영국 bbc 보도. 로라 비커 기자.

가디언지 보도.

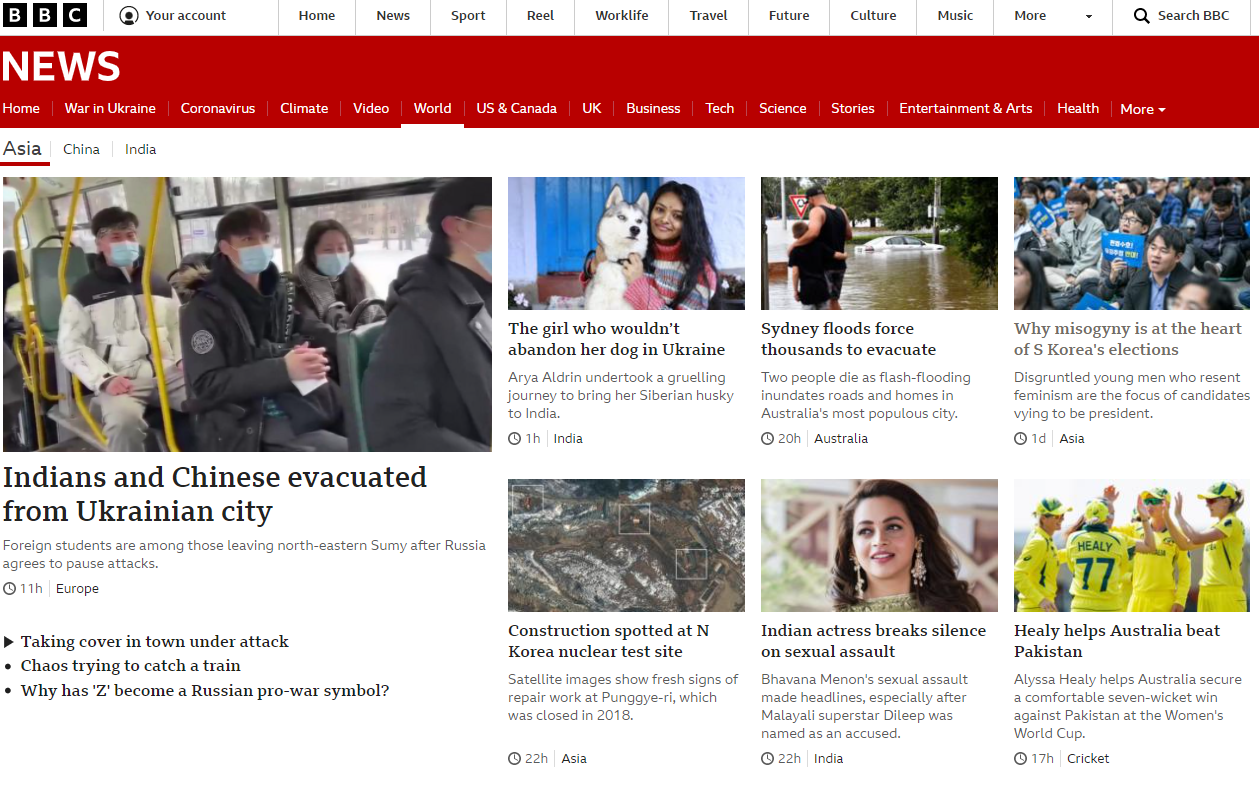

한국 대선, 왜 '여성혐오'가 중심으로 떠올랐는가?

영국 bbc 보도. 로라 비커 기자. 가디언지 보도. 한국 대선, 왜 '여성혐오'가 중심으로 떠올랐는가? Why misogyny is at the heart of South Korea's presidential elections-By Laura Bicker-BBC News, Seoul misogyny 미써지니. 여성에 대한 편견, 여성을 싫어하는 감정. the feeling of hating or strongly disliking women, or being prejudiced against

1) 요점. 20대 남자들의 90%가 반-페미니즘이거나 지지자가 아니다.

2) 한국 현실. 한국의 여성권리는 선진국에서 최하위 기록임.

그런데 왜 젊은 남성들은 화가 나 있는 것인가? 젊은 남성들의 인식 상태.

-20대 남성이 해석하는 페미니즘이란, ‘성 평등’을 위한 투쟁으로 인식하지 않는다. 20대 남성들은 페미니즘에 짜증을 내고, 남성에 대한 역차별, 남자들의 일자리와 기회를 빼앗아간다고 생각함.

3) 한국내 여성 성폭력 반대 시위 주제들.

여성들의 ‘몰카’ 반대 투쟁. ‘미투 운동’

4) 정치권에서 젠더 주제가 폭발한 배경.

한국에서 젠더 정치는 지뢰밭이다.

실 생활에서 유권자 관심사항. 주택가격 폭등, 정체된 경제성장, 청년실업

(*그러나 기성 정치권에서 권력형 성범죄 발생함.)

민주당 서울시장 부산시장 충남도지사 성폭력 사건.

5) 윤석열과 국민의힘이 어떻게 젠더 정치를 역이용했는가?

윤석열 국힘 후보는 여가부 폐지 공약 (the ministry of Gender Equality and Family)

여가부 예산은 전체 0.2%. 그 중 3% 미만이 성평등 예산임.

6) 남성의 문제제기들. 군복무와 구직에 대한 정치적 해법은 제시하지 않은 국민의힘.

젊은 남성층 79%가 역차별을 경험하고 있다고 답변.

30세 이전 18개월 군복무. 이에 대한 사회적 보상이 없다.

윤석열. 구조적 성차별이 없다.

그러나 여성 임금은 남성의 67.7% (노동-고용부 발표)

대기업 임원의 경우, 여성이 차지하는 비율은 5%.

성폭력에 대한 처벌 수준이 낮음. 41.4%는 집행유예, 30%는 벌금만 냄. 20%만이 실형.

7) 선거 막바지에 윤석열 태도 약간 달라짐. “성폭력과 전쟁 선포”

이재명은 ‘페미니즘’ 선언.

그 배경에는 여성 유권자 표가 중요하기 때문.

8) 현실에서 느끼는 20대 젊은 여성들의 우려.

페미니스트에 대한 온라인 공격 심각. ‘페미니스트들은 다 죽어야 한다’ 등.

유투버 BJ Jammi 재미 자살 사망. “남성을 싫어하는 페미니스트”라는 낙인.

여자들도 군대가라는 해법이 아니다.

20대 여성의 좌절감 문제.

구세대 남성의 여성혐오보다 더 무서운 것은 동년배 남성의 여성혐오 의식이다. 미래에는 바뀌겠지 그런 희망이라도 가지는데, 동년배 남성들이 갖는 여성혐오 의식 때문에, 여성들이 느끼는 좌절감은 더 크다.

Why misogyny is at the heart of South Korea's presidential elections-By Laura Bicker-BBC News, Seoul

misogyny 미써지니. 여성에 대한 편견, 여성을 싫어하는 감정.

the feeling of hating or strongly disliking women, or being prejudiced against them

South Korean men and a few women chant slogans during a protest against #MeToo

Hundreds of South Korean men organized an Anti-#MeToo rally in 2018

Park Min-young, 29, spends most of his day talking to angry young men in Seoul.

His fingers relentlessly tap the keyboard as he replies to dozens of their messages at his desk in the centre of a busy campaign office for one of South Korea's main presidential candidates, Yoon Suk-yeol.

"Nearly 90% of men in their twenties are anti-feminist or do not support feminism," he tells me.

South Korea has one of the worst women's rights records in the developed world. And yet it is disgruntled young men who have been the focus of this country's presidential election.

Many do not see feminism as a fight for equality. Instead they resent it and view it as a form of reverse discrimination, a movement to take away their jobs and their opportunities.

It is a disparaging development for the tens of thousands of young women who took to the streets of Seoul in 2018 to shout "Me Too" after several high profile criminal cases involving sexual harassment and spy camera crimes known as "molka".

But now that cry is being drowned out by men shouting "Me First".

The country's gender politics is a minefield the country's next leader will have to navigate - if they can first win the battle to get into office.

The contest

Conservative candidate Mr Yoon and his liberal rival Lee Jae-myung are neck and neck in a contest to become the next leader of Asia's fourth largest economy.

Voters' top concerns are skyrocketing house prices, stagnant economic growth, and stubborn youth unemployment.

Neither have any experience as legislators in the National Assembly which is a first in South Korea's democratic history.

And neither appear to have a strong female voting base. Both parties have been accused of misogyny.

Yoon Suk-yeol (R) and Lee Jae-myung (L) are both neck and neck in the contest

Mr Lee's ruling Democratic Party has seen a number of high-profile sexual harassment scandals, with the mayor of Busan sent to prison for sexual assault.

Mr Yoon, of the People's Power Party, has made abolishing the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family a central pledge of his campaign.

The ministry largely provides family-based services, education, and social welfare for children and spends around 0.2% of the nation's annual budget - less than 3% of which goes towards the promotion of equality for women. But Yoon knows this move will be popular among a key demographic - young men.

A survey last year by a local newspaper found that 79% of young men in South Korea feel "seriously discriminated against" because of their gender.

As I walk with Min-young to a cafe to meet some of these young men, he tells me that "feminism has been going in the wrong direction".

He says many men he's spoken to feel "let down", adding that he believes it is "necessary to pacify, to convince and to appease them first".

These men claim that they are not trying to drown out the voices of women, but simply to amplify the voices of young men.

One of their biggest issues is that all men must serve 18 months in the military before they are 30 years old.

"There is no reward. Just sacrifice," says Min-young. "The military is a huge fear for Korean men… that they are forced to go to this place they can't resist for one year and six months. And to have to compete with women after returning from the military.

"This country's patriarchy system also gives women the burden of child rearing, [which means the] men have the burden [of proving] their economic capabilities."

The men I'm introduced to do stump speeches for Mr Yoon who has declared that there is no systemic gender discrimination in South Korea.

The facts do not support that argument.

The average monthly wage for a South Korean woman in 2020 was 67.7% of that of a man, according to the Ministry of Employment and Labour. This is the biggest wage gap among developed countries.

The continuing trauma of S Korea's spy cam victims

Why women in Korea are reclaiming their short hair

#MeToo takes hold in South Korea

Feminists living in fear

Women make up only 5% of boards in South Korea's corporate world.

When it comes to sexual crimes against women, sentencing has been traditionally low. In the last 10 years 41.4% of perpetrators were given probation, around 30% were given a fine.

That means just over 28% of those found guilty were sent to prison.

The pains of young women however, have been largely ignored in this election. Until now.

A writer for the Korea Herald, Yim Hyun-su noted in an article at the weekend that both candidates have refreshed their appeal to women on social media.

Mr Lee has pledged to tackle discrimination and Mr Yoon declared a "war on sex crimes".

In such a close race, it seems they have realised that young women may now hold the deciding votes.

But it will be a tough sell for those who fight for equality in South Korea. They are now scared to reveal their identities.

We spoke to a group of two men and two women who wanted to face away from our cameras. We have given them fake names to protect them.

The interviewees say identifying yourself as a feminist has unimaginable consequences

"As a feminist to reveal your face and speak out has such unimaginable consequences," says Ji-eun, a YouTuber who is in her early 20s.

"When we upload a video on feminism on our YouTube channel, male communities organise an attack and say things like 'You are a feminist? Feminists should all die.'

I have seen these comments for myself. This malicious online bullying can have terrible consequences.

In January, YouTuber BJ Jammi ended her life having endured years of abuse after trolls accused her of being a "man-hating feminist".

But amidst the deepening divisions, there is understanding too. Especially when it comes to men having to serve in the military.

"I sympathise with that and the fact that only males have to go is an unjust structure," said Ji-eun.

"But the responsibility for this should be on the government and the history of this divided country - but to say to women in their twenties 'Well, you don't go to the military' is very unjust."

This anti-feminist backlash will be a challenge for whoever steps into the presidential office known as the Blue House.

South Korea is at a cultural crossroads. It has a tech-savvy young generation who do not share the patriarchal views of their parents or their grandparents. Both genders will likely keep pushing and are looking at those in charge to bring real change.

But Ji-eun still feels hopeless about her future.

"If the hate was coming from the older generation, I might hope that at some point when my generation is in power or in places of importance in society, it could change. But the anti-feminists and those who don't care about women's rights and spewing hate are in my generation.

"It's hard to picture a bright future even far ahead."

Justin McCurry in Tokyo

Mon 7 Mar 2022 02.58 GMT

The identity of South Korea’s next leader will be determined this week by the economy, housing prices and incomes, but the road to the presidential Blue House will also be dotted with the wreckage of the country’s poisonous gender politics.

The successor to Moon Jae-in, who is restricted by law to a single five-year term, will not be able to ignore the fallout from a campaign defined by the culture war being waged in the world’s 10th-biggest economy.

On one side, a feminist movement that led the Me Too movement in Asia; on the other, young men whose resistance to the modest gains made by South Korean women has been exploited by the two main candidates.

South Korea’s presidential candidates face balancing act amid rising anti-China sentiment

Read more

In 2018, women took to the streets in record numbers to call for government action against an epidemic of molka – the use of spy cams to secretly film women, often in public toilets – and helped bring down several public figures, including a candidate for the presidency, for sexual misconduct.

A year later, they helped overturn a decades-old ban on abortion, and shone a light into the darkest corners of an entrenched culture of male chauvinism, unequal pay and the expectation that their careers will end when they have children.

Despite the global success of its pop music and TV dramas, South Korea continues to perform poorly in international comparisons of women’s rights.

The 2021 World Economic Forum global gender gap report ranks it 102 out of 156 countries in an index that examines jobs, education, health and political representation.

South Korea has by far the largest gender pay gap among OECD countries, at about 32%, while women account for just over 19% of MPs in the national assembly. Only 5.2% of Korean conglomerates’ board members are female, and experts say the country’s record-low birthrate proves how difficult it is for its women to combine careers with family life.

Women have responded by challenging social norms, from refusing to wear bras and publicly destroying their makeup collections to vowing never to marry or have children or, in some cases, have sex with men.

Five years after its first female president, Park Geun-hye, went on trial on corruption charges, South Korea’s election campaign has brought the anti-feminist backlash into sharp focus.

Online “men’s rights” groups have condemned hiring quotas, while calls to abolish the ministry of gender equality and family – created in 2001 – have been seized on by the frontrunner.

Swoman rides a bike in seoul

Happy alone: the young South Koreans embracing single life

Read more

The anti-feminist movement’s list of grievances includes the weighty subject of military service exemptions but often finds expression in vicious personal attacks on prominent women. They include An San, the triple Olympic archery gold medalist, who was abused during last summer’s Tokyo 2020 Games simply for having short hair.

Last year, South Korea’s biggest convenience store pulled ads for sausages after a a so-called men’s rights group complained that a promotional image – a hand gesture commonly used to indicate something small – had once been used by a feminist group to exploit male anxiety over penis size.

The misogyny contagion spread to the country’s politics late last year, when Cho Dong-youn, a military specialist, was forced to resign just three days after she had been appointed co-chair of the ruling Democratic party’s election committee.

Cho, a Harvard graduate with successful military and academic careers behind her, stepped down after a YouTube channel and broadcaster questioned her suitability for office. Her crime: having a child out of wedlock during her first marriage.

As the campaign enters its final stages, the conservative People Power party candidate, Yoon Suk-yeol, and his ruling Democratic party rival, Lee Jae-myung, have been accused of pandering to sexism to win the votes of young men who regard women’s advancement as a threat to their financial security, amid a bleak job market and rising living costs.

Presidential candidate Lee Jae-myung, left, of the ruling Democratic Party and Yoon Suk-Yeol of the main opposition People Power Party

Presidential candidate Lee Jae-myung, left, of the ruling Democratic Party and Yoon Suk-Yeol of the main opposition People Power Party Photograph: AP

Many resent having to do 18 months of military service, a requirement for all able-bodied Korean men aged 18-28, while women are exempt. Hong Eun-pyo, who runs an anti-feminist YouTube channel, has tried to justify the gender pay gap, insisting that men work longer hours and do more difficult jobs. “If [women] want to reach as high as their male peers and be paid the same wages, they should keep working and not get pregnant,” he said.

Yoon, a former prosecutor general, has accused the gender equality ministry of treating men like “potential sex criminals” and has promised to introduce tougher penalties for false claims of sexual assault – a step campaigners say will deter even more women from coming forward.

In addition, scrapping the gender ministry could weaken women’s rights and “take a toll on democracy”, said Chung Hyun-back, an academic who served as gender equality minister under Moon.

Yoon, 61, is said to be heavily influenced by his party chairman, Lee Jun-seok, a 36-year-old Harvard graduate and “men’s rights” advocate who has criticised hiring targets for women and other female-friendly policies as “reverse discrimination”, and described feminist politics as “blowfish poison”.

Even Lee, the potential liberal successor to self-proclaimed feminist Moon, has said he opposes “discrimination” against men, and cancelled an interview with a media outlet because of its supposed feminist leanings. Although he opposes Yoon’s plans to abolish the gender equality ministry, he wants to drop the word “women” from its official Korean-language title.

By the weekend, Yoon had established a small lead over Lee, after Ahn Cheol-soo, a minor party candidate, withdrew from the race and threw his support behind the People Power candidate. According to a Realmeter poll published on Wednesday, 46.3% of respondents said they would vote for Yoon, with 43.1% backing Lee.

While the two frontrunners go out of their way to avoid offending young male voters, women say the election has plunged South Korea back into the dark ages. “We are being treated like we don’t even have voting rights,” said Hong Hee-jin, a 27-year-old office worker in Seoul.

“Politicians are taking the easy path. Instead of coming up with real policies to solve problems facing young people, they are fanning gender conflicts, telling men in their 20s that their difficulties are all down to women receiving too many benefits.”

Agencies contributed reporting

'진보정당_리더십 > 2022 대선' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 국민의힘 윤석열, '정권교체' 이외에 5년 집권 '보수정권' 계획표 부실했다. 정권교체 여론보다 13%~15% 나 뒤처진 윤석열 후보 지지율. (0) | 2022.03.09 |

|---|---|

| 자료. 87년 이후, 역대 대통령 지지율 변화. 하락 이유들. 노태우, 김영삼, 김대중, 노무현, 이명박, 박근혜, 문재인. (0) | 2022.03.09 |

| [한겨레] 2022년 ‘기후 대선’은 왜 실패했는가 (0) | 2022.03.09 |

| [경실련] 후보자등록 때 아파트 재산 시세보다 윤석열 13억, 이재명 8억 낮게 신고 (0) | 2022.03.08 |

| 사라진 '노인'·엇갈리는 여론조사...민심 제대로 읽었을까?2025년 10명 가운데 2명 이상이 65세 이상 노인 (0) | 2022.03.08 |

| 여론조사 발표 금지제도 폐지해야 한다. 폐해가 더 심각. (0) | 2022.03.07 |

| [여론조사] 넥스트 리서치. 윤석열 39.9%, 이재명 34.1%, 안철수 10.3%, 심상정 2.1% (0) | 2022.03.07 |