1. 팔레스타인과 이스라엘 전쟁의 역사적 기원, 1차 세계대전 당시 영국의 지배전략

팔레스타인과 이스라엘의 전쟁 기원은 팔레스타인 지역을 포함한 아랍지역에서 영국과 프랑스의 지배전략에서 비롯되었다. 자국의 이익을 위해 영국은 팔레스타인 사람들과 유태인인들에게 서로 상충되는 '약속'을 따로따로 해줬고, 이것이 향후 팔레스타인과 이스라엘의 갈등과 전쟁의 원인이 되었다.

2. 영국은 팔레스타인을 포함한 아랍지역에서 오토만 제국 (현재 튀르키예,터어키, 오스만 투르크 제국)을 물리치기 위해 아랍인들의 힘이 필요했다.

** 참고. 당시 오토만 제국과 연맹한 나라는 독일, 오스트리아-헝가리, 불가리아였다. 이 4대 동맹국들과 초창기에 싸운 연합국 주요나라가 영국, 프랑스, 러시아, 세르비아 등이다. (1917년 러시아 혁명으로 러시아 제국 연합국에서 이탈, 미국 캐나다 등은 이후 참전 결정)

1915~1916년 맥마흔-후세인 편지 교환. The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence,14 July 1915 - 10 March 1916,

영국은 아랍인들에게 독일과 동맹을 맺은 오토만 제국과 싸워 줄 것을 요구하고, 그 대신 오토만 제국을 패배시킨 후 아랍인들에게 독립국가를 약속했다. 팔레스타인 지역에 사는 아랍-팔레스타인들도 영국의 약속을 믿음.

3. 영국은 팔레스타인 지역에 유태인의 국가를 수립하겠다고 유태인에게 약속한 배경,1차 세계대전과 전쟁비용 마련.

1917년 11월 전쟁 비용을 마련하고자, 영국은 팔레스타인 지역에 유태인 '가정, 집'을 지어주겠다고 약속했다. 전쟁비용이 시급했던 영국은 아서 밸푸어(Balfour)를 시켜 유태인 금융부호 로스차일드(Rothschild) 가문에 긴급구호를 요청하고,그 대신 영국계-유태인 로스차일드에게 팔레스타인 지역에 '유태인 집 Home' 수립을 약속했다. 전 세계에 흩어져 사는 유태인들 중, '시온주의자들은 '유태인 집'을 유태인 국가로 이해했다.

4. 영국과 프랑스의 비밀협약. 1916년 5월 8일. 사이크스-피코 비밀협약.

프랑스와 영국의 아랍지역 분할 통치안.

1) 영국 (아일랜드 포함)의 직접 지배 지역 - 이라크와 이란 사이 오렌지 색깔

2) 영국의 영향권. 이라크, 요르단 (석유 발굴)

3) 프랑스 직접 지배 지역 - 레바논, 시리아 위쪽, 튀르키예 사이.

4) 프랑스 영향권 - 시리아

5) 러시아 제국 - 시리아 위쪽 튀르키예

6) 국제 사회 공통 지배 - 팔레스타인 (하이파 포함된 땅)

1차 세계 대전 기간에는 영국이 자기 필요에 따라, 오토만 제국을 물리치기 위해서 아랍인들에게 '아랍 독립'을 약속하고, 오토만 제국 타도에 나설 것을 요구했다. 동시에 전쟁 비용을 유태인 부호들에게 받아내기 위해서 팔레스타인 지역에 '유태인 국가 (시온주의 노선과 일치)'를 수립해주겠다고 약속했다.

그러나 실제로는 영국과 프랑스는 팔레스타인 지역을 포함한 이 중동지역을 분할 통치할 계획을 수립했다. 그것이 사이크스-피코 비밀협약이다.

Map of showing Eastern Turkey in Asia, Syria and Western Persia, and areas of control and influence agreed between

the British and the French. Royal Geographical Society, 1910-15.

Signed by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, 8 May 1916

좌. 마크 사이크스, 우 프랑소와 피코 ( Mark Sykes, François Georges-Picot)

(1차 세계대전, 오토만 제국, 불가리아, 오스트리아-헝가리 제국, 독일 등 4대 동맹국가 vs 연합국가 영국, 프랑스, 러시아, 이탈리아 세르비아 등)

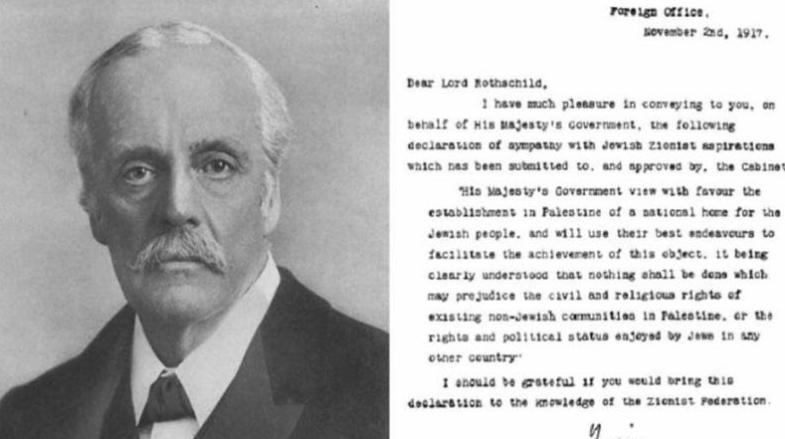

5. 밸푸어 (밸포어) 선언. 아서 밸푸어 선언 (1917년 11월 2일) 영국 외무부 서기 아서 밸푸어가 팔레스타인에서 유태인 민족의 '집 (가정)'을 부여하겠다는 선언이다. (national home 민족의 집 =독립된 나라를 의미) 밸푸어가 당시 영국-유태인 공동체의 대표인 리오넬 로스차일드에게 보내는 편지에서, 팔레스타인 지역에서 '유태인 독립국가' 약속을 한 것이다.

Balfour Declaration, (November 2, 1917), statement of British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” It was made in a letter from Arthur James Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild (of Tring), a leader of the Anglo-Jewish community.

Though the precise meaning of the correspondence has been disputed, its statements were generally contradictory to both the Sykes-Picot Agreement (a secret convention between Britain and France) and the Ḥusayn-McMahon correspondence (an exchange of letters between the British high commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, and Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, then emir of Mecca), which in turn contradicted one another (see Palestine, World War I and after).

The Balfour Declaration, issued through the continued efforts of Chaim Weizmann and Nahum Sokolow, Zionist leaders in London, fell short of the expectations of the Zionists, who had asked for the reconstitution of Palestine as “the” Jewish national home.

The declaration specifically stipulated that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” The document, however, said nothing of the political or national rights of these communities and did not refer to them by name. Nevertheless, the declaration aroused enthusiastic hopes among Zionists and seemed the fulfillment of the aims of the World Zionist Organization (see Zionism).

The British government hoped that the declaration would rally Jewish opinion, especially in the United States, to the side of the Allied powers against the Central Powers during World War I (1914–18). They hoped also that the settlement in Palestine of a pro-British Jewish population might help to protect the approaches to the Suez Canal in neighbouring Egypt and thus ensure a vital communication route to British colonial possessions in India.

The Balfour Declaration was endorsed by the principal Allied powers and was included in the British mandate over Palestine, formally approved by the newly created League of Nations on July 24, 1922.

In May 1939 the British government altered its policy in a White Paper recommending a limit of 75,000 further immigrants and an end to immigration by 1944, unless the resident Palestinian Arabs of the region consented to further immigration.

Zionists condemned the new policy, accusing Britain of favouring the Arabs. This point was made moot by the outbreak of World War II (1939–45) and the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

------------

Hussein-McMahon correspondence, series of letters exchanged in 1915–16, during World War I, between Hussein ibn Ali, emir of Mecca, and Sir Henry McMahon, the British high commissioner in Egypt.

In general terms, the correspondence effectively traded British support of an independent Arab state for Arab assistance in opposing the Ottoman Empire. It was later contradicted by the incompatible terms of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, secretly concluded between Britain and France in May 1916, and Britain’s Balfour Declaration of 1917.

A member of the Hashemite clan (a line descended from the Prophet Muhammad), Hussein ibn Ali was appointed as the emir of Mecca in 1908.

Although the Ottoman Empire officially administered the region, the position of emir—which carried the responsibilities of overseeing the safekeeping of the holy sites at Mecca and Medina and managing the hajj (pilgrimage)—was one of prestige and provided a measure of autonomy.

Hussein’s appointment came at a time of general uncertainty in the Ottoman Empire. Local autonomy had been increasingly undermined by reforms that centralized administration of the empire in Istanbul, now governed by the Young Turks.

At the same time, an Arabic literary renaissance (known as the Nahda) was flourishing, exciting notions of Arab nationalism and a desire for greater autonomy among the empire’s Arab subjects.

Hussein, though an Ottoman appointee, mistrusted the Young Turk government, which had indicated a preference to rule the holy places directly.

Seeking both to address the calls for Arab autonomy and to salvage his own, Hussein reached out to the British for support. Although Britain initially declined an opportunity to cooperate with Hussein against the Turks, following the entry of the Ottomans into World War I, the British perceived strategic value in partnering with a Muslim ally.

In July 1915 Hussein took the opportunity to send a letter to McMahon detailing the conditions under which he would consider a partnership with the British. Hussein, who claimed to represent all Arabs, effectively sought independence for the entirety of the Arabic-speaking lands to the east of Egypt.

McMahon, however, insisted that certain areas falling within the French sphere of influence, such as the districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and land lying west of Damascus (Homs, Hama, and Aleppo—i.e., modern Lebanon), would not be included and emphasized that British interests in Baghdad and Basra would require special consideration.

Hussein disagreed with the exception of the French-claimed areas and stipulated that certain rules had to govern British activity in Baghdad and Basra, terms to which McMahon did not give his assent. In the end, the matters were set aside for discussion at a later date. Ultimately, the highly ambiguous correspondence was in no way a formal treaty, and disagreements on several points persisted unresolved.

In addition to disagreements within the letters themselves, conflicts of interest were magnified by secret negotiations between Britain and France that culminated in 1916 in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which effectively re-portioned between them the entirety of the Ottoman Empire, and later by the Balfour Declaration, which assured British support for the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. Hussein, however, apparently sufficiently convinced of British support, announced the launch of the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans in June 1916. Although the revolt was relatively minor, with British backing, the Arab forces succeeded in dominating the Hejaz region of the Arabian Peninsula, as well as Aqabah and Damascus.

In late 1918 Hussein’s son Faisal entered Damascus and began to set up an administration there in accordance, he believed, with his father’s understanding with the British. In March 1920 Greater Syria (Syria along with Transjordan, Palestine, and Lebanon) was proclaimed independent from rule by foreign powers and was declared a constitutional monarchy with Faisal as king, a move that directly challenged French interests there. At the Conference of San Remo in April 1920, it was France’s claims to Syria that were formalized, and Syria was placed under French mandate. The decision (and Faisal’s capitulation to the terms of the agreement) sparked violent unrest that was met in July by French forces, which imposed an easy defeat and forced Faisal into exile.

The Hussein-McMahon correspondence remained a point of heated contention thereafter, particularly as it related to Palestine, which the British claimed was included in the land to be set aside for the French. Although it is uncertain precisely what Hussein expected or even what exactly McMahon had offered, it is certain that the Arabs achieved far less from the ambiguous arrangement than they had anticipated.

출처. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Arthur-James-Balfour-1st-earl-of-Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st earl of Balfour | Prime Minister, UK Statesman, Philosopher

Arthur James Balfour, 1st earl of Balfour, British statesman who maintained a position of power in the British Conservative Party for 50 years. He was prime minister from 1902 to 1905, and, as foreign secretary from 1916 to 1919, he is perhaps best remembe

www.britannica.com