leading to rising yields.

Nagel goes on: “there is an energy price shock, the effects of which the central bank cannot change much in the short term. However, monetary policy can prevent it from leapfrogging and broadening. In this way, we are cracking the inflation dynamic and bringing the price development to our medium-term target. We have the instruments for this, especially interest rate hikes.”

All this macho talk by central bankers hides the reality. Hiking interest rates will not work in bringing inflation rates down to target levels without a major slump. That is because the current 40-year inflation rates have been mainly caused not by ‘excessive demand’ ie spending by households and governments, but ‘insufficient supply’, particularly in food and energy production, but also in wider manufacturing and tech products. Supply growth has been constrained by low productivity growth in the major economies, by the supply chain blockages in production and transport that emerged during and after the COVID slump and then accelerated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and economics sanctions imposed by Western states.

Indeed, empirical studies have confirmed that the inflation spiral has been supply-led. In a new report, the ECB found that even the rise in core inflation, which excludes the supply factors of food and energy, was driven mainly by supply constraints. “Persistent supply bottlenecks for industrial goods and input shortages, including shortages of labour due in part to the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, led to a sharp increase in inflation…Components in the HICP basket that anecdotally are strongly affected by supply disruptions and bottlenecks and components that are strongly affected by the effects of reopening following the pandemic together contributed around half (2.4 percentage points) of HICPX inflation in the euro area in August 2022.”

And in its latest Trade and Development report, UNCTAD reaches a similar conclusion. UNCTAD reckoned that every percentage point rise in the Fed’s key interest rate would lower economic output in rich countries by 0.5 percent and by 0.8 percent in poor countries over the next three years; and more drastic rises of 2 and 3 percentage points would further depress the “already stalling economic recovery” in emerging economies. In presenting the report, Richard Kozul-Wright, head of the UNCTAD team which prepared it, said: “Do you try to solve a supply-side problem with a demand-side solution? We think that’s a very dangerous approach.” Exactly.

Clearly, central banks do not know the causes of rising inflation. As Fed Chair Jay Powell put it: “We understand better now how little we understand about inflation.” But it is also an ideological approach by central bankers. All the talk from them is fear of a wage-price spiral. So their argument goes that, as workers try to compensate for price rises by negotiating higher wages, that will spark further prices and drive up inflation expectations.

This theory of inflation was summed up by Martin Wolf, the Keynesian guru of the Financial Times: “What [central bankers] have to do is prevent a wage-price spiral, which would destabilise inflation expectations. Monetary policy must be tight enough to achieve this. In other words, it must create/preserve some slack in the labour market.” So keep wages from rising and let unemployment rise. Fed chief Jay Powell reckons that the task of the Fed is “in principle …, by moderating demand, we could … get wages down and then get inflation down without having to slow the economy and have a recession and have unemployment rise materially. So there’s a path to that.”

As the governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey put it: “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”. Or take this statement from leading mainstream macro economist Jason Fulman, “When wages go up that leads prices to go up. If airline fuel or food ingredients go up in price then airlines or restaurants raise their prices. Similarly, if wages for flight attendants or servers go up then they also raise prices. This follows from basic micro & common sense.”

But both this ‘basic micro’ and ‘common sense’ are false. The theory and empirical support for wage cost-push inflation and inflation expectations theory are fallacious. Marx answered the claim that wage rises lead automatically to price rises some 160 years ago in a debate with trade unionist Thomas Weston who claimed that wage rises were self-defeating as employers would just hike prices and workers would be back to square one. Marx argued that (Value, Price and Profit) that “a struggle for a rise of wages follows only in the track of previous changes in prices”. Many other things affect price changes: “the amount of production, the productive powers of labour, the value of money, fluctuations of market prices, different phases of the industrial cycle”.

Getting wages down is the answer of the central banks. But wages are not rising as a share of output; on the contrary it is profit share that has been increasing during and since the pandemic.

And yet, according to the UNCTAD report, between 2020 and 2022 “an estimated 54 percent of the average price increase in the United States non-financial sector was attributable to higher profit margins, compared to only 11 percent in the previous 40 years.” What has been driving rising inflation has been the cost of raw materials (food and energy in particular) and rising profits, not wages. But there is no talk from central banks about a profit-price spiral.

Indeed, that was another point made by Marx in the debate with Weston: “A general rise in the rate of wages will result in a fall of the general rate of profit, but not affect the prices of commodities.” That is what really worries central bankers – a fall in profitability.

So central banks plough on with hiking interest rates and switching from quantitative easing (QE) to quantitative tightening (QT). And they are doing this simultaneously across continents. This ‘shock therapy’, first employed in the late 1970s by the then US Fed chair Paul Volcker, eventually led to a major global slump in 1980-2.

The way in which central banks are fighting inflation by simultaneously hiking interest rates is also putting massive stress on the global financial system, with actions in advanced economies affecting low-income countries.

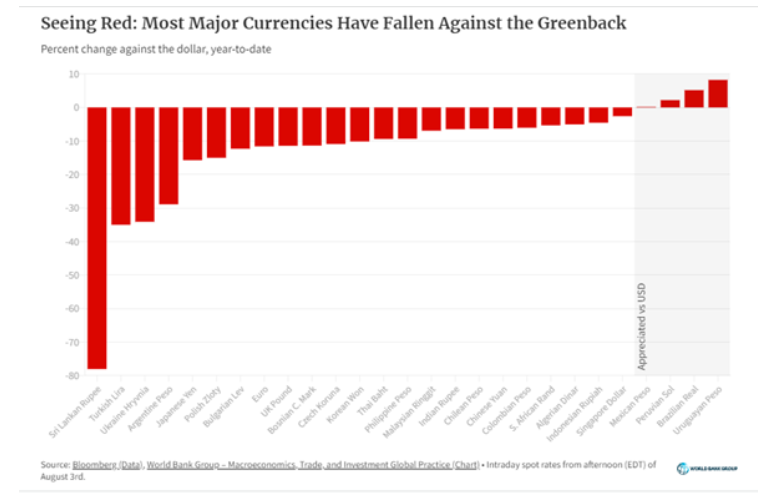

What is spreading the impact of rising interest rates on the world economy is the very strong US dollar, up around 11% since the start of the year and – for the first time in two decades – reaching parity with the euro. The dollar is strong as a safe-haven for cash from inflation, with the US interest rate up and from the impact of sanctions and war in Europe.

A huge number of major currencies have depreciated against the dollar. This is disastrous for many poor countries around the world. Many countries – especially the poorest – cannot borrow in their own currency in the amount or the maturities they desire. Lenders are unwilling to assume the risk of being paid back in these borrowers’ volatile currencies. Instead, these countries usually borrow in dollars, promising to repay their debts in dollars – no matter the exchange rate. Thus, as the dollar becomes stronger relative to other currencies, these repayments become much more expensive in terms of domestic currency.

The Institute of International Finance, recently reported that, “foreign investors have pulled funds out of emerging markets for five straight months in the longest streak of withdrawals on record.” This is crucial investment capital that is flying out of EMs towards ‘safety’.

Also as the dollar strengthens, imports become expensive (in domestic currency terms), thus forcing firms to reduce their investments or spend more on crucial imports. The threat of debt default is mounting.

All this because of the attempt of central banks to apply ‘shock therapy’ to rising global inflation. The reality is that central banks cannot control inflation rates with monetary policy, especially when it is supply-driven. Rising prices have not been driven by ‘excessive demand’ from consumers for goods and services or by companies investing heavily, or even by uncontrolled government spending. It’s not demand that is ‘excessive’, but the other side of the price equation, supply, is too weak. And there, central banks have no traction. They can hike policy interest rates as much as they deem, but it will have little effect on the supply squeeze, except to make it worse. That supply squeeze is not just due to production and transport blockages, or the war in Ukraine, but even more so to an underlying long-term decline in the productivity growth of the major economies – and behind that growth in investment and profitability.

Ironically, rising interest rates will squeeze profits. Already, forecasters have slashed their expectations for third-quarter earnings of big US companies by $34bn over the past three months, with analysts now anticipating the most feeble rise in profits since the depths of the Covid crisis. They are expecting companies listed on the S&P 500 index to post earnings-per-share growth of 2.6 per cent in the July to September quarter, compared with the same period a year earlier, according to FactSet data. That figure has fallen from 9.8 per cent at the start of July, and if accurate would mark the weakest quarter since the July to September period in 2020, when the economy was still reeling from coronavirus lockdowns.

It’s shock therapy on the global economy but not on inflation. Once the major economies slip into a slump, inflation will then fall as a result.