주장 1.인간과 다른 영장류 수면 시간 (잠자는 시간) 비교. 인간 7시간, 다른 영장류 9~15시간.

주장 2. 이사벨라 카펠리니 (Isabella Capellini) 주장은, 인간과 비교한 30개의 영장류 숫자가 너무 적다. 적어도 300 종류의 영장류와 비교가 필요하다.

주장 1.

진화론적 인류학자들 (찰스 넌 Charles Nunn, 데이비드 샘슨 David Samson) 주장.

첫번째 이유, 인류가 옛날에 나무에서 땅으로 내려와서 살게 되었을 때, 포식자(약탈자)로부터 인류를 보호하기 위해 잠을 자지 않고 깨어 있는 시간이 더 많게 되었다.

두번째 이유는 새로운 기술을 배우고 가르치면서 사회적 관계를 형성하느라 잠을 줄이게 되었다.

수면 시간이 감소할 때, 학습과 기억과 연관된 수면을 뜻하는 ' 급속 안구 운동'이 수면에서 더 큰 역할을 하게 된다.

비-REM 수면은 기억을 도와주는 역할을 하지만, 예상과 달리 인간 수면에서 적은 부분을 차지한다.

REM (rapid-eye movement 급속 눈 운동) - 학습과 기억과 연관된 수면.

급속 안구 운동.

REM 수면.

NEWS

ANTHROPOLOGY

Humans don’t get enough sleep. Just ask other primates.

People devote more time to learning, at the expense of shut-eye, researchers propose

ring-tailed lemurs

SNOOZE TIME Humans get much less sleep than expected for a primate with our biological and lifestyle characteristics, a study finds.

Most other studied primates, including ring-tailed lemurs like these, sleep about as much on average as researchers estimated they should.

ARROWSG/ISTOCKPHOTO

By Bruce Bower

MARCH 7, 2018 AT 8:00 AM

People have evolved to sleep much less than chimps, baboons or any other primate studied so far.

A large comparison of primate sleep patterns finds that most species get somewhere between nine and 15 hours of shut-eye daily, while humans average just seven.

An analysis of several lifestyle and biological factors, however, predicts people should get 9.55 hours, researchers report online February 14 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Most other primates in the study typically sleep as much as the scientists’ statistical models predict they should.

The best of Science News - direct to your inbox.

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your email inbox every Thursday.

Two long-standing features of human life have contributed to unusually short sleep times, argue evolutionary anthropologists Charles Nunn of Duke University and David Samson of the University of Toronto Mississauga.

First, when humans’ ancestors descended from the trees to sleep on the ground, individuals probably had to spend more time awake to guard against predator attacks.

진화론적 인류학자들 (찰스 넌 Charles Nunn, 데이비드 샘슨 David Samson) 주장.

첫번째 이유, 인류가 옛날에 나무에서 땅으로 내려와서 살게 되었을 때, 포식자(약탈자)로부터 인류를 보호하기 위해 잠을 자지 않고 깨어 있는 시간이 더 많게 되었다.

두번째 이유는 새로운 기술을 배우고 가르치면서 사회적 관계를 형성하느라 잠을 줄이게 되었다.

수면 시간이 감소할 때, 학습과 기억과 연관된 수면을 뜻하는 ' 급속 안구 운동'이 수면에서 더 큰 역할을 하게 된다.

비-REM 수면은 기억을 도와주는 역할을 하지만, 예상과 달리 인간 수면에서 적은 부분을 차지한다.

REM (rapid-eye movement 급속 눈 운동) - 학습과 기억과 연관된 수면.

급속 안구 운동.

REM 수면.

Second, humans have faced intense pressure to learn and teach new skills and to make social connections at the expense of sleep.

As sleep declined, rapid-eye movement, or REM — sleep linked to learning and memory (SN: 6/11/16, p. 15) — came to play an outsize role in human slumber, the researchers propose. Non-REM sleep accounts for an unexpectedly small share of human sleep, although it may also aid memory (SN: 7/12/14, p. 8), the scientists contend.

“It’s pretty surprising that non-REM sleep time is so low in humans, but something had to give as we slept less,” Nunn says.

이사벨라 카펠리니 (Isabella Capellini) 주장은, 인간과 비교한 30개의 영장류 숫자가 너무 적다. 적어도 300 종류의 영장류와 비교가 필요하다.

Humans may sleep for a surprisingly short time, but Nunn and Samson’s sample of 30 species is too small to reach any firm conclusions, says evolutionary biologist Isabella Capellini of the University of Hull in England. Estimated numbers of primate species often reach 300 or more.

Sleeper effect

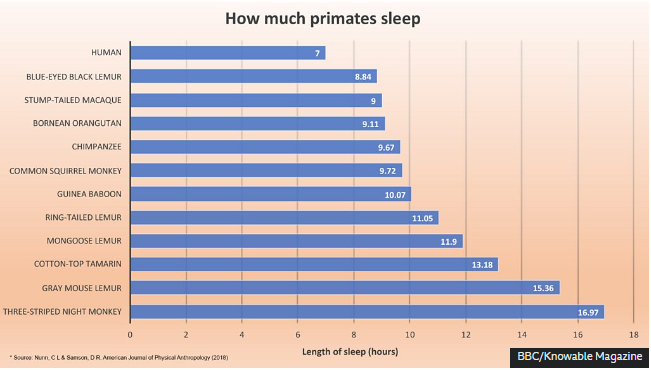

In this chart showing a subset of the data on how long primates sleep, humans stand out as snoozing the fewest hours daily, on average. They were also among three primates (dark blue bars) whose sleep times differed substantially from researchers’ predictions.

E. OTWELL

Source: C.L. Nunn and D.R. Samson/American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2018

If the findings hold up, Capellini suspects that sleeping for the most part in one major bout per day, rather than in several episodes of varying durations as some primates do, substantially lessened human sleep time.

Nunn and Samson used two statistical models to calculate expected daily amounts of sleep for each species. For 20 of those species, enough data existed to estimate expected amounts of REM and non-REM sleep.

Estimates of all sleep times relied on databases of previous primate sleep findings, largely involving captive animals wearing electrodes that measure brain activity during slumber.

To generate predicted sleep values for each primate, the researchers consulted earlier studies of links between sleep patterns and various aspects of primate biology, behavior and environments.

야행성 동물이 낮에 활동하는 동물보다 더 많이 잔다.

For instance, nocturnal animals tend to sleep more than those awake during the day.

Species traveling in small groups or inhabiting open habitats along with predators tend to sleep less.

Based on such factors, the researchers predicted humans should sleep an average of 9.55 hours each day. People today sleep an average of seven hours daily, and even less in some small-scale groups (SN: 2/18/17, p. 13).

The 36 percent shortfall between predicted and actual sleep is far greater than for any other primate in the study.

Nunn and Samson estimated that people now spend an average of 1.56 hours of snooze time in REM, about as much as the models predict should be spent in that sleep phase.

An apparent rise in the proportion of human sleep devoted to REM resulted mainly from a hefty decline in non-REM sleep, the scientists say. By their calculations, people should spend an average of 8.42 hours in non-REM sleep daily, whereas the actual figure reaches only 5.41 hours.

One other primate, South America’s common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), sleeps less than predicted. Common marmosets sleep an average of 9.5 hours and also exhibit less non-REM sleep than expected. One species sleeps more than predicted:

South America’s nocturnal three-striped night monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) catches nearly 17 hours of shut-eye every day. Why these species’ sleep patterns don’t match up with expectations is unclear, Nunn says. Neither monkey departs from predicted sleep patterns to the extent that humans do.

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at feedback@sciencenews.org | Reprints FAQ

A version of this article appears in the March 31, 2018 issue of Science News.

CITATIONS

C.L. Nunn and D.R. Samson. Sleep in a comparative context: Investigating how human sleep differs from sleep in other primates. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Published online February 14, 2018. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23427.

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/humans-primates-sleep-evolution

Why humans get less sleep than other primates

24 May 2022

S

By Elizabeth Preston

Features correspondent

NurPhoto/Getty Images It is widely believed that our hectic modern lives cause us to sleep poorly, but our sleeplessness might have routes in our evolutionary past (Credit: NurPhoto/Getty Images)NurPhoto/Getty Images

It is widely believed that our hectic modern lives cause us to sleep poorly, but our sleeplessness might have routes in our evolutionary past (Credit: NurPhoto/Getty Images)

The amount of time we spend awake and asleep compared to our relatives among the apes, monkeys and lemurs may have played a key role in our evolution.

On dry nights, the San hunter-gatherers of Namibia often sleep under the stars. They have no electric lights or new Netflix releases keeping them awake. Yet when they rise in the morning, they haven't gotten any more hours of sleep than a typical city-dweller in North America or Europe who stayed up doom-scrolling on their smartphone.

Research has shown that people in non-industrial societies – the closest thing to the kind of setting our species evolved in – average less than seven hours a night, says evolutionary anthropologist David Samson at the University of Toronto Mississauga. That's surprising when you consider our closest animal relatives. Humans sleep less than any ape, monkey or lemur that scientists have studied.

Chimpanzees sleep around 9.5 hours out of every 24. Cotton-top tamarins sleep around 13. Three-striped night monkeys are technically nocturnal, though really, they're hardly ever awake — they sleep for 17 hours a day.

Samson calls this discrepancy the human sleep paradox.

"How is this possible, that we're sleeping the least out of any primate?" he says. Sleep is known to be important for our memory, immune function and other aspects of health. A predictive model of primate sleep based on factors such as body mass, brain size and diet concluded that humans ought to sleep about 9.5 hours out of every 24, not seven. "Something weird is going on," Samson says.

Research by Samson and others in primates and non-industrial human populations has revealed the various ways that human sleep is unusual. We spend fewer hours asleep than our nearest relatives, and more of our night in the phase of sleep known as rapid eye movement, or REM. The reasons for our strange sleep habits are still up for debate but can likely be found in the story of how we became human.

BBC/Knowable Magazine Graph comparing primate sleep (Credit: BBC/Knowable Magazine)BBC/Knowable Magazine

Millions of years ago, our ancestors lived, and probably slept, in trees. Today's chimpanzees and other great apes still sleep in temporary tree beds or platforms. They bend or break branches to create a bowl shape, which they may line with leafy twigs. (Apes such as gorillas sometimes also build beds on the ground.)

Our ancestors transitioned out of the trees to live on the ground, and at some point started sleeping there too. This meant giving up all the perks of arboreal sleep, including relative safety from predators like lions.

Fossils of our ancestors don't reveal how well-rested they were. So, to learn about how ancient humans slept, anthropologists study the best proxy they have: contemporary non-industrial societies.

"It's an amazing honour and opportunity to work with these communities," says Samson, who has worked with the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania, as well as with various groups in Madagascar, Guatemala and elsewhere. Study participants generally wear a device called an Actiwatch, which is similar to a Fitbit with an added light sensor, to record their sleep patterns.

Gandhi Yetish, a human evolutionary ecologist and anthropologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, has also spent time with the Hadza, as well as the Tsimane in Bolivia and the San in Namibia. In a 2015 paper, he assessed sleep across all three groups and found that they averaged between only 5.7 and 7.1 hours.

It makes sense that the threat of predators may have led humans to sleep less than tree-living primates

Humans, then, seem to have evolved to need less sleep than our primate relatives. Samson showed in a 2018 analysis that we did this by lopping off non-REM time. REM is the sleep phase most associated with vivid dreaming. That means, assuming other primates dream similarly, we may spend a larger proportion of our night dreaming than they do. We're also flexible about when we get those hours of shut-eye. (Read about the lost medieval habit of biphasic sleep.)

To tie together the story of how human sleep evolved, Samson laid out what he calls his social sleep hypothesis in the 2021 Annual Review of Anthropology. He thinks the evolution of human sleep is a story about safety – specifically, safety in numbers. Brief, flexibly timed REM-dense sleep likely evolved because of the threat of predation when humans began sleeping on the ground, Samson says. And he thinks another key to sleeping safely on land was snoozing in a group.

"We should think of early human camps and bands as like a snail's shell," he says. Groups of humans may have shared simple shelters. A fire might have kept people warm and bugs away. Some group members could sleep while others kept watch.

"Within the safety of this social shell, you could come back and catch a nap at any time," Samson imagines. (He and Yetish differ, however, on the prevalence of naps in today's non-industrial groups. Samson reports frequent napping among the Hadza and a population in Madagascar. Yetish says that, based on his own experiences in the field, napping is infrequent.)

Samson also thinks these sleep shells would have facilitated our ancient ancestors' journey out of Africa and into colder climates. In this way, he sees sleep as a crucial subplot in the story of human evolution.

It makes sense that the threat of predators may have led humans to sleep less than tree-living primates, says Isabella Capellini, an evolutionary ecologist at Queen's University Belfast in Northern Ireland. In a 2008 study, she and her colleagues found that mammals at greater risk of predation sleep less, on average.

Alamy Although chimpanzees are our closest living primate relative, their sleep patterns are remarkably different from our own (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

But Capellini isn't sure that human sleep is as different from that of other primates as it seems. She points out that existing data about sleep in primates come from captive animals. "We still don't know much about how animals sleep in the wild," she says.

In a zoo or laboratory, animals might sleep less than is natural, because of stress. Or they might sleep more, Capellini says, "just because animals are that bored". And the standard laboratory conditions — 12 hours of light, 12 hours of dark — might not match what an animal experiences in nature throughout the year.

Neuroscientist Niels Rattenborg, who studies bird sleep at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany, agrees that Samson's narrative about the evolution of human sleep is interesting. But, he says, "I think it depends a lot on whether we have measured sleep in other primates accurately."

And there's reason to suspect we haven't. In a 2008 study, Rattenborg and colleagues attached electroencephalography (EEG) devices to three wild sloths and found that the animals slept about 9.5 hours per day. An earlier study of captive sloths, on the other hand, had recorded nearly 16 daily hours of sleep.

Having data from more wild animals would help sleep researchers. "But it's technically challenging to do this," Rattenborg says. "Although sloths were compliant with the procedure, I have a feeling primates would spend a lot of time trying to take the equipment off."

고대 인류들은 밤에 불을 피워놓고, 잠을 자지 않고, 정보와 문화를 교환했다. (대체 인간이란 무엇인가?)

Ancient humans may have traded some hours of sleep for sharing information and culture around a dwindling fire

If scientists had a clearer picture of primate sleep in the wild, it might turn out that human sleep isn't as exceptionally short as it seems. "Every time there is a claim that humans are special about something, once we start having more data, we realise they're not that special," Capellini says.

Yetish, who studies sleep in small-scale societies, has collaborated with Samson on research. "I do think that social sleep, as he describes it, is a solution to the problem of maintaining safety at night," Yetish says. However, he adds, "I don't think it's the only solution."

He notes that the Tsimane sometimes have walls on their houses, for example, which would provide some safety without a human lookout. And Yetish has had people in the groups he studies tell him in the morning exactly which animals they heard during the night. Sounds wake most people at night, offering another possible layer of protection.

Sleeping in groups, predator threats or not, is also a natural extension of the way that people in small-scale societies live during the day, Yetish says. "In my opinion, people are almost never alone in these types of communities."

Yetish describes a typical evening with the Tsimane: after spending the day working on various tasks, a group comes together around a fire while food is cooked. They share a meal, then linger by the fire in the dark. Children and mothers gradually move away to sleep, while others stay awake, talking and telling stories.

Jorge Fernández/Getty Images Sharing stories around a fire after dark is common in many non-industrial societies (Credit: Jorge Fernández/Getty Images)Jorge Fernández/Getty Images

Sharing stories around a fire after dark is common in many non-industrial societies (Credit: Jorge Fernández/Getty Images)

And so Yetish suggests that ancient humans may have traded some hours of sleep for sharing information and culture around a dwindling fire. "You've suddenly made these darkness hours quite productive," he says. Our ancestors may have compressed their sleep into a shorter period because they had more important things to do in the evenings than rest.

How much we sleep is a different question, of course, from how much we wish we slept. Samson and others asked Hadza study participants how they felt about their own sleep. Out of 37 people, 35 said they slept "just enough," the team reported in 2017. The average amount they slept in that study was about 6.25 hours a night. But they awoke frequently, needing more than 9 hours in bed to get those 6.25 hours of shut-eye.

By contrast, a 2016 study of almost 500 people in Chicago found they spent nearly all of their time in bed actually asleep, and got at least as much total sleep as the Hadza. Yet almost 87% of respondents in a 2020 survey of US adults said that on at least one day per week, they didn't feel rested.

Why not? Samson and Yetish say our sleep problems may have to do with stress or out-of-whack circadian rhythms. Or maybe we're missing the crowd we evolved to sleep with, Samson says. When we struggle to get sleep, we could be experiencing a mismatch between how we evolved and how we live now. "Basically we're isolated, and this might be influencing our sleep," he says.

A better understanding of how human sleep evolved could help people rest better, Samson says, or help them feel better about the rest they already get.

"A lot of people in the global North and the West like to problematise their sleep," he says. But maybe insomnia, for example, is really hypervigilance — an evolutionary superpower. "Likely that was really adaptive when our ancestors were sleeping in the savannah."

Yetish says that studying sleep in small-scale societies has "completely" changed his own perspective.

"There's a lot of conscious effort and attention put on sleep in the West that is not the same in these environments," he says. "People are not trying to sleep a certain amount. They just sleep."

* This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, and is republished under a Creative Commons licence.

--

반응형